At the very beginning, during the early days of confusion and uncertainty, we moved through international airports with an anxious vigilance. My spouse and I had carefully loaded our daughters’ small backpacks with extra masks and disinfecting wipes. In the lounge, we sanitized nearby surfaces and listened to workers gossip about the virus and worry about their jobs. In the Boeing 787, we swabbed the armrests and folding tables before taking off for a nine-hour trip. The normally packed flight had empty rows between passengers. The fear of close quarters, not yet government mandates, made for apprehensive “social distances.” Then, just before we touched down halfway around the world, Ottawa clamped down on international travel.

The pandemic had not been part of our plan to spend two years on a remote island in the Tsushima Strait, midway between Japan and Korea, so that we could give our kids the cultural and educational experience of a lifetime. Serendipitously, the isolation of Ikijima largely shielded us from the rising case counts, fumbling government responses, straining health care systems, and irritating anti-mask rallies that we saw happening elsewhere. For an entire year, our island, just seventeen kilometres long and fourteen kilometres wide, had but three outbreaks, each lasting only a few weeks and resulting in a hundred or so cases. There was a single unfortunate death linked to the virus. We were grateful for this relatively safe place, where my girls quickly settled into the daily routine of walking to their elementary school with the neighbourhood kids and running through the bamboo forests with their new friends after class.

You do what it takes to get back home.

M.G.C.

These months weren’t without heartbreak, though. We were excited to be in Japan, in part, because we all looked forward to spending time with my mother-in-law, who was nearing the end of her years-long battle with cancer. But shortly after we arrived, my father-in-law, worried about beds filling up with novel coronavirus patients, took her to the hospital —“just for the weekend.” Mere days after we landed and before she could see her granddaughters in person one last time, she passed. The closest we came was standing outside the hospital.

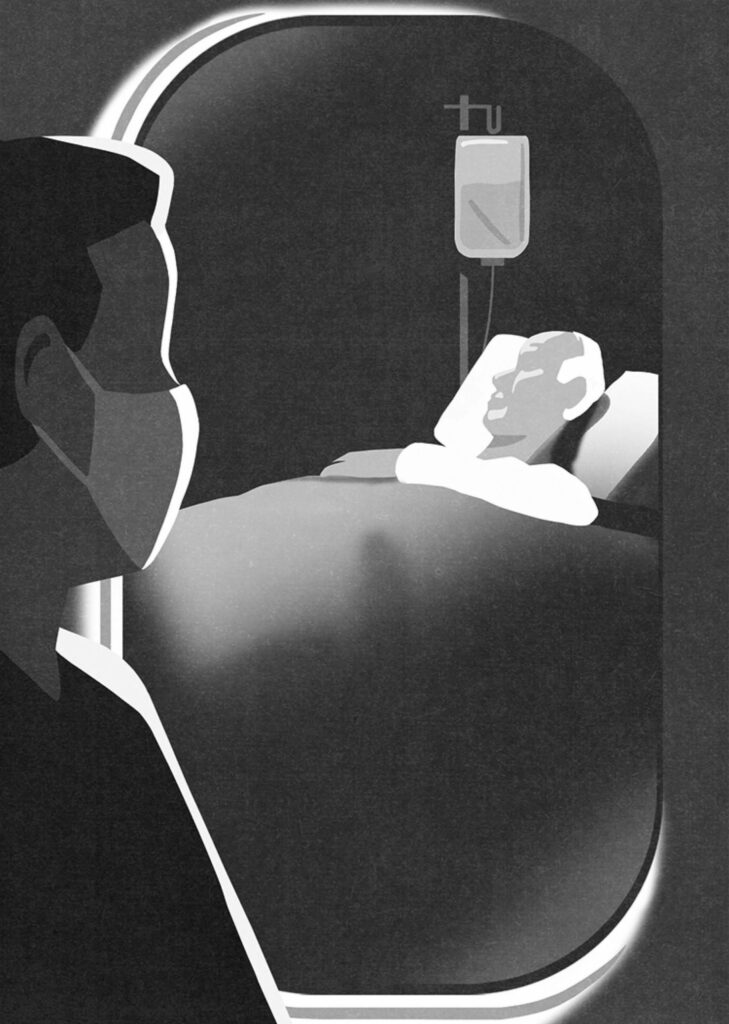

So when my father was diagnosed with an aggressive lung cancer months later, I knew right away that we couldn’t risk something like that again. Information was scarce, time seemed short, and decisions needed making. But when the cancer call comes again, you do what it takes to get back home.

Our liberal globalized system is designed for the free flow of people. Of course, those bodies are the vectors that viruses use to put the whole enterprise at risk. Restricting the movement of the virus means restricting the movement of people, preventing them from doing almost everything they want or need to do, even the simple human act of seeing a dying parent.

We knew that in a short but very long year, the status quo had been completely upended by those preventive efforts. To feel confident that we would not be turned away at any point of our journey, we had to navigate layers of overburdened and siloed bureaucracy. It took no end of researching, deciphering the changing rules, scheduling, double-checking, following up by email and phone, and adjusting almost daily. Then, a week before we were to leave Japan, international shipping to Canada was suspended; we would be allowed to take only what we could carry onto the plane. So before we completed our spit tests and headed to the airport, we had to give away nearly everything we had brought with us and everything we had acquired.

But then, thankfully, we were back.

The international terminal at the Vancouver airport has a long, brightly lit hall behind glass where arriving passengers can wave to waiting loved ones. Looming over the scene are two large statues, carved in red cedar, with arms outstretched and palms facing upward. These are the Welcome Figures by the Nuu-chah-nulth artist Joe David.

I have been on both sides of this glass many times, and the place tends to fill me with warmly tinted memories. This time, however, the tone was different. The once familiar space had been converted into a cardboard maze, with that stretch of glass covered in public health signs and instructions. Lines and arrows guided us to COVID testing booths, before we were shuffled along by masked staff in latex gloves to another waiting area, where we stayed until we caught our ride to a nearby “government authorized accommodation.” Somehow, I did not even see the Welcome Figures.

Although we had made it into the country, we still faced countless hurdles before we could see my father. First, we needed a response to our “request for exemption for compassionate reasons,” which would allow us to leave quarantine so that we could visit the hospital. At the airport, a public health worker kindly made some calls to help expedite the process. After even more calls and emails, I was forced to file the application all over. It felt as if we were being failed by every process along the way — that after well over a year, the system still had not adapted to the realities of a global crisis.

After our second round of tests came back negative, we were able to leave the YVR vicinity and head four and a half hours east to a rented “isolation house” in Kelowna. After a few days, we were allowed to travel by private car to the hospital — but nowhere else. When I saw my father for the first time since before the pandemic, it looked as if he had aged a decade. His salt-and-pepper hair was now nearly all salt, and his thin legs barely held him up as he leaned on his IV stand and breathed with the assistance of a respirator. When he saw his grandchildren, who against so many odds had crossed an ocean to be with him, he had tears in his eyes. Everyone smiled.

Things have changed in recent weeks, but under the federal quarantine restrictions that were then in place, travellers were to isolate for fourteen days upon arrival. My father passed away on our eleventh day home. Although I am deeply saddened to have sat at his side, stroking the back of his hand as he drew his last strained breaths, I almost consider myself one of the lucky ones. So many families in similar situations, separated by artificial walls hastily thrown up to protect public health, have not been as successful. Many have got lost in regulatory labyrinths or have not had the resources to make such a journey. Some have simply been overwhelmed by the stress of imagining a loved one dying alone in a hospital room far away. For me the pandemic has been an obstacle, something to work around. And I’m grateful for my success, however bittersweet.

Chad Kohalyk divides his time between Canada and Japan.