Successful use of intelligence has been an important resource for states in the making of grand diplomatic and military policy. In the Second World War, the ULTRA secret permitted the Allies to decrypt German military communications, thus providing them with a strategic leg-up. Intelligence failures, like Air India or 9/11, have caused massive political embarrassment.

Yet day-to-day intelligence activities often serve less exalted purposes. It is a dirty but not very well-kept secret that all too often spying is just pornography for states, allowing them to engage in prurient games that fall short of actual conflicts with material consequences. John Le Carré’s Cold War novels capture this reality with cynical precision. The frissons of deception and betrayal grip readers but mean next to nothing in the bigger picture of global politics.

As even free speech liberals are uneasily aware, pornography cannot always be contained within the limits of private indulgence but may blur into harmful impacts on real, vulnerable, people. Routine espionage and counter-espionage carried on by rival bureaucracies may seem an expensive but relatively harmless pastime. When intelligence assets are redeployed for more active uses—what the Americans refer to as covert actions such as sabotage, assassination, regime destabilization—the results are not at all harmless. Innocent people die and ugly impacts work their way through entire societies.

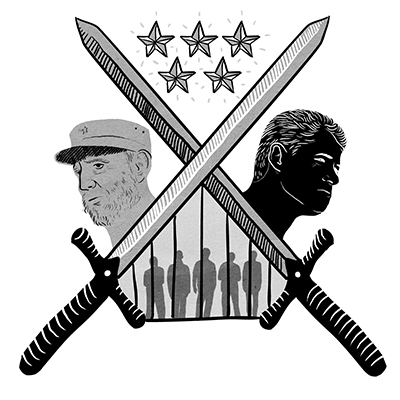

Stephen Kimber’s What Lies Across the Water: The Real Story of the Cuban Five focuses on the nexus of the United States, communist Cuba 145 kilometres off the Florida coast, the anti-communist exiles in Florida and the rival intelligence services of the two countries. This is, as Kimber shows, a poisonous, even deadly nexus.

Oliva Mew

Since the Cuban revolution in 1959, hostile relations between the United States and Fidel and Raoul Castro’s Cuba, beginning as a small subset of Cold War competition with the former Soviet Union, have survived the end of the Cold War and the demise of the Soviet state. Intelligence power has been the favoured instrument of competition, but relations have always hovered in a twilight zone where clandestine “peacetime” conflict continually threatens to erupt into actual violence. Less than three years after the victorious guerillas arrived in Havana, an inexperienced young U.S. president was drawn by anti-communist Cuban exiles into the humiliating fiasco of the Bay of Pigs invasion. In 1962 the world came within one minute of nuclear midnight in the Cuban missile crisis. Throughout, a draconian American sanctions regime has imposed severe economic damage on the lives of Cubans (matching the damage caused by heavy-handed Soviet controls by the Castro government).

These were all public matters. We now know a great deal about covert actions initiated by the White House and the Central Intelligence Agency, enlisting everyone from professional spies and bloodthirsty exiles to Las Vegas mobsters and shady mercenaries in plots to kill Fidel Castro and destabilize the regime by any means possible, however dubious in terms of law, ethics or even common sense. And then there is the Cuban exile community in South Florida: uncompromisingly committed to the overthrow of the Cuban regime; fiercely vengeful toward its leaders and supporters; and effective as a lobby that holds much of the American media, Congress and successive presidents in its grip, confining American Cuban policy within the narrow tunnel vision of the exiles.

With regard to Cuba (or later Saddam Hussein’s Iraq) Americans might better have eschewed ideological solidarity and instead heeded the long-ago advice of Machiavelli about how dangerous it is to trust to the representation of political exiles. “So extreme is their desire to return to their homes,” he wrote, “that they naturally believe many things that are not true, and add many others on purpose … They will fill you with hopes to that degree that if you attempt to act upon them you … will engage in an undertaking that will involve you in ruin.”

The hardline exiles have never been content merely to voice their opposition to the Castro brothers and all their works. Clandestine gangster-like groups have carried out armed and violent actions against the Cuban homeland, sometimes in shadowy collaboration with elements of the American secret state, at other times benefitting from official American silences accompanied by friendly winks and nudges. These actions have included bombs in Cuban public places and a horrific act of air piracy: in 1976 a Cuban Air DC-8 flight from Barbados to Jamaica was brought down by terrorist bombs, with 78 fatalities, the deadliest terrorist airline attack in the western hemisphere to that date. The conspirators, with links to the CIA, were identified but have escaped criminal convictions. Even in the age of the “global war on terror,” the U.S. has deployed a remarkably shameless set of double standards, bitterly denouncing terrorism in all its forms and pledging to bring its perpetrators remorselessly to justice, while turning a benignly blind eye, or worse, to terrorism carried out in the name of anti-communism—even though the Cold War is a fading memory.

The starting point of Kimber’s examination of this rat’s nest of violence and deception is the 1998 arrest and subsequent conviction of five Cuban “spies” in Florida: Gerardo Hernández, Ramón Labañino, Antonio Guerrero, Fernando González and René González. These “illegal” undercover agents of Cuban intelligence ranged in age at the time of their arrest from 33 to 42 years. Some had Cuban wives (at least one of whom was left for some years in ignorance of the reasons for her husband’s sudden departure from Cuba); one had picked up an American girlfriend who knew nothing about his real identity. All were given lengthy prison sentences and all, with the exception of René González, who was released on parole in 2011, remain behind bars today but have hopes of release in the future. Gerardo Hernández, now 48, sentenced to two life terms plus 15 years [!], has no hope of ever seeing the light of day. There was brief optimism about a more liberal American stance when Barack Obama assumed the presidency, but Obama showed no interest in reconsidering the prisoners’ situation.

Kimber carried on a lengthy correspondence with los muchachos, as they are affectionately known in Cuba, and found them, despite their condition, polite and helpful in assisting his efforts to reconstruct their tangled story.

In America, these men have been viewed as evidence of the Castro regime’s malign intent toward democracy, and as proof of the effective work of the Federal Bureau of Investigation in protecting America from foreign agents. In Cuba they are Los Cinco, the “Cuban Five,” proof of the hypocritical mendacity of the American regime in promoting terrorism against the Cuban people.

These two views are obviously incommensurate with one another, if not in outright contradiction. How to square this circle? Without going so far as simply to echo Cuban propaganda—which Kimber does not—he makes a strong case that wherever the truth finally lies in this wilderness of mirrors, it will look rather more like the Cuban than the American version of reality.

Although the Cubans were convicted of conspiring to commit espionage against the U.S., evidence was never presented of any harm to America or American interests that had resulted or was likely to result from their activities on American soil. In fact, their mission from the Cuban intelligence service that had dispatched them to Florida was not to spy upon the United States at all but to infiltrate and attempt to neutralize anti-Castro groups organizing attacks against Cuba. They had been quite successful in penetrating the targeted organizations. Despite the exiles’ ferocious anti-communism, they proved inept in identifying Castro’s agents planted among them. This is not so surprising: enthusiastic self-deluders, exile groups are easy prey for penetration, an early example being that of the anti-Bolshevik groups opposing the 1917 Revolution from outside Russia that were thoroughly penetrated and manipulated by agents of Lenin’s Cheka.

The Cubans were less successful, however, in neutralizing the exile groups that carried on planting bombs in Havana, one of which killed a Canadian visitor. This is where Kimber’s story becomes more interesting—and more opaque. Cuban intelligence actually made efforts to warn the Americans about the threats posed by the exile groups. With the assistance of the celebrated Nobel Prize–winning Colombian novelist Gabriel García Márquez, who carried a secret message from Fidel Castro to U.S. president Bill Clinton, the information gathered by the Los Cinco network on the exiles’ operations was brought to the attention of American officials. A secret Cuban-American meeting was even held in which information was exchanged and Cuban intelligence apparently left with the impression that some form of cooperation might be arranged between the long-time antagonists to contain the threat of terrorist attacks.

What the Cuban undercover agents in Florida did not know was that they had fallen under close FBI counter-espionage surveillance. Their arrest and subsequent convictions and lengthy prison sentences, amid maximum media publicity about smashing an extensive Cuban spy network, put paid to any future Cuban-American cooperation to stamp out freelance terrorism launched from Florida. What is unclear is the precise role of the FBI and American authorities in these developments. Were the Americans simply duplicitous in their dealings with the Cubans, always intending to exploit the matter for anti-Castro propaganda while continuing to covertly support exile terrorism? Or is it rather a matter of the American state and its agencies, including the FBI, being less than monolithic, the left hand not knowing what the right hand is doing? Either interpretation is possible. Kimber offers evidence to back each hypothesis, while sensibly noting that too much is murky and hidden to pass final judgement.

Kimber has done an admirable job of tracking down as much information on this tangled affair as is likely to see the light of day for some time to come. Interviews with participants seem to have been difficult at times. High political stakes and the shark-like ruthlessness of the exile activists appear to have spooked many who have brushed up against this story over the years. Kimber refers to the curious indifference shown by mainstream North American publishers to his publishing project. It has finally appeared under the imprimatur of Fernwood Publishing, a small but energetic left-wing publisher in Halifax and Winnipeg. Kimber and Fernwood are to be commended for getting out a story that needs to be told.

Admirable as the author’s intentions may be, the book is not without flaws. Kimber confides that his original intention to write a novel set in Cuba was sideswiped by this stranger-than-fiction tale. The book perhaps strives too hard to retain novelistic elements. It proceeds as a series of short, almost cinematic snapshots in which various characters, villains and more-or-less heroes are introduced and then set aside for later. The effect is rather like one of those British TV detective dramas that start with a series of seemingly unconnected vignettes that gradually resolve into one interconnected narrative. In this case, however, there are too many characters who flit by too quickly to impress their identity clearly with the reader. Instead of coming together, by the end the narrative becomes if anything even more formless and perplexing. Much of this is attributable to the mysterious nature of the story itself and the contested status of the facts. But one wonders: might a more analytic approach have shed more light?

In any event, if Kimber’s narrative remains unresolved, one could say precisely the same about the state of Cuban-American relations more than six decades after the revolutionary fighters burst onto the streets of Havana on New Year’s Day 1959. Since then no fewer than eleven American presidents have grappled unsuccessfully with the spectre of a communist state 145 kilometres off the American coast, including a close brush with global nuclear Armageddon in 1962. The combined efforts of American, Cuban and Soviet intelligence agencies, as well as the rogue anti-communist exile state-within-a-state in South Florida, have succeeded only in roiling and muddying the waters yet further, not to speak of causing considerable collateral human damage along the way. What Lies Across the Water is both a commentary on and a symptom of this never-ending story.

Reg Whitaker is the co-author of Secret Service: Political Policing in Canada from the Fenians to Fortress America (University of Toronto Press, 2012).