Public interest in accounts of quaint Mennonite life is matched only by public interest in stories of rebellious Mennonite adolescence. Thankfully, Carla Funk’s Mennonite Valley Girl: A Wayward Coming of Age refuses to pander to either appetite. Funk, who served as Victoria’s inaugural poet laureate from 2006 to 2008, has recently turned to narrative non-fiction, and she writes with an unpretentious, almost effortless style. Largely set in the logging town of Vanderhoof, in the British Columbia Interior, in the early 1980s, her personal essays are sturdy, stand-alone pieces that hang on “that hinge of adolescence,” where she recalls herself “easing out of the awkward, oily surge of puberty and into the cocky cynicism of youth.”

Readers who are led astray by this book’s title — those looking, perhaps, for a salacious, bonnet-busting tell‑all — will be disappointed. (Spoiler: The author never dons, and so never doffs, a bonnet. Her people aren’t that kind of Mennonite.) But those who loved Funk’s place-based Every Scrap and Wonder: A Small-Town Childhood, from 2019, will especially like these deeply textured reminiscences. Less auto-ethnographic than that memoir, which follows the cycle of the seasons as it narrates the life of Funk’s family and town throughout her childhood, Mennonite Valley Girl offers a greater interior perspective on her teenage self.

Funk writes with the force and uncanny memory of someone deeply indebted to a particular place and era — even as she spent years itching to leave. Like teenagers kicking stones outside Food Marts the aimless world over, she recalls being “hungry for nothing in particular, hungry for everything they didn’t sell.” Moving from essay to essay, we follow Funk as she wades waist-deep through her Evangelical Mennonite community, past the constriction of her devout mother’s kitchen-bound red apron, and beyond the open shop doors that let out a whiff of her coarse father’s “trucker-cologne”: sweat and smoke and grease and the sweet tinge of Pepsi mixed with rye. All the while, the adolescent Funk hovers on the margins of waywardness, wishing she and her friends “were cooler, and better at being bad.” Aside from one errant gasoline-fuelled driveway fire, she’s recalling not a flaming artistic rebellion but a smouldering, youthful awareness of difference and in-betweenness in a valley town. Which is precisely what makes her a writer of such observational detail and nuance.

The cover of Mennonite Valley Girl shows a cross-stitched title and a pair of torn jean shorts, but the clothing belongs to someone other than Funk: perhaps Gina, who shows up at summer camp in red stilettos and shocks the other girls with a sailor’s mouth and a sex appeal that’s nearly impossible to resist. Or perhaps the shorts belong to Ruth, a friend who spends a discomfiting summer evening with a boy on Funk’s front lawn, while Funk, her naïveté stripped away, observes from her perch on the kitchen counter: “I kept watching. While he clutched Ruth, and their bodies rocked across the blankets, I turned the faucet on and off, on and off, letting the cold water run over my toes, on and off, until my feet felt numb.”

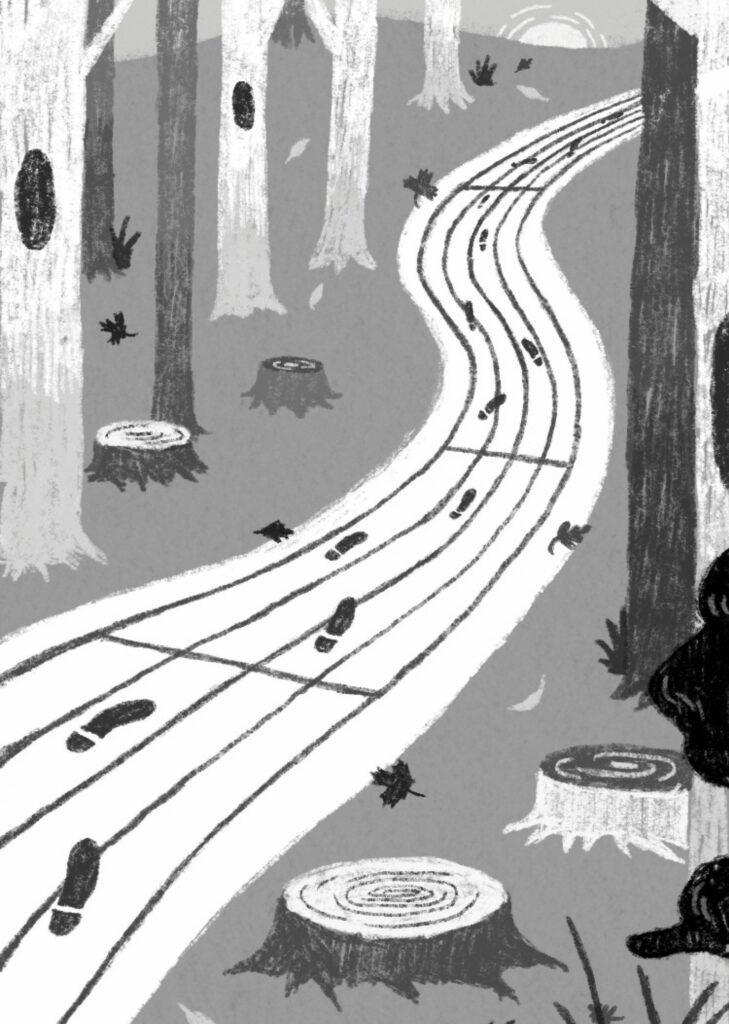

Into some semblance of a path.

Nicole Iu

Funk recalls Gina, Ruth, and other women young and old so that she might plumb the depths of her own wayward heart. Each time Gina “missed the mark,” Funk explains, “I couldn’t help but feel the gleam of my own goodness brighten.” But by the end of camp, it’s this same girl who “punched a hole clean through the pattern I thought I understood, the gospel I’d always believed.”

Funk’s skill as a poet is especially evident in the diegetic musicality of her essays. The sounds of her youth — snatched phrases from old hymns (“morning by morning”) and selected lyrics from contemporary worship music (“It only takes a spark to get a fire going”) — are set within prose sentences that move in the other direction, away from institutional religion. This music is soon replaced by her father’s country radio stations and the gyrating rhythm of Billy Idol’s “Mony Mony” in the darkened high school gymnasium.

What is exciting about essayistic memoirs right now is the way writers are increasingly playing with the varied forms that creative non-fiction can take. Funk is no exception. In the essay “Baby, Baby,” for example, she braids her babysitting travails in among the cautionary tales of pregnancy she witnessed. With “Drive,” she interweaves the language of car and trucker culture with stories of the road — both the freedom it offers and the gendered strictures of who gets to sit behind the wheel. Funk is at her most experimental in “Is This Love? — A Quiz,” where she pivots to the second person and poses a series of multiple-choice questions about long-ago crushes and an ill-conceived secret engagement: “But not yet, the boy explains. Obviously, not right now, he says. Eventually. One day. Maybe in a few years. Four, or maybe five. When you’re both done university. But he loves you, he insists, as he tugs the ring from the box’s velvet slit. You offer: . . .” The four possible responses — funny and self-deprecating and hyper-specific — reveal as much as they conceal. There is, after all, no answer key.

With “The News from Here,” Funk explains how her speedy typing landed her an internship at the local paper, and it’s here that the various impressions of her youth are brought more clearly into focus: no longer a young woman’s coming of age but a story that describes the apprenticeship of the writer. By the end, we find a novice reporter, a valedictorian, a maker of tall tales.

In her penultimate essay, Funk spends the summer after high school helping to clear trails outside of town. Though she nearly severs her own leg with a chainsaw, she soon finds her rhythm with a Pulaski axe and ends the piece by remarking how “with every downward swing of the blade, another root sprang loose, another step on the path opened up.” The metaphor — slashing and writing her way out of Vanderhoof — may be obvious, but it nonetheless embodies great truth. We can’t make good sense of the places that shape our youth without first hacking at, exposing, and re-forming our roots into some semblance of a path. Ultimately, Mennonite Valley Girl is a kind of retroactive trail clearing. Funk shows us how we might make sense in arrears, how we can story-stitch our adult selves together in a world so intent on flattening difference and eradicating the local.

Geoff Martin was nominated for a Pushcart Prize for “Baked Clay,” an essay about Mennonite and Black land histories in rural Ontario.