In an era when wars are intractable and dispiriting to follow, there are increasing dangers for the relatively small band of foreign correspondents who cover them. The dedication of such reporters can be hard to fathom, as year after year they bear witness in the most violent corners of the globe. Somehow, they override their own fears to function through an unimaginable string of conflicts; many will cover a dozen or so throughout a career, some well over twenty. It’s a unique occupation where the stress is brutal, the casualties high. Inner scars can develop from seeing so much mass suffering while manoeuvring around the possibility of being killed, wounded, imprisoned, or kidnapped oneself. But if reporters don’t pry into what are usually other people’s struggles, how can readers and viewers penetrate such darkness?

War reporting has long been dominated by men, yet some of the most determined journalists have been women, who have had to break through sexist barriers just to reach the conflict zones, where they are at even higher risk than their male counterparts. Women have been among the best at the job, and their pedigree is longer than we often assume.

With extraordinary resilience.

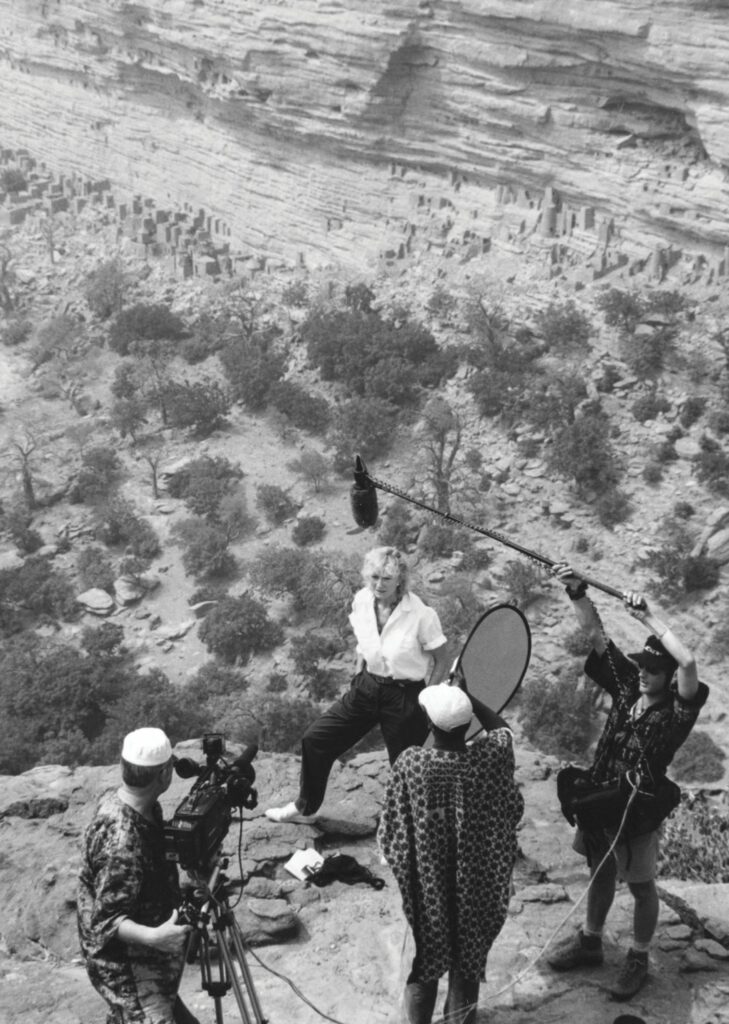

Courtesy of Hilary Brown

In the early 1700s, Europe saw its first celebrity female correspondent, Anne-Marguerite du Noyer, from France, who was eagerly read across the continent for her ability to make sense of the War of the Spanish Succession. In the late 1840s, publications in the United States sent a female, Jane Cazneau, on horseback to cover the Mexican-American War, and another, Margaret Fuller, to report on the revolution in Rome. During the First World War, a remarkable Canadian, Florence MacLeod Harper, covered the Eastern Front for a U.S. magazine and wrote eyewitness accounts of the Russian Revolution that historians continue to value. Still others pulled off hair-raising breakthroughs: a British woman made it to the Western Front disguised as a common soldier, while an American twice crossed German lines posing as a refugee.

From the Spanish Civil War in the 1930s down to the recent fall of Kabul, women have regularly been reporting on hostilities. Martha Gellhorn, for example, covered most major conflicts over an astonishing sixty-year career, even scooping her first husband, Ernest Hemingway, on the D‑Day landings (they soon divorced). She lived to nearly ninety, still fifteen years shy of her fellow legend Clare Hollingsworth, who scooped the entire British media in 1939 as Germany invaded Poland. Hollingsworth survived wars around the world for decades and lived to 105.

Inevitably, some of the best, no matter how experienced, don’t survive. The acclaimed Times of London correspondent Marie Colvin lost an eye in Sri Lanka’s civil war and suffered PTSD, but she remained determined “to bear witness” and returned to cover the Syrian fighting by motorcycle. She was killed by shelling in 2012. Those who seek such work clearly don’t fall into it by accident. They self-select; they are drawn toward adventurous careers and fortified by a tolerance far beyond the human norm for handling trauma.

With her new memoir, War Tourist, the journalist Hilary Brown offers fascinating insights into the making of a daring career.

Brown was celebrated during the Vietnam War as one of the first female foreign correspondents on television, in what’s seen as “the first televised war.” Over sixty news personnel had been killed covering the conflict when the U.S. network ABC flew her into the steaming heat of Saigon in spring 1975, just as America’s involvement in South Vietnam was coming to an end.

At twenty-nine, Brown was nearly six feet tall, blond, and fit. She had covered only short conflicts before and had less than two years’ experience with the network. She was “so wet behind the ears I was dripping,” she writes.

Most mortals would quail at going anywhere near such a dangerous situation: a long war bleeding into utter chaos, where fire from either side might get you. For Brown, the opportunity answered her long-held dream to “cover wars, revolution, general mayhem!” She impressed audiences and producers with the crisp authority of her on‑cameras, as she followed torrents of refugees fleeing the fighting and the panicked crumbling of Southern units. Caught in the firefight around the last defended bridge in Saigon, she had to roll her way under the crossfire so she could sign off while lying down. She then barely made it through the bug-out bedlam at the U.S. Embassy and onto one of the last Marine helicopters airlifting refugees to offshore carriers. After that, she watched as escaping Vietnamese choppers were pushed overboard for lack of space. One of Brown’s cool closing lines from that day —“This seems to be the last chapter in the history of American involvement in Vietnam”— so caught the sentiment of utter defeat that it was included in the 1978 film The Deer Hunter.

Emotional scars, including guilt over not being able to rescue civilians who had helped her, haunted Brown for years. But ahead lay network praise, a posting to the prestigious Paris bureau, and well-paid media prominence. Even more important for her, there were other chances to feed something of an addiction for ultimate challenges.

Having long been aware of Brown as a media force — as we both dropped in and out of wars — I wanted to know if War Tourist would reveal how life had nudged her toward so dangerous a path. Although we covered some of the same conflicts, I met her only once, briefly, in a CBC studio in Toronto in the 1980s. I remember her as a veteran, with considerable presence, who’d seen everything, and I thought how lucky I was never to have faced her as a competitor in the field.

It’s only in the past twenty years that major strides have been made in analyzing the psychology of war reporters like Brown and how so much exposure to violence and bloodshed affects their emotional well-being. It’s a growing body of study driven mainly by the psychiatrist Anthony Feinstein, of the University of Toronto and Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre.

After facing considerable resistance within the media early on, Feinstein has now conducted hundreds of interviews with those who’ve practised war journalism. He has examined the effects and the treatments of PTSD, while his more recent studies have looked at so-called moral injury, or the blow to one’s sense of ethics, which brings feelings of guilt, say, for not having done more to aid civilians trapped in war zones.

Feinstein’s work reveals a sharper picture of those who report from conflict zones. Their motives range from a yearning to “sit in the front row of history” and resistance to nine-to-five living to a belief that witnessing is critical in so violent a world. Some dislike the precariousness, but they are driven by determination to cast light on human suffering. Regardless of their motivations, most correspondents share an extraordinary resilience.

What’s striking in War Tourist is Brown’s love of risk and trust in luck, even from her early days as a gifted student in Ontario and Switzerland. In her mid-teens, for example, she and her parents drove around Europe in the school holidays, and a “heart-stopping experience” on a narrow cliffside road brought about an epiphany. ”I loved it!” she recalls. “That was when I first learned that you never feel more alive . . . than when you think you may soon be dead.” Another moment occurred at Western University, when a disastrous love affair with a “Svengali” professor twice her age threatened to bring campus-wide scandal, after his car flipped into a ditch while they were on a secret getaway to Boston. To her amazement, she suffered few scratches and no scandal: ”I was lucky, lucky, lucky. Lucky without deserving it. And as it turned out, I was lucky again, and again, and again in my long and mainly happy life.”

Even by the standards of the ’60s, Brown led a dazzling free-spirited life after graduation. Despite having no sailing experience, she decided to go yacht racing, joining an all-male crew as gourmet galley chef and soon becoming the captain’s lover. On an early job in an Ottawa newsroom, she livened up the annual Press Gallery Dinner with a memorable striptease. She moved easily between media jobs in London and Paris, where her magnetic personality led to a wide circle of friends, entry into high society, and an impressive string of brainy lovers. She describes the era as “the Golden Age of Sex” and writes, “We didn’t need professions of undying love or hints of marriage to jump into the sack.”

In Montreal, Brown landed a job as one of the first female TV news hosts in Canada and became a close friend of Leonard Cohen. When she grew restless, she moved on to the New York art scene as a publicist for the Guggenheim Museum, escorting the likes of Jackie Kennedy through exhibitions. But Brown also craved risk, and after a trek through Nepal’s Himalayan foothills, she decided to drop into the raging India-Pakistan War of 1971 to find freelance work. At her first news briefing, a phalanx of bored correspondents who had been in the country for days advanced on her. It was a moment of fate: leading the rush was the Hollywood-handsome John Bierman, a famed BBC correspondent and future historian. He was soon the great love of Brown’s life and her husband for thirty years, before his death from cancer in 2006.

Brown and Bierman both covered conflicts, sometimes together, and between assignments they led a glittering life, with a seaside villa in Cyprus, postings to top capitals, and a busy social calendar that included John le Carré, godfather to their one child, John. And though she appreciated the idyllic moments, she could not resist those big stories when wars raged.

Brown tells of being almost torn apart by an anti-Western mob in revolutionary Iran; of hiking through no man’s land to investigate a possible massacre in El Salvador; and of dodging rocket and sniper fire in Sarajevo. She recounts civil wars in Africa and conflicts in Afghanistan and Iraq. She does not exaggerate, she admits mistakes, and she downplays her skills as compared with those of today’s women reporters.

Despite its jaunty title, War Tourist is not a frivolous work but, in part, a lament about haunting guilt —“that I’m just a war tourist in a flak jacket, documenting human misery, and then moving on.” And though Brown suffered a devastating three-year depression in the ’90s, she does not cite trauma on the job as a cause. Instead, she blames a severe concussion that she suffered on holiday and the deaths of loved ones. After she recovered, she continued to cover conflicts until she was sixty-nine.

Brown is among the unbeaten ones. In fact, Feinstein’s surveys show many of those who cover wars emerge relatively unscathed: “Most journalists who choose conflict as their area enjoy what they do, are very good at it, and keep the life-threatening hazards from undermining their psychological health.”

After such a perilous life, Hilary Brown is happily retired in her mid-seventies, with a hot new love interest who’s keen to match her daring while whitewater rafting or hang-gliding — always “as wild and remote and as dangerous as possible.” And that, she concludes, “is just like being a foreign correspondent, all over again.”

Brian Stewart is a veteran journalist and former senior correspondent for CBC News who has covered conflicts and crises around the world.