Cobalt is a crucial resource for the twenty-first century. Frequently found alongside silver in geological formations, it is one of the most sought-after minerals in the world, with all kinds of uses in our digital age, including an important role in the lithium-ion batteries that power smartphones and electric vehicles. Cobalt is also the name of a small town in the Temagami region of northern Ontario, where in the early twentieth century silver deposits drove an explosive growth in the Canadian mining industry. Toronto — a five-hour drive south — became the financial centre of Canada thanks to Cobalt’s riches. Today the community is merely one of many shrunken mining towns dotted across a scrubby landscape, far from the urban centres that hug the border with the United States.

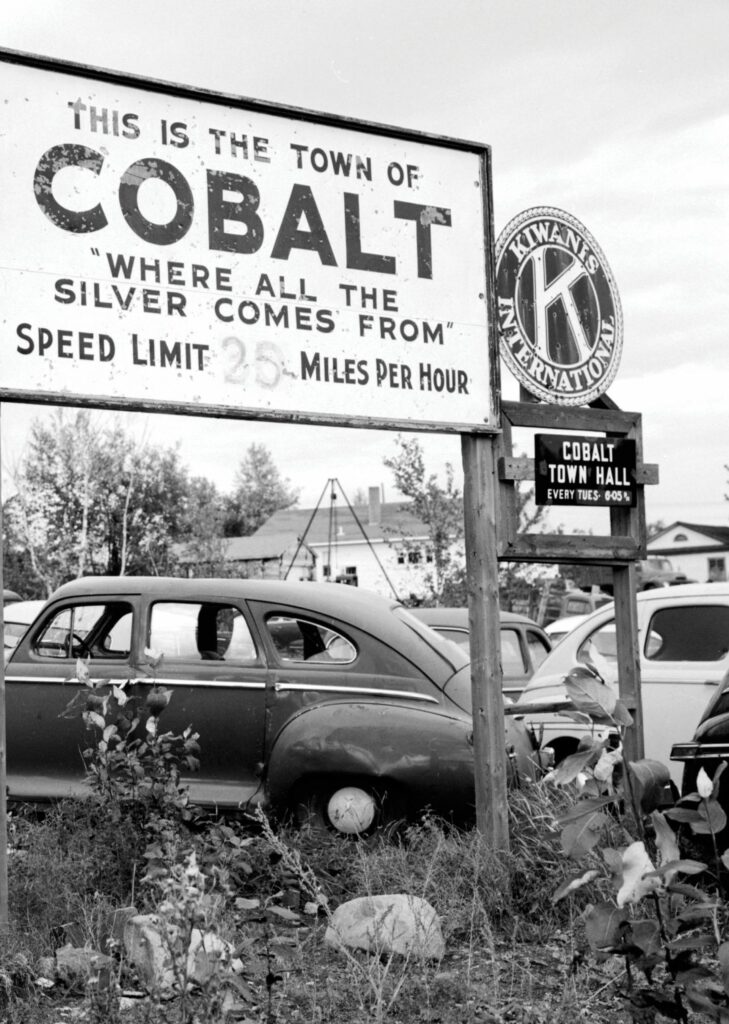

The contrast between the prosperity of those southern cities and the rundown state of Cobalt is not pretty. It is hard to believe that once this place hustled and bustled with the confidence captured in its town anthem: “We’ll sing a little song of Cobalt, / if you don’t live there it’s your fault. / Oh you, Cobalt, where the big gin rickies flow. / Where all the silver comes from / and you live a life and then some. / Oh you, Cobalt, you’re the best old town I know.”

I learned that bumptious song on a recent visit to Cobalt, but there was nothing lively about what I found there: boarded‑up shops, potholed roads, sagging roofs, and nowhere to buy a coffee. For that, I had to go to neighbouring Haileybury, where mine owners once lived in large stone mansions and flashy investors drank in hotels that had pretentious names like Vendome. Cobalt still has one promoter among its 1,100 residents, though: Charlie Angus, the New Democrat member of Parliament, lead singer of the alt-country band Grievous Angels, and forceful advocate for Indigenous rights, union strength, and the North.

The boom was soon over.

Berni Schoenfield, 1955; Stringer; getty

In Cobalt: Cradle of the Demon Metals, Birth of a Mining Superpower, Angus offers a history of his hometown, where he lives on an abandoned mine site, told from the point of view of those most directly affected by it: those who dwelt on this stretch of land. It is not the conventional settler narrative of white adventurers unlocking the continent’s hidden wealth that, until recently, was embraced in popular histories. It is an impassioned, often indignant exploration of how the North has always been treated as an internal resource colony, which was developed solely to enrich the southern metropolis. “Cobalt was a battleground for multiple visions of how the wealth of the earth could be used and who should be its beneficiaries,” Angus writes. “Issues of social justice that dominate the discourse today — resource exploitation versus environmental concerns and Indigenous rights; multicultural accommodation versus xenophobic suspicion; the power of the one percent in the face of class resistance — were battled out in the shabby streets of Cobalt.”

Angus’s first target is the brutal erasure of a long-standing Indigenous presence around Temagami. There had been a complex silver mining trade in the region for at least 2,000 years before white prospectors and railway workers discovered the precious metal close to Cobalt Lake in 1903. Once that happened, two local bands — the Saugeen Anishnabeg and the Teme-Augama Anishnabai — were rapidly dislodged from their traditional lands by the Ontario government, which was keen to open up the area for development. Next, Indigenous prospectors who legitimately made their own mining claims were elbowed off by white rivals. This was the era when the myth of the “Vanishing Indian” held sway, so their protests were ignored. Indigenous people watched the wanton destruction of the environment and their way of life.

The next cliché narrative with which Angus takes issue is the nationalist belief that the North was a proving ground for the young Canadian nation. The settlement narrative for the United States has always been about plucky homesteaders pushing the frontier westward. In contrast, the Canadian model of expansion has been one of entrepreneurs in canoes establishing northern outposts to exploit natural resources, despite pitiless weather and unforgiving terrain. In fact, those who benefited from the town’s resources were not locals; they were distant shareholders — primarily, in the early years, in New York, “the world’s foremost capitalist colossus.”

By 1906, there were sixteen mines in Cobalt that were producing loads of silver. In 1909, Maclean’s profiled thirty Canadians who had made millions in the region. “Wall Street is not the only throbbing, seething centre where fortunes of immense proportions are reared or dismantled,” declared the magazine, which went on to claim that the elite club’s wealth was due to “faith, courage and foresight” rather than happy chance. The newly established Toronto Standard Stock and Mining Exchange was soon a dominant player in the world of mining promotion. The Cobalt boom was the first in a series of staggeringly abundant booms in the North, which enriched the Toronto investment community, financed the city’s expansion, and laid the foundations for modern Bay Street. Today, three-quarters of the world’s mining companies are registered in Canada.

But alongside the productive mines, there were hundreds of companies selling stocks in Cobalt properties that had no credible mineral value whatsoever. Unscrupulous promoters manipulated gullible investors who craved the instant wealth they read about in newspapers. Angus argues that it was “a market driven by speculation, corporate gambling, and high-risk promotion,” and that, dazzled by the patriotic mythology of “the capitalist in a canoe,” regulators made little attempt to clean up market practices. And this helps explain why Canada now boasts a reputation as a “notorious haven for corporate money laundering.”

Meanwhile, back in the mines, life was brutal. Angus has done extensive research in unpublished memoirs and in newspaper archives, particularly of the local Daily Nugget, launched in 1907, to uncover the appalling conditions in which miners worked. No town planning meant that badly built shacks lined crooked streets, and polluted water caused regular outbreaks of typhoid fever. Without any form of worker protection, miners were underpaid and frequently injured. Medical services were severely limited. And there were no on‑site toilets; men regularly defecated in the tunnels. All settlers lived at the whim of the mining companies, which had the absolute right to tear down homes, sink shafts, or dump rock or garbage on anyone’s homestead. In Cobalt, mine owners ran the show, and they were ruthless and predatory.

At one point, the provincial Conservatives raised the idea of public ownership of natural resources. Why should American financiers grow rich on Ontario silver? Shouldn’t mineral resources be nationalized, as hydro resources had been? Mine owners ensured that the proposal went nowhere, and royalties were set at the absurdly low rate of 3 percent.

Angus enjoys taking apart another myth: that Canada’s mining camps were far more genteel than the rough settlements of the American West. An often-cited example is that of Elizabeth MacEwan, a prospector’s wife and Cobalt’s first woman settler, who described in a memoir how she was treated with chivalrous respect and enjoyed teaching Sunday school in a tent. Sex workers, though, had got there months before her. “Sex work as well as sexual violence and exploitation were clearly present,” Angus writes. Many of the workers were immigrants, and when they were abused, they went unheard.

The brutal conditions triggered resistance. In 1906, the Cobalt Miners’ Union was established and began pushing for increased wages, shorter hours, and safer conditions. The union boasted a diverse membership, including Black workers and immigrants from all over Europe. Yet in the town’s early years, when several of the local shopkeepers were Syrian or Jewish, there was remarkably little of the bigotry that was common in southern Canada. The following year, 3,000 men went on strike in the Cobalt area. In the short term, the action was broken in two turbulent months. In the long term, it helped force the passage of the Ontario Workmen’s Compensation Act.

The story that Angus tells is not entirely one of unmitigated misery. There is the tale of the Cobalt Silver Kings, a formidable hockey team sponsored by the silver barons, to which the Montreal Canadiens owe their origins. At one point, eight vaudeville theatres offered everything from full orchestras to risqué plays. But these were just sideshows. Angus provides convincing evidence that, in Cobalt more than in any other northern Ontario mining town, the provincial government, mining companies, and community leaders placed maximizing profits above providing for the most basic human needs.

Cobalt’s boom was over by the 1920s; the best silver ore was mined out, and nobody attached any value to the nearby cobalt deposits. Of course, the so‑called demon metal is in the news again. Angus notes that the billionaires Jeff Bezos, Michael Bloomberg, and Bill Gates formed a mining company in 2020 to seek out new sources of the mineral in northern Canada.

Cobalt is the best kind of popular history: carefully researched, vigorously narrated, respectful of the period it describes, but also informed by today’s concerns. Like good academic scholarship, it challenges long-held orthodoxies and makes readers rethink some of our cozy assumptions about this country’s past. Angus may be opinionated, but so was Pierre Berton, with his backslapping heroic narratives.

Angus’s account of the clash between predatory capitalism and the pursuit of social justice in one small Ontario town allows us to hear voices that have long been suppressed: those of displaced Anishnabeg and Anishnabai people, exploited immigrants, mistreated sex workers, courageous union leaders. His book is stuffed with the kinds of vivid details and large personalities that bring yesterday’s town alive for today’s readers. We can smell the squalor of the refuse piles and hear the groans of the typhoid victims.

But Cobalt does far more than this. It also reminds us that the Canadian economy was built on primary resources and that those industries are still key to the country’s prosperity. It asks whether today’s Canadians have learned the lessons about environmental damage, Indigenous rights, and corporate responsibility that one community’s residents learned a century ago.

This kind of narrative history is in decline in Canada today. Many university professors disparage it; major publishers show little interest in it; juries for non-fiction awards, like those run by the Canada Council, prefer personal memoirs to arm’s-length accounts drawn from careful research. The days when a Berton could notch up six-figure sales for well-written popular history are long over. An author needs dedication — and usually a day job — to persevere with a story that requires research, analysis, legwork, and craft.

I hope that Charlie Angus’s day job will continue to support him in producing spirited, well-informed, and provocative histories like this — and that his band might soon revive Cobalt’s town anthem.

Charlotte Gray is the author of numerous books, including Flint & Feather: The Life and Times of E. Pauline Johnson, Tekahionwake.