I may be wrong, but I don’t think most readers will happily pick up a book with a subtitle that promises an account of schizophrenia. Those who have experience with the serious mental disorder might be interested, but, then again, they might not. Those who knew Fraser Sutherland as a poet or an essayist might want to take a look, but they might not either.

I had better offer a rather painful personal story up front and acknowledge two conflicts that nevertheless don’t, in my mind, disqualify me from commenting on Sutherland’s The Book of Malcolm: My Son’s Life with Schizophrenia. The story has to do with my beloved mother, who was carried out of our Toronto house in 1960 screaming and in a straitjacket. I was fifteen. She spent over a year and a half in the Homewood Sanitarium in Guelph, Ontario, where she was subjected to involuntary electric shock treatments that, dreadful as they were, allowed her to escape the worst of the religious delusions that had overwhelmed her mind and body. At the time, I believed she was a victim of schizophrenia, but I now know it was an extreme form of bipolar disorder.

The two conflicts have to do with my sour attitude toward the author himself. First, there was the business of The Monthly Epic: A History of Canadian Magazines, 1789–1989. Let’s just say that in it, Sutherland was less than reverential toward Saturday Night, which I long thought was by far the greatest magazine in the history of this country. (Perhaps I held this opinion because I was its editor from 1987 to 1995.) Second, Sutherland’s lack of reverence for Saturday Night was compounded, in my mind, by his performance at Massey College in the University of Toronto during the period when I ran the place, from 1995 to 2014.

Sutherland had befriended a fellow poet who had arrived as a “writer-in-exile,” through a program for those dispossessed of their rights and livelihood in their own countries, thanks to dictatorial regimes or open hostilities or both. This particular poet — a classic lounge lizard, it seemed to me back then — had come from a war-tossed eastern European country, and we had arranged for him a small stipend for room and board, as well as access to our food and beverage facilities. Both the writer-in-exile and his new-found friend Sutherland quickly discovered that those facilities included a little bar in the college’s Common Room, where the two became semi-permanent fixtures.

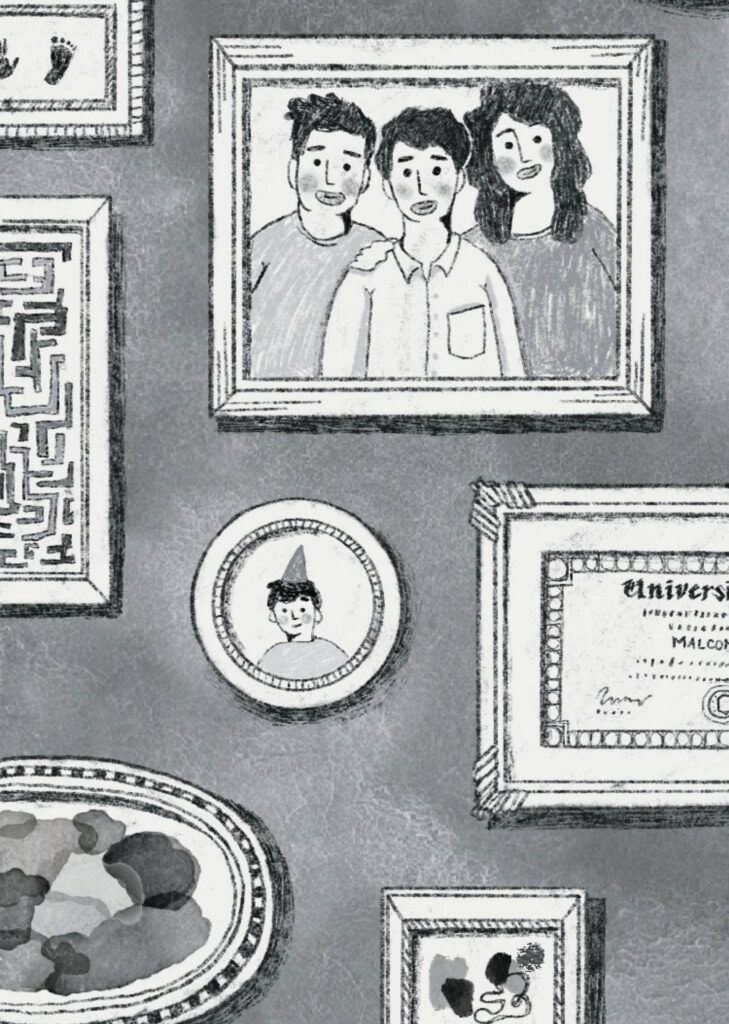

Family memories and personal reflections.

Nicole Iu

Every time I walked into the Common Room and saw the pair of them ensconced with their scotches — the college’s scotch! — it rankled. I tried being nice a few times, but I only ever got surly grunts from Sutherland and sheepish grins from the poet. Then, when the stipend ran out, the writer vanished into the local woodwork, and we never again had the presence of Fraser Sutherland inflicted on us.

So how do I now properly explain that a book about a father’s pain, over his deeply loved son’s desperate plight, brought me to tears? That it reminded me of the overwhelming desolation that mental illness in a dear friend or relative can cause? That it made me regret my unworthy and judgmental dismissal of his talent as a writer, and most of all made me wish I had been able to bring him some sort of solace and respite?

Malcolm Sutherland, the ostensible subject of this short but hugely compelling book, lived and breathed mostly in Toronto. The child of Fraser Sutherland and Alison Armour, he had Fraser forebears from Pictou County in Nova Scotia — as do I. He also had a metaphysical bent and wrote with enough whimsy and inventiveness to arouse pride in his writerly father.

It didn’t take me long to figure out why Fraser Sutherland wanted to compose this book, which he did while suffering serious health issues himself and while his wife was also dying. He wrote it first of all, it seems to me, to give Malcolm a chance to explain himself to the world and secondly — and most profoundly — to give Fraser Sutherland, grumpy to the end, a chance to explain himself to himself. We readers are decidedly secondary beneficiaries, but bona fide beneficiaries all the same.

In the first half of the book, Fraser gives Malcolm’s own voice free rein and keeps the Sturm und Drang of schizophrenia in diminuendo. The primary source material includes lovingly preserved diaries and letters, along with family accounts. Fraser also draws upon Malcolm’s personal reflections, about a “storm-toss’d” boy who enjoyed literature, philosophy, and religion (of all sorts); who soaked up both pop and esoteric culture like a sponge; and who had a “penchant for subversive mischief.” And though he died young, Malcolm’s writings are voluminous, and Fraser quotes from them judiciously. (When it came to my late mother’s writing, I learned to tune out her wildest imaginings so I could locate her heart’s core and know she hadn’t utterly abandoned or otherwise forgotten me. Malcolm’s father, I suspect, has done the same thing.)

The second half of the book brings the horror home, and I would not want to disguise what difficult reading it makes or the brutal honesty of both the father and the author — not necessarily, or at least not always, the same person. But the groundwork for the nightmare that comes is wonderfully prepared in that measured and warmly embracing first half, and you can take in some of the domestic horror scenes in the full knowledge that Fraser Sutherland, acerbic and often self-absorbed, was also a loving and protective dad who stayed the whole course to try to save his boy.

If the denouement isn’t a happy one, neither is it desolate. Malcolm was living at home when he died at the age of twenty-six on Boxing Day in 2009, after a seizure from an unknown cause. But that’s not how his father leaves him. Instead, it is with a one-sentence envoi: “Malcolm lay on the couch on the night of a much better than average Christmas Day, his eyes fixed on It’s a Wonderful Life.” Fraser, for his part, died before his final book saw publication.

The Book of Malcolm left me deeply and humbly regretting that I hadn’t had the wit to see beyond its author’s grumpiness all those years ago. That I hadn’t sat down with him and the writer-not-so-much-in-exile-anymore in the Common Room at Massey College. Even if I don’t much like the taste of scotch, I could have imbibed the insight of someone I now wish I had known a lot better.

John Fraser is the executive chair of the National NewsMedia Council of Canada.

Related Letters and Responses

@ekmushtghubaar via Twitter