What we tend to think of as the Rwandan narrative has been informed by the events of the 1994 genocide, of course, as well as by subsequent popular media and literary treatments, especially Roméo Dallaire’s anguished memoir Shake Hands with the Devil: The Failure of Humanity in Rwanda, from 2003. Much of what we understand to have happened between the Hutu-led Rwandan Armed Forces and the Tutsi-led Rwandan Patriotic Army has been the product of necessary “processing”— about an unthinkable crime against humanity, the horrific job of documenting the casualties, and the long task of ascribing legal responsibility.

Since 2003, the genocide has been commemorated each April 7 with an international day of reflection. The accepted explanation of what, exactly, is being commemorated continues to shift, though, especially following several surprising developments last year. And this year the grim task of contemplating the ultimate crime against humanity has taken on new meaning, considering the Ethiopian prime minister Abiy Ahmed’s brutal assault on the Tigray region and the Russian president Vladimir Putin’s invasion of Ukraine, which that country’s president, Volodymyr Zelensky, and other world leaders are already describing as a genocide.

The accepted narrative is changing.

M.G.C.

The Rwandan genocide ended in July 1994, three months after it started. Throughout, the non-governmental organization African Rights documented the slaughter, person by person, often in real time. The group issued its numbing report, Rwanda: Death, Despair and Defiance, in September 1994, with a revised edition the following year. Drawing upon that research, the BBC correspondent Fergal Keane published Season of Blood in 1995, which was followed by Philip Gourevitch’s classic account, We Wish to Inform You That Tomorrow We Will Be Killed with Our Families, in 1998. Two years later, Linda Melvern’s A People Betrayed set out damning evidence of the West’s role in the events leading up to April 1994, as well as that of the World Bank, the United Nations Security Council, and even the former UN secretary-general Boutros Boutros-Ghali. And in 2000, the Canadian journalist Gil Courtemanche published Un dimanche à la piscine à Kigali (translated by Patricia Claxton as A Sunday at the Pool in Kigali). A novel that was subsequently made into a film, Un dimanche à la piscine à Kigali depicts the romance between a white expat and a Hutu woman who is often mistaken for a Tutsi. In powerful ways, it brought to the public eye the very real phenomenon of rape as a weapon of war.

These accounts helped cement the now familiar narrative: Tutsis had been buffeted by colonialism, discrimination, and ancient hatreds. They had experienced tremendous suffering, culminating in a cataclysmic yet foreseeable catastrophe. All of these afflictions had rushed alongside a post-colonial stream of competitive struggles for influence between former European powers in their new Scramble for Africa.

Early on, the United States refused to recognize the events of 1994 as a genocide, even though Bill Clinton had reportedly read Gourevitch’s book and professed shock. In “A Problem from Hell”: America and the Age of Genocide, which won a Pulitzer Prize in 2003, Samantha Power explains that Washington was determined to avoid another African conflict following its withdrawal from the UN intervention in Somalia. The UN itself had to respond to critiques about its role in Rwanda, which was scathingly criticized by Dallaire. Its report, The United Nations and Rwanda, 1993–1996, did little to reassure the global community about the body’s effectiveness, let alone its commitment to human rights.

Over the past three decades, a second and very different narrative has also been in play — a competing version of events that has been especially evident in France, Belgium, and, sadly, Quebec. It posits the Hutu as the victims, the Tutsi as the aggressors, and the events of 1994 as an unfortunate by-product of a brutal conflict. The genocide did not happen, but if it did, it was overblown in the English-speaking press. One articulate advocate of this alternative storyline is the Quebec journalist Robin Philpot, who wrote Ça ne s’est pas passé comme ça à Kigali, a riff on and a direct indictment of Courtemanche’s novel. Published in 2003, the book rejected much of the received understanding of the genocide itself. Philpot denounced what he viewed as a form of sexual colonialism and disputed the versions of events put forward by Gourevitch, Melvern, and others. He also accused Dallaire of dissimulating before the international criminal tribunal in Arusha, Tanzania, where many of the masterminds of the genocide were tried.

Philpot is by no means alone in promoting this contrary narrative. Ideas like his were even on display at the Supreme Court of Canada in 2004, during a hearing about the deportation of the hardline Hutu activist Léon Mugesera, because of a speech he gave in 1992 that allegedly incited hatred, murder, and genocide. (He was ultimately deported in 2012 and convicted by a Rwandan court.)

The second narrative is different from the first in other key ways. In it, the avenging Tutsi forces downed the airplane that killed the presidents of both Rwanda and Burundi, widely seen as the event that sparked the genocide. And it paints the U.S. as the great villain, with loyal and morally just France simply trying to shore up Juvénal Habyarimana’s beleaguered presidency against the invading Rwandan Patriotic Front. Indeed, France has argued that it was trying to preserve its sphere of influence in a region where English was rapidly gaining a strong foothold.

The parallel streams of these competing accounts began to converge last year, with several developments that have challenged both the essentialist first narrative and the wildly counterfactual second one.

The first development was the publication of Michela Wrong’s Do Not Disturb: The Story of a Political Murder and an African Regime Gone Bad. The book focuses on the highly publicized assassination of Patrick Karegeya, the former military head of intelligence and Rwandan Patriotic Front member, in 2013. At the time of his death, Karegeya was living in exile in South Africa, but that offered little protection. Wrong details many instances of violence, intimidation, and surveillance by the regime and its paranoid, vindictive, and heavy-handed ruler, Paul Kagame.

Whispers of disquiet about the Rwandan government, and about Kagame, flitted around the world for years, but they had little lasting impact on the massive development aid flowing to a land where, Rwandans like to say, God comes to rest every night. But evidence of human rights violations and of brutal attacks on the regime’s critics are now beginning to challenge the dominant storyline, in which Kagame and the RPF are seen as shining saviours who ended the genocide and who deserve the West’s deference. While Wrong’s book does not break entirely new ground on this front, it is nonetheless important because it brings so much of the evidence together for the first time in an accessible and well-documented account.

Another development came last May, with the release of a shocking statement by Paul Rusesabagina, the hotel manager who had saved more than 1,200 people at Hôtel des Mille Collines in 1994 (the very hotel of Courtemanche’s novel, which has served as the favoured watering hole of le tout Kigali for as long as anyone can remember). Rusesabagina, whose story was brought to the screen by Don Cheadle in the film Hotel Rwanda, was visiting Dubai in 2020 from his home in the U.S. when he was tricked into boarding a flight that was supposedly bound for Burundi. But the Rwandan government, which has accused him of backing illegal militias, had secretly chartered the plane, and it took him to Kigali. Upon landing, Rusesabagina realized what had happened — and what was about to happen — and screamed for help. He was promptly arrested and charged with terrorism, and he was ultimately convicted in September 2021.

The statement disclosed that Rusesabagina had been subjected to four days of torture in an unknown location, and his lawyers say he suffered more than 260 days of solitary confinement, all serious violations of international law and Rwanda’s own constitution. His legal team has filed urgent appeals with the UN special rapporteur on torture. Meanwhile, Kagame publicly boasted about how the “perfect plan” had unfolded. At this point, none of these occurrences should come as a surprise to anyone — except, perhaps, the part about Rusesabagina still being alive.

A third thing happened last year, also in May: the French president Emmanuel Macron sought forgiveness for his country’s role in supporting Juvénal Habyarimana’s regime and its hard-core Hutu Power allies. The acknowledgement came on the heels of a damning thousand-page report issued on March 26. After reviewing more than 8,000 documents over two years, the Commission de recherche sur les archives françaises relatives au Rwanda et au genocide des Tutsis concluded that there was no evidence that France had been actively complicit in the genocide. But, the commission maintained, it bore responsibility —“heavy and overwhelming responsibility”— for investing in a regime that openly encouraged racially based massacres, remained stubbornly blind to the preparation of the genocide, and perpetuated a divisive and deadly Hutu-good/Tutsi-bad binary. The report also roundly criticized France for its belated and misguided Operation Turquoise, in the summer of 1994, which may have saved some lives but certainly not those of the Tutsi victims. (Dallaire also took aim at Operation Turquoise and the French government in Shake Hands with the Devil.)

Macron’s statement pulverized the French protests of innocence and flattened any claim to a moral high ground. It was long overdue — and warmly welcomed by the Kagame government. The two countries have since been rebuilding diplomatic and trade relations.

But none of that changes the growing disquiet about Kagame, his seemingly endless rule, and the human rights violations described by Wrong and many others. The United States, the United Kingdom, and various European Union countries, as well as international and intergovernmental institutions, continue to funnel development aid to Rwanda and its economic miracle. Wrong cites several sources who challenge the evidentiary foundations of that miracle, pointing out that the sparkling appearance of economic progress makes it easier for development partners to ignore evidence of violent repression.

Multiple reports and witnesses have provided evidence of extrajudicial killings, political executions, the jailing and exile of political opponents, threats and harassment of critics (including the media), and the marginalization of former allies who perhaps attract too much attention or international praise. Rwanda thumbs its nose at the global rule of law, thanks to the West’s hand-wringing over 1994 — its inaction and its moral if not operational complicity — and the fact that many Western governments have simply looked the other way ever since. While it is not one of the priority countries for Canada’s international cooperation in sub-Saharan Africa, for example, Rwanda nonetheless received almost $35 million from Ottawa in 2019–20.

Last year’s developments remind us that the imperative of reflecting on the genocide against the Tutsi, who made up 70 percent of the victims, does not preclude us from recalling the politicide of moderate Hutus and the mass murders of an oft-ignored minority group, the Twa. We can adopt a broader frame of reference without falling into the trap of genocide denial and without minimizing the moral and legal responsibility of those who perpetrated the genocide — and, indeed, without absolving the current regime of its own crimes. Established African authors and intellectuals have made such arguments by taking more contextual approaches. For example, Mahmood Mamdani’s When Victims Become Killers, from 2001, maps many of the historical, geographical, and political forces that led to the genocide.

The activist, journalist, and priest André Sibomana also did such work before he died in 1998. Sibomana was a francophone Hutu who had worked tirelessly to denounce the Habyarimana regime and to protect victims during the genocide. In many respects, Sibomana personified the strongly principled fusion of the two narratives that Wrong has resurrected with considerable success. As he was Hutu himself, Sibomana’s views had particular resonance and power. But he also spoke out courageously against repression, citing evidence of reprisal killings against Hutus and criticizing the excesses of the regime in his book, Hope for Rwanda. Kagame’s government took quiet vengeance when it barred Sibomana from leaving the country for medical treatment after he was struck with a rare and lethal illness.

During my second mission to Rwanda, in the early 2000s, I met a woman I’ll call Lily, who had been elected to the country’s parliament. Rwanda is lauded internationally for pro-woman governance policies and gender quotas (women now make up 61 percent of the Chamber of Deputies), but at least when I was there, it was still a deeply sexist and patriarchal society. Lily would speak out in the legislature, though, interrupting the men even when she had been told to shush. And, from time to time, she would be expelled for doing so.

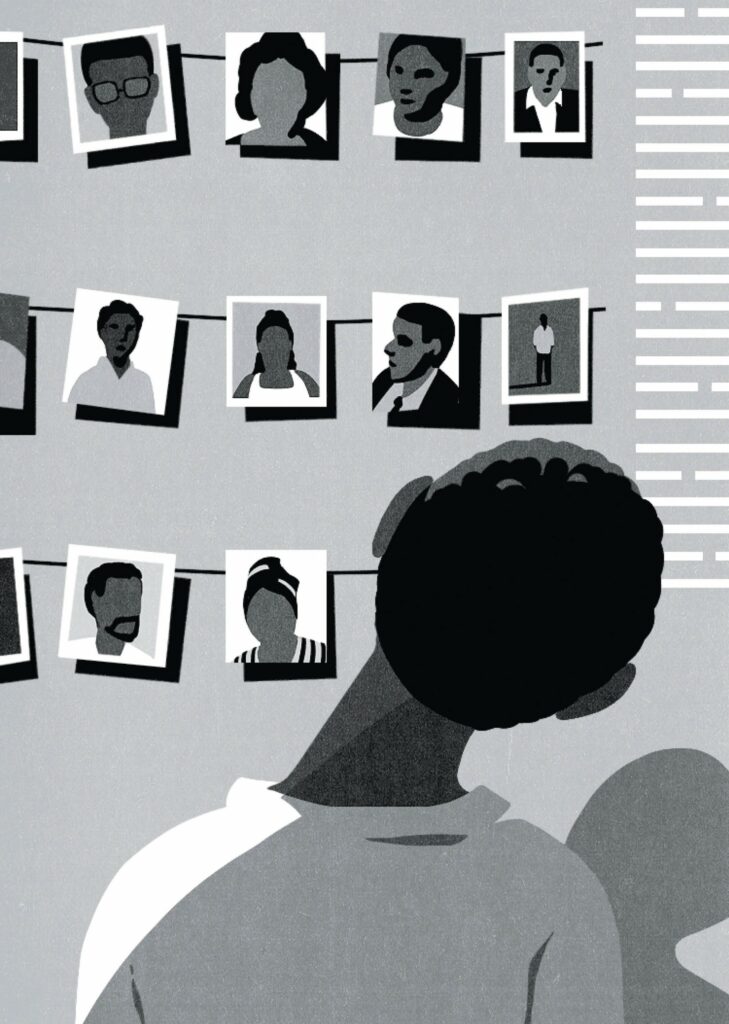

During one of her brief expulsions, Lily and I talked about the genocide and about reconciliation. The scale of the slaughter — some estimate as many as a million lives were lost over 100 days, in gruesome deaths meted out by neighbours and even family members, friends, and priests — remains incomprehensible. So was the attempt to pursue reconciliation as a matter of national policy, especially when so many had lost so much. At one point, Lily said the génocidaires had killed more than fifty members of her family.

“Fifteen?” I asked. “That is so many.”

She stared at me for a moment, with that particular look reserved for a clueless muzungu like me. I had clearly misheard. “No,” she said quietly. “I said fifty. More than fifty, actually.”

I wondered about the perpetrators — and how to deal with those who denied the genocide or who were actively trying to resurrect Hutu Power. “How can the Rwandese embrace all these reconciliation policies?” I asked. “What about justice?”

That look again.

“It is simple,” Lily eventually replied. “We have seen the alternative to reconciliation. No one wants that.”

For several years, I struggled to support international efforts to rebuild in Rwanda — and sometimes I still struggle to justify that work. Lily’s simple statement is the one thing that has been able to help me understand the country’s unity and reconciliation efforts, as well as the progress, albeit contested, it has made over three decades. Rwanda is in a volatile part of the world, with many internal and external enemies. The threat of violence is always nearby. I had and still have deep sympathy for some of the difficult choices facing Kagame’s government. But none of that means that Canada, or the world, should sit quietly by when fundamental human rights are flouted, opposition is silenced, and people are killed and threatened. Kagame is betting international applause for development and stability will outweigh the threat his authoritarianism poses to democracy. How the international community responds will have grave consequences for Rwanda and the stability of the entire Great Lakes region of Africa.

Pearl Eliadis went on three UN missions to Rwanda in the aftermath of the 1994 genocide. She practises law in Montreal.