Snaring Daniel Sanger’s attention requires comfortable boots, as his preferred hangout is ambulatory: the streets of Plateau-Mont-Royal, a densely populated stretch of century-old row houses three kilometres north of downtown Montreal. A storied immigrant quarter, now largely gentrified, the Plateau’s mix of music, gaming, and tech has made it one of North America’s hippest neighbourhoods. Saving the City offers both an insider account of how the area is gaining international recognition as a leader in urban redesign and a compelling primer on the inner workings of Montreal politics.

Sanger treads his turf with pride and purpose, as I learned on a recent walk with him (12,842 steps). This excursion netted an introduction to one of the borough’s new councillors (Marie Sterlin), a sighting of the federal environment minister (Steven Guilbeault), and a lengthy account of the controversial reconstruction of Théâtre de Verdure, in Parc La Fontaine.

Sanger, who grew up in Ottawa, was a founder of the alt weekly Montreal Mirror in the mid-1980s. He also worked as a Canadian Press reporter at Quebec’s National Assembly and an editor at Saturday Night, as well as an award-winning freelancer with The Economist, L’Actualité, Maclean’s, and the Guardian, among others. His first book was a best-selling portrait of Dany Kane, the Hells Angels informer.

In the mid-2000s, Sanger left the media to toil in the stony fields of activism, by joining a fledgling political organization that promoted tramways and bike paths over cars and advocated for wider sidewalks and greenery. Saving the City details how this grassroots movement turned into Projet Montréal, a broad-based political party.

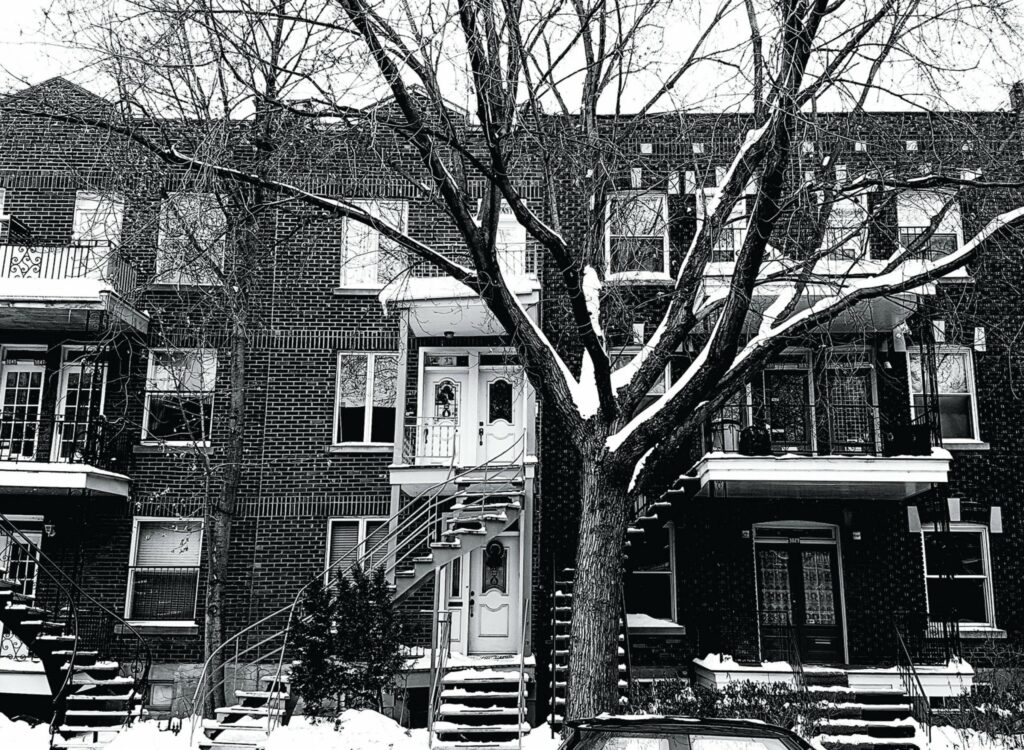

In one of North America’s hippest neighbourhoods.

Jason Thibault; Flickr

Projet Montréal’s first real victory came in 2009 with the election of Luc Ferrandez as mayor of the Plateau (municipal Montreal is a mini-federation, with mayors galore). Sanger then signed on as Ferrandez’s political attaché, which meant figuring out how to turn promises into accomplishments. The work required deep penetration into the foggy reaches of bureaucracies, making allies, and reading fine print — all familiar tasks for a former journalist. One of his early political missions was helping recruit new candidates from beyond the party’s largely white male leadership, an essential step if it was to outlast upset victories and effect long-term change. Among the new faces was Valérie Plante, who previously worked in communications for a suburban social services union. She was elected as a councillor in the borough of Ville-Marie in 2013.

What she lacked in experience, Plante made up for with moxie, ambition, and hard work. By 2017, she had become Projet’s candidate for mayor of Montreal, and, to the surprise of many, she beat the incumbent, Denis Coderre. A proud man with deep establishment roots and a fondness for car racing and stadiums, Coderre spent the next couple of years working out, losing a hundred pounds, and publishing a ghost-written book about his transformation from a Jean Drapeau wannabe to a man of the people. All for naught: in their 2021 rematch, Plante sailed to triumphant re-election.

Another recruit was Sanger’s long-time friend and colleague Sue Montgomery, a journalist who had written for the Montreal Gazette. In 2017, she was elected mayor of Côte-des-Neiges–Notre-Dame-de-Grâce, a largely anglophone and allophone borough and by far the city’s most populous. Imagining what he could do with more money and many more streets, Sanger moved over the Mountain to become her chief of staff.

But while Plante continued her learning trajectory — polishing her rough edges and tightening the reins on her personality-driven team — Montgomery discovered she hated the day-to-day slog of governing. In fact, she’d had a hunch that would be the case, and she had voiced reservations when courted as a candidate. She soon fell into a toxic war with city staffers and began to blame Sanger, who assembled the brick-like background tomes she could not bring herself to read. On a Friday afternoon in July 2019, after some internal restructuring, he was fired; a month earlier, a twenty-seven-year-old woman, whose self-described role was “to ensure that Sue is happy,” had taken over as chief of staff. The working atmosphere only got worse. When Plante insisted the aide be removed for psychological harassment of bureaucrats, Montgomery dug in, which prompted Plante to oust her from the party. (In last year’s campaign, Montgomery ran for re-election under her own banner and lost; her legal battles continue, with two Superior Court judgments in her favour.)

Sanger would have written a book about Projet Montréal even if he hadn’t been turfed. From the beginning, he had his eyes wide open, clocking anecdotes, judgments, and juicy details that would later be useful. Getting fired gave him time and motivation to put pen to paper, while the 2021 election added the golden gift of a deadline. Saving the City is much more than a personal memoir; in fact, “I” is the author’s least favourite pronoun.

Sanger conducted some sixty interviews, staying with the main players long enough that they relaxed and said what they really thought. In one of them, his old friend and former boss Luc Ferrandez explained, for the first time, his decision to quit politics shortly after Plante’s 2013 win: “I saw it becoming Équipe Valérie Plante,” he said of the party, a charge made by other insiders, including a number who also quit. As one unnamed borough mayor put it, “The biggest mistake Valérie makes is that she speaks in ‘Je.’ ‘Je fais ci. Je, je, je, je.’ And that excludes everybody else and it gives her less power because people don’t identify with ‘Je.’ And not ‘mon administration.’ I hate that. It should always be ‘nous.’ ” (Apparently Sanger isn’t the only one who dislikes the first-person singular.)

After the first few chapters, where dozens of names scramble for prominence, Saving the City is marked by great momentum and more than a few good laughs. Plante comes across as a live wire who interpreted the invitation to join the club as an invitation to run it. Like many women new to power, she sometimes had a hard time with other women. Sanger describes a live-streamed executive committee meeting during which Plante had an aide send Christine Gosselin, an elected member, several text messages telling her to “sit up straight and pull up her blouse.” Having spent years with Projet Montréal, Gosselin also eventually left the party — and politics.

Published in English and French, just weeks before the November vote, Saving the City was an instant hit among headline writers, whose mini-judgments often formed the substance of public discourse about the book’s content. An exception was the former Maclean’s columnist Paul Wells. After reading the French version, which came out first, he declared Saving the City “one of the most fascinating Canadian political books in an age,” one that combines “the clear eye of a very good reporter with the insider access of a sympathetic partisan.” Wells, who lives in Ottawa, even confessed he was jealous of people in a city where politics has substance and purpose.

The Montreal Gazette interviewed Sanger early on, but it decided to hold the story until after the election, possibly fearing a perceived conflict of interest. (Annalisa Harris, the woman who got his former job in Montgomery’s office, is the daughter of the Gazette’s chief editorial writer.) A few days before the vote, the paper changed course. “Fired former member of Projet Montréal releases tell-all book,” the tabloid-style headline read. “Author critical of party’s evolution and its leadership; recounts infighting.”

I asked Sanger to go on that walk not to talk about Saving the City but because I wanted his take on some broader questions: Is objectivity dead? Are all books ultimately a form of memoir? Is it possible to be an insider or activist and still uphold the values of journalism? Eventually, the conversation turned to the 2021 campaign. “She did a good job in her first term,” Sanger said of Plante. “She did what she needed to do to get elected, and she remains true to core Projet values. That merits a second chance.” He also confessed that his book and the subsequent media coverage had made him a pariah within the party ranks.

Sanger may have lost some long-time friends because of it, but Saving the City should be taught in politics and gender studies courses across the continent, as a case study of how women succeed and don’t succeed in power. By any measure, it is an important look at Montreal and an engaging account of how a small group of visionaries brought about real change in the early twenty-first century.

Marianne Ackerman has written many books and plays, including Triplex Nervosa, a trilogy.