Populism has fuelled Fascist and Communist governments and every brand of authoritarian regime in between. And while populist leaders have always pitted the people against the elites, figuring out which is which has not always been easy. There has been no such confusion in Saskatchewan. Indeed, in the long, murky history of populist movements, there should be a special chapter set aside for the Land of the Living Skies.

Even before Saskatchewan became a province in 1905, the people who lived there were bathed in a profound sense of grievance that the federal government, the banks, the grain companies — indeed, almost everyone was against them. The extraordinary thing about the province, however, is that in the past fifty years it has remade itself from a society with collectivist inclinations into one that is centre-right in most of its policies. As Dale Eisler tells it in From Left to Right: Saskatchewan’s Political and Economic Transformation, this hasn’t necessarily been an ideological shift; rather, it has been a pragmatic response to larger issues in the world.

The many immigrants who flooded into Saskatchewan at the beginning of the twentieth century were conservative in that they cherished owning their own land and profiting from their own labour. But they asserted themselves within a collectivist framework that had not been seen in North America. In a bid to get away from the private grain companies and eastern banks they thought were cheating them, they founded their own co-ops and credit unions; a decade after the creation of the Co-operative Commonwealth Federation, they luxuriated in a government led by the estimable Tommy Douglas.

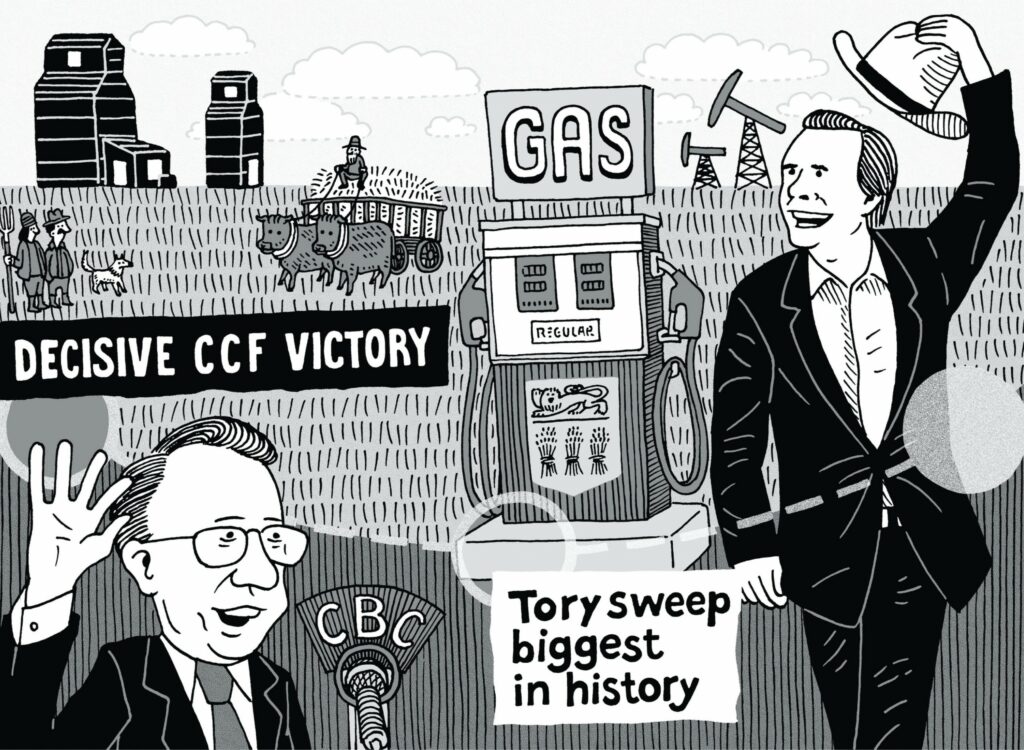

In the 1944 election, Douglas offered voters a choice between the conditions as they were before the Second World War — essentially private enterprise and poverty — and what the CCF called a commonwealth of social justice. The party went on to enjoy twenty years in power — seventeen of them with Douglas as premier — because it knew what the predominantly rural province needed. Douglas wasn’t a farmer (he grew up in Scotland and Winnipeg), but his brand of religious populism and his powerful oratory delivered five majorities.

The transformation of Canada’s breadbasket may not yet be complete.

Tom Chitty

Once in office, the CCF turned Saskatchewan on its head. Within eighteen months, it passed an incredible 196 pieces of legislation, many of them dealing with rural issues, such as electrification, crop insurance, and foreclosure protections. By 1947, the government had taken the first steps toward the universal health care that the rest of Canada later adopted.

The introduction of medicare in 1962, after a short-lived strike by doctors, was arguably the high-water mark of the CCF, which then merged at the provincial level with the New Democratic Party. Douglas was replaced as premier by Woodrow Lloyd, a bland former high school teacher. Two years later, the combined CCF-NDP was defeated by the Liberals and their mercurial leader, Ross Thatcher. The ousted party dropped the CCF part of its appellation and in 1971 regained office with a landslide victory, but the subsequent fifty years have not been particularly kind to it.

Since 1971, the provincial NDP has formed two long-lasting governments — from 1971 to 1982 and from 1991 to 2007 — though its share of the vote has steadily declined. Yes, support for political parties ebbs and flows, but Eisler argues that something else is afoot: “The Saskatchewan of today is far different from the province that was once seen as something of an outlier in terms of taking a different political and economic approach than others.”

The tale of the NDP’s marginalization in the birthplace of the CCF is a lesson in the shape-shifting of populism. The province still has a chip on its shoulder about the chauvinism of Ottawa and Toronto, but few would assert today, as the Globe and Mail ’s Robert Sheppard did repeatedly in the 1980s, that Saskatchewan is the country’s most distinct society. It was an arguable proposition then, but it’s laughable now. It’s just a mountain-less Alberta, dependent on resource revenues and replete with right-wing attitudes.

So what happened? In his decisive analysis, Eisler settles on what he calls a “before and after moment” in 1982, when Grant Devine, a young Progressive Conservative who had never held elected office, found a way to exploit prairie populism from the right — and demolish the decade-old NDP government of Allan Blakeney. During that year’s campaign, Devine projected unlimited enthusiasm and, customarily wearing blue jeans and a cowboy hat, promoted himself as a guy who understood ordinary people. He described himself as “just a farmer who happened to get a PhD degree.” Of course, it didn’t hurt that he promised to remove the 20 percent provincial tax on gasoline. A day after the election, which reduced the NDP to a mere nine seats in the sixty-four-seat legislature, my father ruefully noted that Devine “bribed us with our own money.”

Blakeney was an easy target. A former Rhodes Scholar born and raised in Nova Scotia, he was more comfortable leading a discussion of public policy than chatting with farmers. His ambitious government created successful Crown corporations to provide essential services, and he defended his party as “tested and trusted.” But Devine portrayed Blakeney as a technocrat out of touch with voters who were facing high interest rates and low crop prices. “Rusted and busted,” Devine would say. His campaign slogan was also pure populism: “There’s so much more that we can be.” On election night, Devine told giddy Conservatives: “The good old province of Saskatchewan is not going to be the same anymore.” And, for once, the victor followed through on his bravado.

Devine was eventually undone by his practice of running Saskatchewan as if it had endless pots of money. Although his government incurred massive deficits in the 1980s, he was not chagrined. As premier, he “seemed unfazed by the financial incompetence of his government,” concluded Bill Waiser in his exhaustive Saskatchewan: A New History, from 2005.

Voters returned the New Democrats to office in 1991, but the party under Roy Romanow inherited a poisoned chalice: the largest per-capita debt in Canada. With low commodity prices and credit-rating agencies breathing down the province’s neck, Romanow moved quickly to restore fiscal balance. He did so largely by closing rural acute-care hospitals and by implementing a range of tax increases. There was no money for the type of public service initiatives previously championed by the NDP. However adept Romanow was at dealing with the debt he inherited, his actions left a widespread impression in the countryside that urban interests now dominated New Democratic thinking. The party won again in 1995, but voter turnout suggested a waning of enthusiasm. Things were worse four years later, when the NDP was reduced to a minority, winning fewer votes than the two-year-old Saskatchewan Party, which had arisen from the ashes of the scandal-tarnished Progressive Conservatives.

The Saskatchewan Party profited from rural anger. Indeed, all the seats it won in 1999 were in rural areas, while the NDP retreated to urban strongholds. Under a new leader, Lorne Calvert, the New Democrats hung on for a two-seat victory in 2003, thanks to strong resource revenues and an inept campaign by the Saskatchewan Party. The 2007 election, however, was a different story: under its own new leader, Brad Wall, the Saskatchewan Party won the first of three majorities — each one larger than the one before.

For all their differences, Eisler sees something of Douglas in Wall, with his “ability to reduce politics to emotion that transcends politics.” This skill was clearly on display on election night in 2007:

Wall took what was an intensely partisan event and turned it into an exploration of the spirit described as the essence of the Saskatchewan myth. In fewer than three minutes he delivered a political message that was less about politics and more about the unifying thread that binds people together regardless of their political beliefs. The fact that his message was distilled into a false binary choice that did not truly reflect the political divide did not matter.

That’s certainly one way to illustrate the brand of populism found in Saskatchewan.

Wall framed his message in terms of hope and fear — the hope for better crops next year and the fear of foreclosures from eastern banks. It was as potent in the 2000s as it was in the 1930s. And he cemented his standing with voters in 2010 by leading the fight against an Australian firm’s hostile takeover of the province’s leading potash mining firm. As premier, he flew the flag of economic nationalism and left the NDP little room to manoeuvre. A year later, he won his second majority, with a remarkable 64 percent of the vote. The NDP, which has had six leaders since 2009, remains in the wilderness.

A new Saskatchewan Party leader, Scott Moe, won another massive majority in 2020, but he doesn’t seem as deft or as popular as Wall. And, like the NDP a generation ago, he will be looking over his shoulder as a coalescing grievance fuels a push for a provincial independence referendum. The Buffalo Party was formed just four months before the 2020 vote, and it fielded a limited list of candidates. Nevertheless, it finished second in four ridings — ahead of the NDP. The transformation of the province may not yet be complete.

Those of us who grew up in Saskatchewan in the 1950s and 1960s may never have heard the term “populism” back then, but we knew what we were about. We weren’t Alberta, which had responded to the horrors of the Great Depression by embracing private enterprise and the right-wing lunacy of the Social Credit movement. And we believed in — or at least accepted — Crown corporations that made such disparate products as bricks and shoes, because we couldn’t trust the forces in Central Canada. The circumstances and the terminology may change, but, as Eisler shows in his important book, the attitudes don’t.

Murray Campbell is a contributing editor to the Literary Review of Canada.