As a genre, Experimental film has frequently — and justifiably — been excoriated for a sort of brutalism. Writing in The New Republic in 1966, for example, Pauline Kael commented on its pompousness, impersonal dexterity, clever gimmicks, and plain messiness, as in “uneven lighting, awkward editing, flat camera work, the undramatic succession of scenes, unexplained actions, and confusion about what, if anything, is going on.”

Kael was not hostile to the experimental work of skillful filmmakers, such as Bruce Baillie, Carroll Ballard, and Jordan Belson. Her scorching focus was on young Americans who, in reacting to “the banality and luxuriant wastefulness which are so often called the superior ‘craftsmanship’ of Hollywood,” went to the other extreme. “Craftsmanship and skill don’t, in themselves, have much appeal to youth,” she wrote. “Rough work looks in rebellion and sometimes it is: there’s anger and frustration and passion, too, in those scratches and stains and multiple super-impositions that make our eyes swim. The movie brutalists, it’s all too apparent, are hurting our eyes to save our souls.”

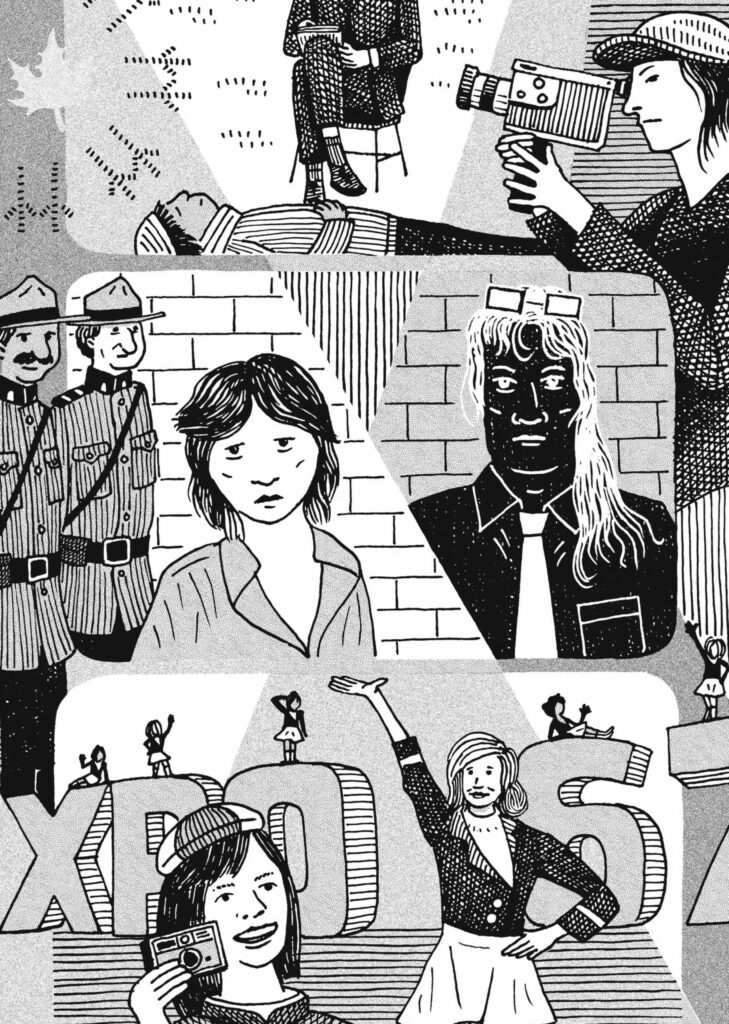

All art is experimental in a fundamental way, because every individual work creates its own reality through its own artifice, whether in painting, sculpture, poetry, drama, fiction, music, dance, or film. And because experimentation always seeks to expand boundaries, it is ludicrous to adopt a Procrustean perspective about art. One size does not fit all, as even a cursory consideration of the work of key filmmakers reveals: the silent-movie techniques of Guy Maddin; the optical printing and special camera mounts of Chris Gallagher and Alexandre Larose; the text-as-image signature of Kelly Egan and the hand-drawn scratches and squiggles of Norman McLaren; the near-abstraction of Carl Brown and Louise Bourque; and the fragmentary elasticism of Lumière’s Train (Arriving at the Station) by Al Razutis. But the moment we try to philosophize or to pin down definitions, we encounter trouble — as is clearly shown in Michael Zryd’s lengthy essay in Moments of Perception, one of two recent books that attempt to map experimental film and video in Canada.

Zryd’s “A Short Institutional History of Canadian Experimental Film” anchors a three-part volume that “is designed to provide an overview of artists’ film as an expression of Canadian culture — including all the contradictions and complexities of that term.” Unfortunately, Zryd, a cinema and media arts professor at York University, gets entangled in academic convolutions and contortions. Acknowledging the difficulty of definitions — because terms such as “Canadian, experimental, and film itself” have changed considerably over time — he spins his intellectual wheels in rhetorical dry dust. “Define Canadian,” he writes. “I dare you. . . . Define experimental. I double dare you. . . . Define film. I triple-dog dare you.”

Pushing the boundaries of film and video.

Tom Chitty

The only ones who are actually apt to worry about such definitions are scholars and their captive students. But Zryd persists and contaminates an otherwise useful essay by resorting to truisms or self-evident facts: “I would assert that the unique quality of experimental films is that each film invites a new approach by the viewer.” “That which is avant-garde one year has a tendency to become next year’s fashion.” “The ‘quality’ of a screening has many variables.” “Seeing film on film is complicated.”

Zryd surveys a great deal of territory as he takes into account Indigenous filmmakers, multiculturalism, regional aesthetics, and many mutable factors that affect the growth and scope of experimental film. He offers a chronological history, moving from west to east to north, covering the National Film Board, Norman McLaren, and various film societies. He also describes 1967 as a pivotal year, as expressed by Expo 67; Intermedia, a collective that brought together artists, scientists, and speculative thinkers; the Canadian Film Development Corporation (later Telefilm Canada), whose story is “baroque in its complexity”; and the Canadian Filmmakers Distribution Centre, which was “kick-started by Cinethon, a three-day international underground cinema marathon” that Robert Fothergill and Lorne Lipowitz organized. Zryd’s heavy and often dreary style is a demerit, though he occasionally lightens the tone, as when he quotes the Saturday Night columnist Robert Fulford on the contrast between Expo 67 and Cinethon: “The atomic bomb is one of two favourite symbols in the underground cinema. The other is the female nipple. At Expo the two main symbols in the films are the umbilical cord and the rocket ship. This defines the difference between the free and the subsidized cinema.”

The film historian and filmmaker Stephen Broomer contributes Moments of Perception’s second essay, which is more lively, specifically analytical, and beautifully enhanced by filmographies and colour plates. In profiling many leading experimentalists, Broomer’s thoroughly compact text leads readers into areas of multi-screen emulsion lifts and abstract collage (Christina Battle); plastic manipulation of the film plane (Louise Bourque); intertextuality (John Hofsess); psychodrama (Carl Brown); found footage (Arthur Lipsett); photography as memory object (Jack Chambers); minimalism and maximalism (Mike Hoolboom); colour saturation and spectral effects (Alexandre Larose); digital scans (Josephine Massarella); complex repetition and variation (Barbara Sternberg); abstraction of figure and environment (Daïchi Saïto); video compositing (Michael Snow); optical printing (David Rimmer); and connections between film and painting (Joyce Wieland).

The third essay, written by the volume’s editors, Jim Shedden and Barbara Sternberg, is little more than an anthology of snapshot analyses, with mini-bios and filmographies of dozens of other experimentalists. Admirable though this section is, the sad fact remains that most of the names and films are unknown to many if not most cinephiles.

Which returns us to the fundamental questions raised by Shedden and Sternberg in their brief introduction: “Why this book? And why now?” After noting “a resurgence of production in Super 8, 16mm, and 35mm by film artists — young film artists” and “a return to materiality and to artisanal, hands‑on filmmaking” that has garnered international attention, Shedden and Sternberg suggest a reasonable answer: insight into how film —“the background of our lives”— helps shape our culture’s stories and memory.

Edited by Jon Davies, More Voice-Over: Colin Campbell Writings focuses on one of North America’s most important video artists, whose works have been exhibited internationally and are in permanent collections of the Museum of Modern Art, the Art Gallery of Ontario, and the National Gallery of Canada. Davies, a former curator now pursuing a doctorate at Stanford, presents a huge selection of Campbell’s texts, including scripts, magazine articles, lectures, artist’s books, short fiction, and excerpts from his two unpublished novels.

Born in Reston, Manitoba, in 1942, Campbell died of cancer in Toronto in 2001, leaving behind what Davies calls “a marvellously idiosyncratic body of work.” A pioneer in queer video who spent several stressful decades fighting censors, critics, and social mores, Campbell was preoccupied with identity, which he considered “always mercurial, malleable according to one’s moment-to-moment whims, power dynamics, and the desires of others.” Campbell’s various personas evolved over the years, from the petulant Art Star of the early ’70s and the gossipy Woman from Malibu later that decade to the pansexual expatriate Colleena in the late ’90s. Davies describes him as “playfully fluid in his sexual and gender identifications and affiliations,” someone who distinguished himself as “master/mistress” of monologues.

Davies’s introduction is a substantial tribute that foregrounds Campbell’s role in the early history of video — an art form that the critic John Bentley Mays once intemperately and ridiculously denounced for being in “perpetual infancy,” because it is “the first artistic activity in history to refuse absolutely to ‘develop.’ ” Campbell rebutted such statements with a potent article in Only Paper Today, an art magazine, and with scripts that, like the video genre itself, tended toward fabulism, narrative (rather than pristine formalism), and speaking (rather than showing). Davies comments that Campbell’s writerly voice is that of “an outsider-observer, keenly probing beyond appearances in order to reveal all the queer subtext and repressed drives — and politics — beneath the surface.” This trait is particularly evident in Modern Love, Bad Girls, and Rendez‑vous as well as in the unpublished novels “The Lizard’s Bite” and “Disappearance.”

The filmmaker Mike Hoolboom described Campbell’s oeuvre this way:

His tapes are heady with celebrity mentions and drive‑by shootings after all, censorship lampoons and AIDS protests, all signs of the times, right? And if those weren’t evidence enough that the news ticker’s heartbeat ran straight up the mainline of his work, there were even a pair of movies made at Toronto insider hotspots which not only celebrated clubhouse passions, but became part of their legend.

All was not sweetness in Hoolboom’s considered reflection, however, as he pinpointed shortcomings in Campbell’s work: primitive editing with a razor blade sawing through ribbons of tape, “leaving an ugly scar in the middle of each frame”; sound “funneled live into a microphone nipple perched on the camera, ensuring maximum line hum and glorious mono”; a usually stationary camera filming close‑ups and yielding grey, white, and very soft images. I would add often underwritten or overwritten scripts that described rather than showed action. In other words, no‑frills productions that, in retrospect, could be considered bargain basement art.

All history needs to be put into context, however. And while Davies’s exhaustive book reproduces too much material that is inferior, it plays an important role — just as Moments of Perception does — in tracing a culturally relevant art form’s history from its raw, unsophisticated beginnings to contemporary, ever progressing achievements and exquisitely artful visions and insights.

Keith Garebian has published thirty books and five chapbooks, including the poetry collections Three-Way Renegade and, most recently, Stay.