Martha Schabas’s latest novel has a simple premise: After travelling to England for what turns out to be a disastrous audition, an actor in her late twenties meets a suave older man on a train, who offers her a place to stay in London in exchange for suspiciously mysterious “work.” Back home in Toronto, she decides to risk the life she knows for one she doesn’t. Leaving behind her husband (regretfully) and her mother (joyfully), she finds herself in a new city that quickly engulfs her in its seedy underworld. She may not be living well, but at least she feels alive.

In part, Schabas has recycled the set‑up from her first book. Published over a decade ago, Various Positions is another story about artists and the cost of artistry in which a young, neurotic woman falls for a sketchy yet intriguing older man. With My Face in the Light, she returns to a self-conscious first-person narrator in Justine, who lies to her devoted but helpless husband, Elias, telling him that she got the London gig. Despite years of relative contentment, Justine feels stifled by her marriage and wonders if the grass is, in fact, greener on the other side of the Atlantic. Schabas is at her best when parsing the ineffable, unspoken aspects of relationship turmoil, of unhappiness in the midst of happiness: “While I felt the usual pang of tenderness at the impression he cast — so tall and imposing, momentarily defamiliarized from our relationship — I also felt a wave of dread.” The tale of the couple as they meet, grow together, fight, and eventually part ways is compelling for its slice-of-life minutiae.

Justine loves her husband but must break free from him. Unlike the novel’s driving narrative — the story of the man on the train, which demands a certain leap of faith from a reader — nothing in its depiction of marital disillusionment is unearned or unrewarding. When we leave Elias in Toronto, we feel as he does: sadder and wiser, chastened by life’s inadequacies. The third layer of the story, which concerns the narrator’s estranged mother, Rachel, a successful painter, is equally textured. Justine feels the gravitational pull of the woman’s judgments and achievements whenever she tries to stretch her wings and soar. She remains addicted to Rachel’s approval as well as berated by her not so maternal voice. The book opens when Justine unexpectedly turns up at her mom’s house after they haven’t seen each other for two years. At the door, “she stared at me blankly for a moment, then made a face I knew all too well. You cannot surprise me, it said.”

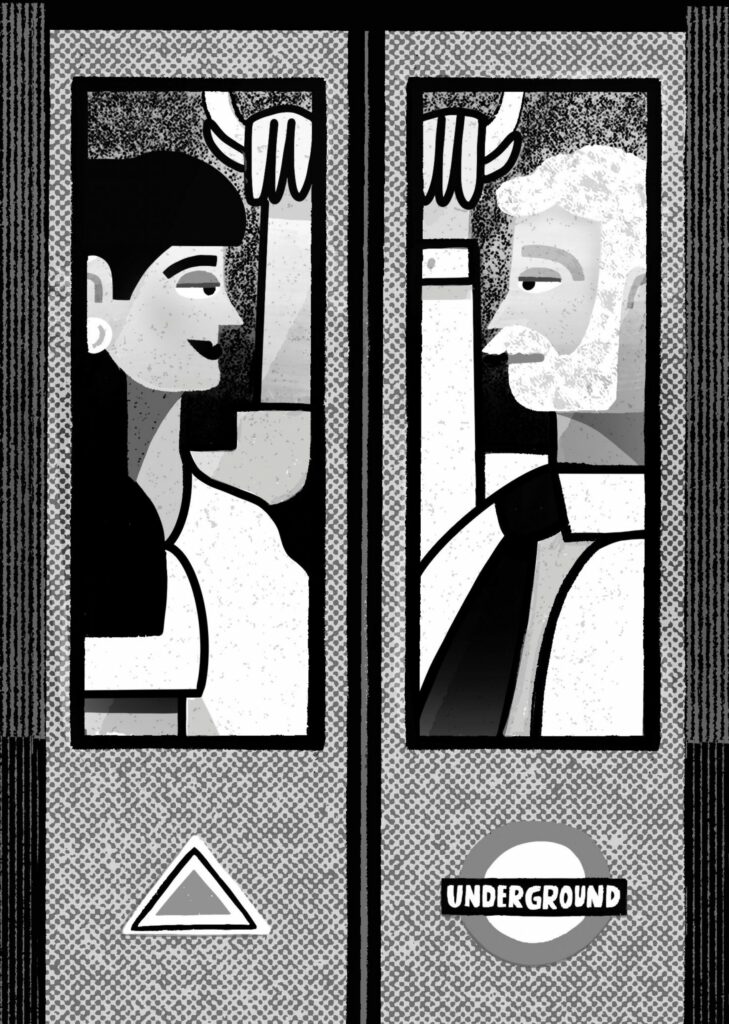

The suffocation of these emotional ties — one through closeness, the other through distance — prompts Justine to roll the existential dice on the mysterious stranger. A few months after their chance meeting, she accepts his offer and moves to London, where she ends up working in a gentlemen’s club (for rich lechers) above a strip club (for poor ones).

Theirs was a chance encounter.

Sandi Falconer

This narrative left turn, away from Schabas’s mundane yet engrossing case studies of intimacy — between husband and wife, mother and daughter — signals a shift in the novel’s thematic terrain. No longer are we concerned with the intricacies of the ordinary and domestic. Instead, readers are thrown, like the narrator, into uncharted, destabilizing territory.

Life in London is exciting, exotic, and dangerous, but this sudden upheaval comes across as though the author is obeying an editor’s note to “raise the stakes.” Previously the novel had been absorbed in the poetry and drama of the everyday, its quiet moments of desperation, which Schabas examines so skillfully. Justine was fascinating as she was, as she second-guessed herself and longed for an existence that was seemingly just out of reach. It is tempting to wonder what kind of book this would have been if Schabas had let her protagonist stay in Canada and deal with her problems head‑on.

Self-awareness is something My Face in the Light possesses in spades. A more thoughtful, reflective gaze would be hard to find. Schabas is sensitive to nuances, both internal and external, and articulates shades of meaning through vivid, precise prose. Squirrels have “spikes of silver fur” and couples have “desperate sex,” in which it isn’t clear whether they are expressing their “fear of losing each other or performing some physical interpretation of a breakup itself.”

The novel specializes in psychological set pieces, filled with suggestive dialogue, astute asides on how adults try (and fail) to act like adults, and penetrating, digressive commentaries on the human condition. At one point, when Justine is considering what qualities she admires in men, she confesses, “It was blatantly sexist, but the nobility of simple motives had always seemed like the mark of great manhood in my world, while I afforded women all the normal messy vicissitudes of human psychology and feeling.”

Schabas has a tendency to dramatize a scene, then analyze it, then analyze the analysis. “I always said the wrong thing,” Justine reflects upon meeting with her sister-in-law, “as though her expectations (or what I perceived them to be) conditioned my behaviour pre-emptively.” Anna is warm and uninhibited, everything that the narrator thinks she is not: “Sometimes I wondered whether I was sharp and cold and brittle only to lend weight to her assumptions.” One walks away from such passages with a heightened sense of reality, as if one has taken a drug that enhances perception. The downside of this relentless observation and examination, what the critic James Wood has termed “serious noticing,” is that the writing can become locked in loops of contemplation that offer little tonal variation.

As crisp as Schabas’s sentences are, as much as they are executed with poise and grace — and here, her former role as the Globe and Mail ’s dance critic is most apparent — the strain of maintaining such a stiff, demanding form is evident throughout. The steely prose rarely slips, rarely takes risks, relying instead on the protagonist’s decision to upend her life for tension.

What is missing from Schabas’s bag of storytelling tricks, as in Various Positions, is a sense of play, a hint of self-deprecation, as opposed to mere self-consciousness, to cut through the richness of the observation and the intensity of the drama. But these are minor complaints in an otherwise excellent novel, one that improves and expands on the emotional and conceptual topography mapped by its predecessor.

Chris Gilmore wrote the collection Nobodies.