Emily St. John Mandel’s novels often feature a moment of disorientation — a brief shift in point of view from the third to the first person, for instance, or a quick jump in time — that unsettles a stable reality and leaves the reader suddenly adrift. Her latest work, the layered and dazzling Sea of Tranquility, doesn’t take long to reach such a juncture. It opens, like her previous book, The Glass Hotel, on a ship. This time it’s 1912, and eighteen-year-old Edwin St. John St. Andrew is headed to Canada from England after being exiled from his family.

When Edwin eventually gets to the West Coast, he goes for a walk on Vancouver Island. In a patch of dense forest, he encounters “a flash of darkness, like sudden blindness or an eclipse,” and hears the notes of a violin. He wakes up on a beach with a vague memory of having fought his way out of the trees. In a nearby church, a priest who had appeared in the woods, seemingly out of nowhere, right before the incident, offers him counsel. But a few pages later, the priest has fled, outed as an imposter. The world has shifted, and we readers are adrift once again.

The rest of the novel circles this strange event, tracing its connections to other supernatural occurrences — one caught on film in the late twentieth century, another described in a book three hundred years in the future — that feature the same violin music. As the tale winds through the centuries, Mandel’s prose and plotting are as propulsive as ever. The nature of her detective story, with its shifting perspectives and returns to shared moments, reflects her penchant for weaving intricate, interconnected worlds.

Mandel’s structure goes beyond overlapping storylines. As in her previous novel, she picks up the narratives of familiar characters. In one timeline, we are reintroduced to Mirella Kessler, who attends a concert by the composer and video artist Paul James Smith to find out more about the fate of her friend Vincent (Paul’s sister). All three are transposed from The Glass Hotel, and here their lives intermingle with that of Gaspery Roberts, a man who seems dislocated, in some way, from the present. Gaspery has come to New York to inquire about a piece of Paul’s music that connects back to Edwin’s vision in the woods.

A world overflowing with meaning.

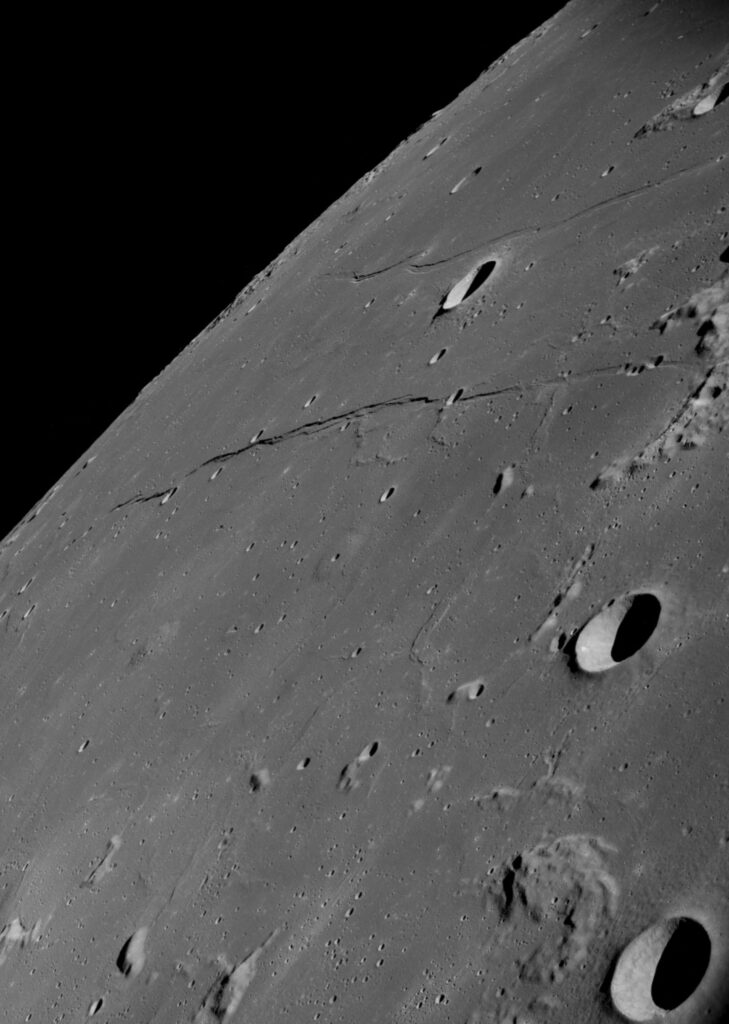

Apollo 8; Johnson Space Center; NASA

In a later section, we meet Olive Llewellyn, a writer in the year 2203, who, after “three books that no one noticed, no distribution beyond the moon colonies,” is on a tour to promote a new edition of her bestseller, Marienbad. Besides the inclusion of a scene where a character, on hearing a violin, briefly feels transported from the world around him, Marienbad is a tale about a pandemic —“a scientifically implausible flu,” as Olive tells a taxi driver. “Have you been following the news about this new thing,” the driver responds, ominously. “This new virus in Australia?”

Mandel, too, published three books before her 2014 pandemic title, Station Eleven — a work that felt eerily prescient once the COVID‑19 crisis hit. In Sea of Tranquility, she injects herself into the story and becomes a piece in her own puzzle. Like the unexpected appearance of individuals across multiple plot lines, the spark of recognition from the Olive-Mandel connection lifts the reader temporarily out of the narrative. It creates yet another unsettling moment, one that spotlights the author’s web as it spreads into the distant future, into other fiction, and, more explicitly than before, into real life.

The structural machinations in Sea of Tranquility, also play off an instability at the heart of the novel, one that emerges most clearly in its final storyline. Gaspery’s sister, Zoey, works at an institute that has mastered time travel. Her job is to investigate anomalies in the timeline that might be caused by errant travellers. In particular, Zoey is looking into the events linked to Edwin’s experience in the forest. “If moments from different centuries are bleeding into one another,” she tells her brother, one could “think of them as corrupted files.”

Zoey’s (and, eventually, Gaspery’s) inquiries suggest a destabilizing truth about the very foundations of existence. As the book proceeds, the fragility of the world becomes a central concern. In a lecture on the continued appeal of post-apocalyptic literature, Olive reflects on her mother’s life in the mid-2160s. As she looks back, that time appears remarkably tranquil to Olive, but she remembers how her mom feared for the future regardless and felt guilty for having children:

We want to believe that we’re uniquely important, that we’re living at the end of history, that now, after all these millennia of false alarms, now is finally the worst that it’s ever been, that finally we have reached the end of the world.

The truth, Olive seems to say, is more nihilistic. We are small and lost in time. We are connected to the years, decades, and centuries ahead of us — responsible to them — but also utterly apart, tied to personal worlds that arise “one after another after another” only to fade out so gradually “that their loss was apparent only in retrospect.”

The imagined future presented here, like that of Station Eleven, offers a way to think about how people construct new worlds. This time around, though, Mandel seems particularly attuned to the risks of world building: its cold comforts, its destructive and corrosive consequences, and the way it can subsume individuals under grand, merciless visions of progress and history.

Mandel’s sensitivity may come from the fact that Sea of Tranquility — with its carefully interlinked plots — itself risks losing the individual in the narrative. The complexity of the structure suggests a world overflowing with meaning, in which every moment is part of a larger whole and where characters’ fates are locked in place.

If there is any comfort to be taken in such a world, it’s available only to those who control the story, not those trapped by it. Perhaps that’s why, while Mandel dutifully wraps up Sea of Tranquility ’s entwined arcs and polishes the timeline — occasionally by taking a few easy exits — she also leaves a corruption in the file. In the final pages, a vision, somewhere between nihilism and fatalism, shines through: That human activity can spark the unpredictable. That despite individuals “being a still point in the ceaseless rush,” their actions can disrupt the course of events and create something new. Something to disorient us. Something truly anomalous.

Tomas Hachard wrote the novel City in Flames.

Related Letters and Responses

Robert Girvan Toronto