Along with stakeholders from business, academia, and the public at large, employees of the Department of Foreign Affairs and International Trade (as it was then known) were invited to take part in a major policy review in 1994 and 1995. I volunteered. Over the course of several sessions, I heard many officers, especially younger ones, advocate for a stronger emphasis on Canadian values. Others asserted the importance of defending and projecting our interests abroad. Thus was displayed the policy spectrum that spans liberal idealism at one end and conservative realism at the other. Liberal idealists strive to remake or at least improve the world. But conservative realists shun rose-coloured glasses. Squinting in the bright sunlight, they watch for trouble and are diligently wary. In Harper’s World, a rich essay collection on the foreign policy of Stephen Harper’s government between 2006 and 2015, the Queen’s University professor emeritus Kim Richard Nossal conducts a brief survey of such conservative realism.

Realism, Nossal argues, is sustained by an underlying pessimism. “A conservative expects the future to look not very different from the past, and is sceptical of utopian claims that humankind can rid itself of the scourge of war,” he writes, citing a Reagan-era United States ambassador to the United Nations, Jeane Kirkpatrick. Nossal also quotes the American neo-conservative William Kristol, who argued that foreign policy must be founded on “the natural and healthy sentiment” of patriotism and that international institutions that constrain a country’s actions “should be regarded with the deepest suspicion.” Leaders must also “distinguish friends from enemies,” a view derived, according to other commentators, from a “conviction that the human condition is defined as a choice between good and evil.” A keystone in this mindset is that countries primarily ought to pursue interests, not values.

In such views lay the ideological underpinnings of Harper’s foreign policy. As prime minister, he explicitly aimed to do there what he wished to do elsewhere: to engineer a fundamental change in how Canadians view the world. He wanted to shift our political reflexes from, as he saw it, soft liberalism to hard conservatism; foreign policy was one of the stages where he would attempt that. “If you’re really serious about making transformation,” Harper famously told the journalist Paul Wells, “you have to pull the centre of the political spectrum toward conservatism.”

Elsewhere in Harper’s World, the University of Prince Edward Island’s Peter McKenna, who also edited the collection, observes that the prime minister’s path led through “a relatively small number of core ideas . . . such as an interest-based foreign policy, a sceptical approach to the value of multilateralism, a beefed up Canadian military, expanding free trade, and strengthening relations with key Western allies like the US, the UK, and Australia.” The program that emerged following Harper’s minority victory in 2006 certainly reflected what might be expected from a conservative realist approach. Its primary initiatives were bolstering the military deployment in Afghanistan, an Arctic strategy that put greater stress on defence, an early softwood lumber agreement with Washington, an emphasis on and acceleration of negotiations for free trade agreements, an effort to articulate a so‑called Americas Strategy, and more enthusiastic support for Israel.

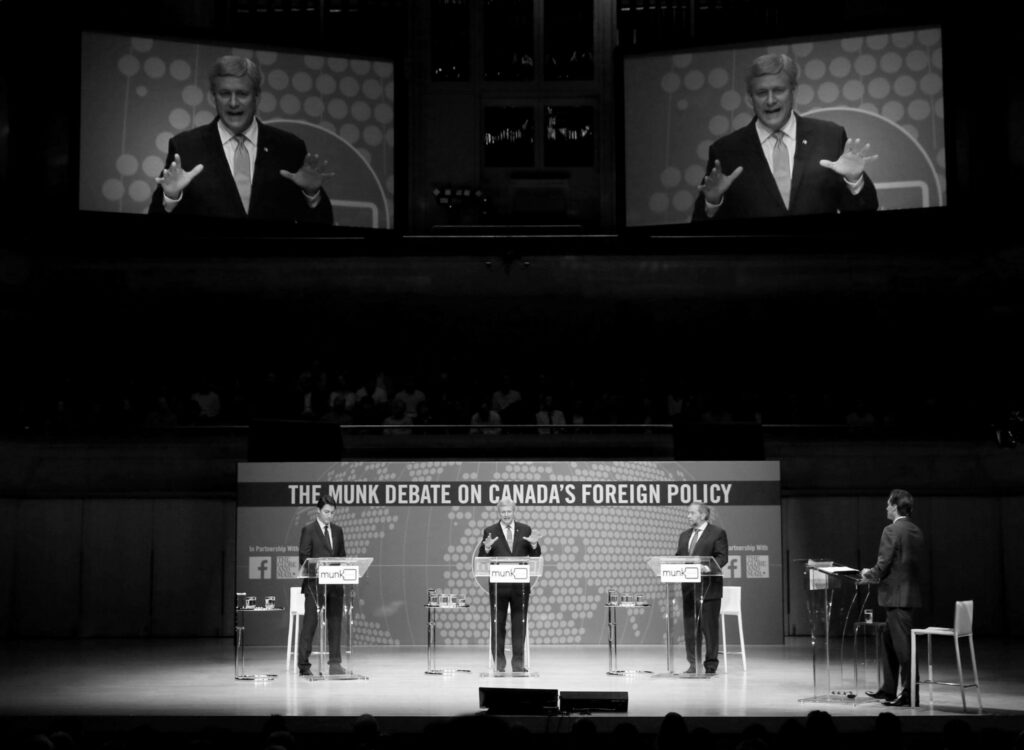

Different approaches to the world stage.

REUTERS; Alamy

These initiatives did not include a vision of Canada as a proverbial “honest broker” or “helpful fixer” devoted to international cooperation and the drafting of ambitious conventions on such things as arms control, the environment, or human security — and definitely not to cultural exchanges that would enhance Canada’s international “brand.” I learned of the disregard some had for conventional diplomacy directly, when the office of John Baird, the foreign minister at the time, castigated an event my colleagues and I had organized — bringing South African and Canadian authorities together to discuss a struggling bilateral relationship — as “a talking shop.” Harper’s scorn for diplomatic log-rolling at the UN and other international forums was summed up in his inimitable phrase “not going along to get along.”

Realism does not encompass the entire spectrum of conservative approaches to foreign policy. Another strain, not much in vogue, emphasizes the word’s derivation from “to conserve.” In the tradition of Edmund Burke, such conservatives stress the importance of the past and those elements of the social order that have led to peace and stability. What has succeeded should not be capriciously tampered with, and prudence should be exercised when bringing in reforms, lest they give rise to unintended and negative consequences. But when the old order is despised — when in Harper’s case Canada’s foreign policy past is not revered but rather anathematized as “Pearsonian”— Burkean restraint is not on the menu.

As steeped in conservative realism as many of the Harper government’s instincts were, its actions were not always grounded in it. In this contrast, we see the inevitable dissolution of certain ideals before the pragmatic task of governing; these compromises seem greater given how stern Harper’s instincts were. His initial enthusiasm for the mission in Afghanistan, for instance, diminished as he recognized that the prospect of more deaths among the Canadian Armed Forces — beyond the tragedy of 150 lives already lost — was an electoral liability. And Ottawa’s policy toward China was eventually marooned between two realist poles: opposing the ambitions of an authoritarian state, on one hand, and seeking stronger trade and investment ties, on the other.

As the University of British Columbia’s Paul Evans points out in Harper’s World, the decision to subject the investments of foreign state-owned enterprises to review was a clear concession to public concern about China becoming too powerful within our economy. And though good relations with the U.S. were central to the conservative realist handbook, Duane Bratt, of Mount Royal University, argues this objective fell victim to Harper’s effort to reassure Western Canadian oil and gas interests. After the prime minister asserted that Barack Obama’s approval of the Keystone XL pipeline would be a “no‑brainer,” relations with Washington soured — so much so that the Prime Minister’s Office forbade ministers from speaking with the U.S. ambassador in Ottawa.

As the above examples suggest, conservative realism was often stymied by the tyranny of events in conjunction with what Nossal calls “the primacy of the ballot box.” Ideological zeal was one thing, but Harper was eventually driven, several of the book’s contributors argue, more by his partisan ambition of trying to entrench the Conservatives as Canada’s “natural governing party.” Ideological and partisan considerations may be related, but they are not the same. Political pragmatism, focused on future electoral success, diluted philosophical convictions.

Harper’s Conservative Party did not arrive in power with a fully articulated foreign policy. But if his political colleagues lacked a detailed program for the Department of Foreign Affairs and International Trade, they did have aggressive energy and a good deal of attitude. New governments are right to regard giant bureaucracies with a degree of skepticism, but Harper’s hardly disguised its disdain.

McKenna offers a scathing account of relations between political staff and departmental civil servants. Following numerous interviews with senior officials, he outlines a litany of dismissiveness and abuse. Normal hierarchies were overturned; young political staffers issued orders to junior foreign service officers, bypassing the department’s civil service management, including, foremost, the deputy minister. Public communications, never easily generated and delivered by a media-wary department, were gagged by an insistence on long, torturous development of “message event proposals.” Programs typically managed by branches or missions had to be submitted to ministers’ staff for approval and then were left untended.

In 2007 and 2008, I attended several managerial meetings with Len Edwards, then the deputy minister, who spoke of his efforts to assuage “the centre’s” hostility (the centre being the PMO and its supporting officialdom in the Privy Council Office and the Treasury Board). Edwards, a seasoned senior official and diplomat, was intent on improving the department’s score in its official performance reviews. He also launched the “Transition Agenda” to show that the department was prepared to forge new approaches. He was more than willing to display good faith, but his political audience was reticent. McKenna quotes Peter Boehm, now a senator but previously a deputy minister, who experienced something similar. “So for 10 years, anything that the foreign service was doing was suppressed in our country,” Boehm said at a 2018 panel. “Part of what we need to do is provide fearless policy advice and loyal implementation and we had lost the capacity. Those muscles, those policy muscles had atrophied to a degree.”

There were exceptions. The government’s Americas Strategy stood out for genuinely articulating a program in cooperation — rather than in combat — with foreign affairs officials. It may also have been the most successful effort to convert the department’s orientation from liberal to conservative internationalism. Harper’s World includes a joint essay by the political scientists Jean-Philippe Thérien, Gordon Mace, and Hugo Lavoie-Deslongchamps, who argue that the decision to set the Americas as a priority reflected the influence of a “corporate constituency” of active Canadian investors; the desire to differentiate his government from the Liberals, who had focused more on Africa; and discussions with Australia’s prime minister, John Howard, about his country’s efforts to wield influence in its own geographic “backyard” of Southeast Asia.

In 2009, after three years of work, the veteran diplomat Alexandra Bugailiskis, then the assistant deputy minister for Latin America and the Caribbean, produced Canada and the Americas: Priorities and Progress, a strategy paper that emphasized the economic dimension of Canadian relations with the region: how to strengthen existing trade agreements, how to negotiate new ones, and how to capitalize on them with more vigorous trade promotion. These recommendations, it must be said, did not have to be extracted from a reluctant bureaucracy. Trade policy and promotion have always been key components of our foreign policy, and the department is flush with expertise. Arriving at the Americas Strategy was like pushing on an open door. And it makes one wonder how much more successful Harper’s efforts would have been in other areas had he better appreciated what the department was able to deliver.

Another recent collection of essays, Canada’s Past and Future in Latin America, comes to grips with the execution of the Americas Strategy and its fate following the election of Justin Trudeau’s Liberal government in 2015. For the most part, the contributors suggest that despite the avowed return to liberal internationalism, there has been no dramatic deviation in the current government’s approach. It has only slightly modified policies on corporate social responsibility for Canadian mining firms in the region, for example. There has been no change from the consensus that, as the University of Ottawa’s Paul Alexander Haslam describes it, “mining companies have a material interest in CSR policies that reduce social risk and the costs associated with it, including citizen blockades, destruction of property and violence, or drawing the disciplinary actions of political authorities.” The smooth sailing during the transition from Conservative to Liberal regimes suggests, in this instance, the virtue of that previously mentioned Burkean trait: respecting the past and showing prudence in introducing reforms. Some might argue that this continuity simply represents the inertia of moving systems, sometimes referred to as “path dependency.” But, as the axiom goes, “to govern is to choose.”

John W. Foster of the University of Regina contributes a fascinating essay on the Latin American Working Group, which had a profound impact on the Canadian mental map of the region over the course of five decades; he reminds us how homegrown intellectual movements have influenced government policy in the past. Founded as an association within the 1960s Christian youth movement, the LAWG developed into a research agency and think tank that increased public awareness of Latin America during an era of considerable ferment, including the Cuban Revolution, the military overthrow of Salvador Allende in Chile, the Argentine Dirty War, and civil wars in several Central American countries, along with the establishment of a more competitive democracy in Mexico. The urgency the working group brought to Latin American affairs coincided with a similar focus on Africa as it was decolonized in the ’50s and ’60s. Africa at that time “was a continent of vitality, growth, and boundless expectation,” Stephen Lewis wrote in 2005. “It got into your blood, your viscera, your heart.”

In another incisive essay on mental mapping, the Royal Military College of Canada historian Asa McKercher outlines the various narrative constructs that influenced, momentously at times, Ottawa’s stance toward Latin America. And Dalhousie’s David R. Black, in Harper’s World, suggests the fading away of that “Africa-affected generation” contributed to the Conservatives’ general indifference to sub-Saharan Africa.

A third collection, Middle Power in the Middle East, may sound a little conventional, evoking some shopworn platitudes. Seemingly not wanting to exaggerate the importance of their subject, the volume’s contributors describe Canada’s interests and relations in the Middle East as “modest.” But the essays themselves paint greater activity and urgency than that term implies. Indeed, enhancing international security and managing migration flows are hardly peripheral to our interests.

Middle Power in the Middle East makes slim reference to Canada’s groundbreaking peacekeeping achievement in the Suez Crisis in 1956, which used to be the touchstone for talking about Canadian policy in the region. September 11, 2001, is the key milestone here. Since then, army and police training programs in Iraq and Jordan, as well as the operation of our special forces against the Islamic State in Syria, have been significant undertakings. And although Trudeau withdrew air support in the fight against the Islamic State — to fulfill a 2015 campaign promise — he compensated for that by offering increased training of local forces. Once more, there is continuity between Conservative and Liberal governments. Harper did hesitate about welcoming Syrian refugees, while the Trudeau government distinguished itself by bringing in 40,000. Trudeau was cautious about repatriating citizens who went to fight for the Islamic State, but would Harper’s attitude have been any different? Where clear interests are at stake, policies can readily converge.

Nearly forty years ago, I had the rare opportunity to visit Al‑Safaa Square, in the heart of Riyadh, where public executions are carried out to this day. Scores of women clad in burkas, their faces hidden, their eyes obscured by narrow bands of mesh, tended the stores in the local souk. A Canadian embassy minder was suddenly agitated as he spotted a gowned religious policeman — a mutawa — walking through the crowd with his stick, ready to discipline dress violations or other infractions of sharia law. This was only one episode during a several-day stay in Saudi Arabia, which included an interview with the much adulated and outwardly modern Sheikh Yamani about his country’s role in the international oil market. But that day in the souk made the biggest impression.

I thought of my long-standing discomfort with the Saudi regime, as well as the more recent murder and dismemberment of the journalist Jamal Khashoggi inside his country’s embassy in Turkey, while reading the former political staffer Jennifer Pedersen’s essay in Middle Power in the Middle East, which delves into the Canadian government’s decision to green-light a $15-billion sale of light-armoured vehicles, or LAVs, to Saudi Arabia. The 2014 agreement was hailed as a huge success for both Ottawa’s embassy in Riyadh and the Canadian Trade Commissioner Service, which put considerable effort into securing the deal.

Saudi Arabia’s war in Yemen — a proxy conflict with Iran, which has sponsored a rebellion by Shia-faithful Houthis — started in 2015. As the fighting wore on, Canadian equipment started showing up on the battlefield. The LAV sale was initiated under Harper, Pedersen notes. “That the Trudeau government has continued to export arms to Saudi Arabia is not surprising.” She also cites the University of Ottawa professor Srdjan Vucetic, who “has argued there is little difference between Liberal and Conservative governments in exporting arms to human rights violators.”

Pedersen details a string of government evasions, excuses, and feeble correctives about the 2014 LAV deal, which involved General Dynamics Land Systems of Canada, in London, Ontario, as well as about other sales of armoured vehicles by Terradyne, in Newmarket, Ontario, and sniper rifles by PGW of Winnipeg. These weapons needed federal export licences, but it appears that in issuing them, Ottawa made a judgment that Riyadh’s war represents “legitimate security operations” with “appropriate” use of force. On balance, the interest in preserving thousands of Canadian jobs in a high-tech sector outweighed any effort to restrain the displacement and slaughter taking place in Yemen. Both Harper’s Conservatives and Trudeau’s Liberals made a Faustian bargain. Critics of the sales have argued that the horrible destruction wreaked so far conflicts with both Canada’s values and its interests, but they have not prevailed.

It is impossible to speak of Canada’s involvement in the Middle East, specifically, or Harper’s foreign policy, generally, without mentioning his extraordinary stance on Israel, which amounted to unswerving and wholly uncritical support. From 2009 to 2013, I was assigned as a political counsellor to the Canadian high commission in Pretoria, South Africa. At the time, billboards that displayed maps of Israeli settlements in the occupied territories were popping up throughout the city. They characterized the spread as a kind of apartheid — a debatable accusation that has since developed considerable potency.

Early in my posting, I received a call from my counterpart at the Israeli embassy, who expressed his strong appreciation for Harper’s unalloyed approval of his government’s actions. This was in the wake of one of several bombings of Hamas-dominated Gaza. “Your prime minister is even more supportive of Israel than most Israelis,” he said. I detected a certain amusement, a slightly suppressed chuckle. Indeed, in the vigorous public square of Israeli political life, criticism of the government and its policies is hardly infrequent, as a casual reading of Haaretz will show.

The Harper government did not change Canada’s official policy of opposing Israel’s occupation of the West Bank and of supporting the “two-state solution.” But the prime minister rarely spoke in favour of this policy, nor did he condemn the construction of more and more settlements in the occupied territories. Some argue that his objective was to attract the Jewish vote and to fortify the loyalty of Christian evangelicals. St. Thomas University’s Shaun Narine notes in Harper’s World that Jewish votes in key ridings did go to the Conservatives when they won their majority in 2011, although those ridings slipped away in 2015. Quoting Harper’s biographers, Narine argues that his fidelity to Israel was a personal position influenced by his father, a steadfast champion of the state’s establishment in the wake of the Holocaust.

Had Harper welcomed advice, he could have heard from some well-informed experts, including Michael Bell, who was at different times Canadian ambassador to Jordan, Egypt, and Israel (twice). In his final years, Bell was working through “track two” diplomacy to develop a model in which Palestinians and Israelis could share Jerusalem as a capital. This effort was just one diplomatic building block toward a possible solution.

What emerges from these three collections is that Stephen Harper’s government handicapped its own prospects for a successful conservative realist foreign policy through a lack of adequate policy preparation; a prideful assertion of principles somewhat removed from the actual practice of diplomacy; an irrational disparagement of civil servants and diplomats; and alienating posturing, especially but not exclusively concerning Israel.

Diplomacy is fundamentally a conservative calling — in the traditional sense of relying on well-honed formulas, carefully crafted communications, and time-tested protocols. But with mastery of the discipline, diplomats can also advance national interests in innovative ways. Should a Conservative government return to power, it would be best advised to temper populist ardour against international “elites,” including Canada’s own diplomats. It should focus on Canadian interests, yes, and recognize that it is wise to build the future on a solid appreciation of the successes of the past.

Geoff White served as a diplomat for nearly thirty years, a period he describes in his new book, Working for Canada.