In most cases, an immigrant chooses Canada more than Canada chooses the immigrant. Accordingly, the newcomer has the right to be critical of any national myth, not simply to lament or denigrate but to help make things better. Far too often, though, immigrants are expected to be grateful. They’re admonished, sometimes vehemently, for any criticism they make — political, cultural, and, perhaps especially, literary. I kept this in mind when reading two vastly different books by authors who chose this place.

Lydia Perović came here from Montenegro in 1999. She was escaping from wars in the Western Balkans, while also “searching for freedom: from family, ethnicity, nation, gender, poverty, an authoritarian political culture, an economy of the early accumulation of capital.” In Canada, she sought a liberal democracy, “only to learn that the project is never complete, and that one can never relax and return to private life, taking various freedoms for granted. That the wild orchids often have to wait.”

Having now lived here for more than two decades, Perović describes Canada as “the country that doesn’t quite gel,” in part because it “is decentralized into smithereens and interrupted with enormous empty spaces, none of which particularly disturbs it.” Put aside her shaky grammar, broken-back syntax, and other literary infelicities, as well as her brief play on Inferno (“Or to give my own riff on Dante, after twenty uncomplicated years of living as an adopted Canadian, I find myself in a dark forest, for the belonging is lost”). Perović decries how bad things have become, particularly over the past five years, with the heads of Canadian cultural institutions and media organizations putting “all of their chips on irreconcilable differences.” As she sees it, “there is no Canada for all, no political cause for all, and no arts for all. There is no individual outside ethnic determinism: there are bits and bobs of inter-regional and inter-ethnic resentment.”

This attitude she finds shocking compared with Canada’s formerly “declared agnosticism about blood and belonging”— promulgated by Pierre Elliott Trudeau — which was derived from the Enlightenment, though “a rather Victorian” strain had developed by 1967. In fact, her first class at Dalhousie University was “Liberalism and Democracy,” where the students who debated competing political visions and historical interpretations did so as “a matter of discussion” rather than “a matter of life and death.” Eager to “abandon blind obedience to traditions” by re-examining her life and becoming part of a new society “based on shared ideals and the conscious choice to belong,” Perović nonetheless discovered in Halifax that what sounded alluring on paper was far less fulfilling in reality.

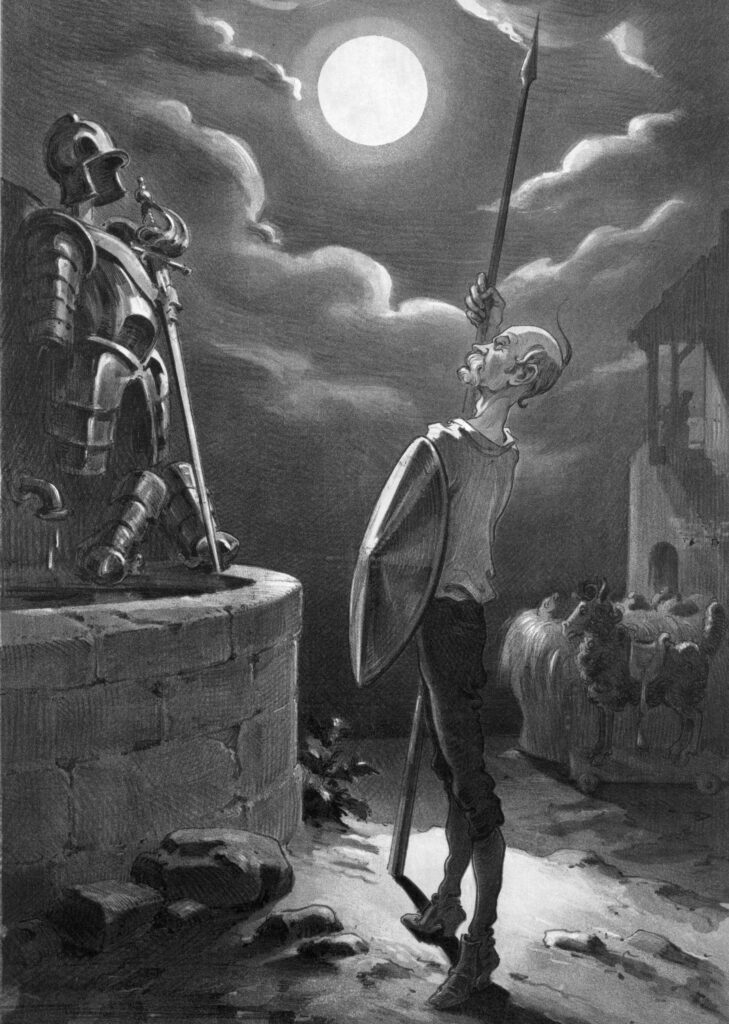

With long lance in hand.

Udo J. Keppler, 1905; Puck ; Library of Congress

Perović wrote her master’s thesis on Michel Foucault, that critic of liberal democracies, and while her academic bona fides are strong, she is so much in love with political theory (invoking the likes of James Tully, Janet Ajzenstat, and Richard Rorty) and categories (discussing the left and right and centre, the romantics and the liberals, the Gemeinschaft and the Gesellschaft) that much of her book reads like a rambling lecture. This is especially true of the first third.

As it mixes empirical evidence, anecdote, biography, and a potted cultural history of the Balkans and its literature of witness, Lost in Canada: An Immigrant’s Second Thoughts has flashes of insight, but as a whole it is heavily uneven and too often given to oversimplified generalizations. Consider the author’s complaints about North American mainstream activist feminism, the settler/Indigenous dichotomy, and the lack of a “Gaia-rific” lifestyle in Toronto, where she now lives. There is truth in many of her viewpoints, especially in her attacks on the woke rapture around cultural appropriation, the economic exploitation of unpaid volunteers and interns, the abolition of critical standards and arts coverage in the media, and “the tabulating of ethnicities in an artistic creation” in the larger “Canadian art conversation.” At this point, who could justifiably object to her view that our daily rituals of land acknowledgements “do nothing to improve actual Indigenous lives”? (As the Anishinaabe scholar Hayden King put it back in 2019, “I started to see how the territorial acknowledgement could become very superficial and also how it sort of fetishizes these actual tangible, concrete treaties.”) And Perović certainly hits the target when she claims that “Canadian multiculturalism, an idea we are proud of, in fact functions as widespread mutual indifference.” Hers is an immigrant story of radical disillusionment — perhaps an inevitability when idealistic yearning is eventually mugged by reality.

Her principal argument suffers from its digressions (including one on traffic hazards and the urban cyclist) and, especially, from a relentless quest for significance. While she points to the lack of content in Toronto concerts and operas, she does not discuss the art or craft of any poem, story, or novel. Clearly, she’s more interested in the “pragmatics of the work” than in the techniques of creation. She wants intellectual activity that resonates “in the history of the human struggle for justice.” Yet, for me, the most cutting and provocative sentence in her entire book is this: “Should a culturally curious tourist land in Canada in 2022 and open a daily paper or turn to the national broadcaster, she will conclude that Canada has little in the way of live arts and no national culture.”

I do not know if Perović has read much by her fellow immigrant John Metcalf, but she should. Her vehement railing against funding organizations — for promoting “representation, relevance, reconciliation, decolonization, queering (a word that means everything and nothing these days), community, respect, healing, equity” at the cost of artistic excellence — certainly intersects with Metcalf’s incandescent attack on the enemies of aesthetic standards. That said, I doubt that Metcalf would enjoy reading Perović, because pragmatic significance and sincerity mean relatively little to him as a self-professed proselytizer for prose. In fussing over the execution of style, Metcalf honours Oscar Wilde’s dictum that “everything matters in art except the subject.”

Quill & Quire has described Metcalf as an “editor, teacher, author, critic, and pioneering anthologist of Canadian fiction.” He is also a persistent thorn in many an ultranationalist’s side for his criticism of Canadian writing as well as of Canadian culture in general. An inveterate formalist, he possesses an ornate style and makes magisterial pronouncements that are steeped in acid wit and that infuriate those who cannot abide his sharp critiques. But these opponents hardly deter Metcalf. A fine writer of short stories, he has edited more than 200 books over five decades, including eighteen volumes of Best Canadian Stories. His non-fiction collections include Kicking against the Pricks (pun intentional); What Is a Canadian Literature? ; Freedom from Culture ; and An Aesthetic Underground: A Literary Memoir. His titles alone give ample evidence of the role he chooses to play as an arbiter of literary taste and an uncompromising crusader.

Metcalf’s latest, Temerity & Gall, derives its title from the novelist W. P. Kinsella, who in a 1983 letter to the Globe and Mail railed that “Mr. Metcalf — an immigrant — continually and in the most galling manner has the temerity to preach to Canadians about their own literature.” An Englishman by birth, Metcalf allowed his delight in this uproarious bluster to marinate for almost forty years before constructing a hefty response. The cover features an ink sketch of Don Quixote, long lance in hand, mounted on his skinny nag, Rocinante. But Metcalf declares in one of several engaging exchanges with his editor and publisher, Dan Wells, that he really isn’t “a Don Quixote unsteady in the saddle, bereft of brain.”

Temerity & Gall is a deeply idiosyncratic hybrid of memoir, meditation, apologia, criticism, and satire. Loosely, it covers Metcalf’s literary enterprises in Montreal, Toronto, and Ottawa, which each played host to a 2015 national tour by the former Montreal Story Tellers. Joining Metcalf back then was Ray Smith, morose and rather remote, and Clark Blaise, who was ailing. (Two of the original five Story Tellers were missing. Hugh Hood had died in 2000, and Ray Fraser was excluded.) The reunion tour lends itself to some colourful satiric narration, though this part of the book is rather uneven structurally.

Despite Metcalf’s objections to the contrary, he does often appear to be “waving a sword about and shouting threats at an encamped army” of all sorts of “drongoes” (his word). He takes on, for example, canon-feeding academics, the frothing, hooting “go-back-to-where-you-came-from brigade,” the pooh‑bahs at the Canada Council (particularly its CEO, Simon Brault), the CBC (“a national embarrassment culturally speaking”), and Justin Trudeau (“merely a willy, a bad actor eager for photo ops”), among others. While his rhetoric is characteristically eloquent — with every word apparently a mot juste — and the main thrust of his screed justifiable, his general arguments and tangential opinions sometimes seem futile, stale, and unprofitable.

Yet these windmill arms stir quite a breeze. In his first forty-seven pages alone, Metcalf scorns not only Ray Fraser for being “flushed, fumbling, and crude” but all the following: Jack McClelland, for publishing fiction and poetry that now seem “moribund, decaying down into literature’s leafmold, doomed to dutiful mention in dusty literary compendia”; Matt Cohen, for “pseudo-lyrical verbiage”; Leonard Cohen, for poetry that’s “exactly right for the twelve-to-sixteen-year-old ‘naughty set’ ”; Anna Porter, for rejecting a brilliant Clark Blaise short story collection, “almost by return mail, with a dismissive note”; Brad Martin, the former CEO of Penguin Random House (Canada), for not being interested “in a book that is going to generate less than $100,000 in revenue”; David Staines, for declaring that Morley Callaghan is a better writer than Ernest Hemingway; Margaret Atwood, for her “political claptrap and bubblegum psychology”; Michael Ondaatje, for writing that has “ripened into arteriosclerosis, dangerously florid”; Jane Urquhart, for her “string of potboilers . . . resolutely middle-brow”; and the “vegetable” known as the Writers’ Union of Canada, “doomed to grow, as I suspected it would, ‘vaster than empires.’ ”

To be sure, Metcalf does raise important points. “Are we inheriting our past?” he asks Wells in one of the editorial asides printed in the book. “Are past and present a continuum? Because that is essentially what ‘a literature’ is. And by that definition I fear we’re in desperate straits.” Even the dry stuff of his argument matters a great deal: “If we declare, as we do, Morley Callaghan a ‘classic,’ how do we simultaneously accord the same status to Alice Munro? And, more vitally, vice‑versa? If we adjudge the short stories of Sinclair Ross and Margaret Laurence as ‘classic,’ what can we meaningfully say of the stories of Mavis Gallant? And vice‑versa.” Whereas Atwood rewrote history with Survival, by implying that “the Canadian literary past had meaning and coherence and value as a literature, as a coherent developing force, that these random colonial drearies were our literary ancestors,” Metcalf wants to “rewrite the rewriting, trying thereby to more accurately retrieve the past, to counter lunatic judgements, and to make contemporary judgement more possible, more credible.” But even Wells protests that part of Metcalf’s argument seems “so static, revelling too much in an exaggerated failure. As if nothing has changed since the mid-80s. . . . These are old battles.” Touché. “The issues we face are different now,” Wells continues. “The pressures threatening our literature have little to do with nationalist short-sightedness. It’s connected to global economies and what people term neoliberal politics. Where our small markets are swamped by international offerings, most of them bad, and our media are owned by Wall Street hedge funds. And, yes, cultural bureaucrats who believe innovation comes via microchips.”

It may be the height of my own temerity and gall, but I contend that, despite Metcalf’s indisputable expertise as editor, this book needed an outside eye or that Wells needed to more ruthlessly wield the delete key. At the very least, Wells could have continued with his sober editorial rebuttals or challenges throughout the massive text; they die off rather prematurely.

That’s not to say there’s anything flawed in Metcalf’s diction or syntax or in the heart of his chivalric mission, which is to bear forward the oriflamme of the best Canadian writers. But where is Wells’s astute editing when Metcalf repeatedly overindulges in massive quotations from his own previously published polemics? Moreover, Temerity & Gall is heavily larded with quotations from Ronald Firbank, Osbert Sitwell (on Firbank), Beryl Bainbridge, John Banville, Cyril Connolly, Ernest Hemingway, John Cheever and Malcolm Cowley (on Hemingway), Samuel Beckett, Robert Hughes, Walter Pater, Evelyn Waugh, Clive James (on Waugh), Anthony Burgess, Kingsley Amis, et cetera. Yes, they’re all on point, but many of Metcalf’s comments about literary texture and technique could have been made with references to Blaise, Hood, Munro, Gallant, Norman Levine, or some of the outstanding short story writers he has edited, including Caroline Adderson, Keath Fraser, K. D. Miller, Steven Heighton, and others he has proudly watched move “from gumboots to accomplishment and sophistication.”

All these exercises — including a roll call of Metcalf’s reading and a catalogue of rare-book acquisitions, with prices, of course — turn Temerity & Gall into a long-winded compendium of digressions and superfluous amplifications, as when he repeats some of Maurice Bowra’s bons mots (“Buggery was invented to fill that awkward hour between Evensong and cocktails”); when he quotes Vita Sackville-West on Lady Ottoline Morrell (“with masses of purple hair, a deep voice, teeth like a piano keyboard and the most extraordinary assortment of clothes, hung with barbaric necklaces”); or when he uses the words of Auberon Waugh to flay Anthony Powell (“If I decline to discuss Powell as a literary phenomenon, out of priggish fastidiousness about his abominable English . . .”).

While many of the digressions are delightfully droll, others are simply expendable. As a devotee of Cyril Connolly’s famous dictum “An expert should be able to tell a carpet by one skein of it; a vintage by rinsing a glassful round his mouth,” did Metcalf really need to quote from Gao Xingjian’s Nobel Prize acceptance speech to make the point that the criterion of merit ought to be aesthetic quality, not social fashion or an embellishment for authority? As he has shown many times through close textual analysis (especially of Munro’s short stories), Metcalf hardly needs other thinkers to buttress his arguments or support his fascination with those in his personal pantheon of talent. And when he sticks to his own writing life, he is excellent, declaring that he has been in “a constant conversation with Imagism.” Sadly, though, this book leaves a devastating image of Metcalf setting off alarms in all directions, without evident concern for a sympathetic reader.

The satiric narrative portion of Temerity & Gall concludes in Ottawa, where Clark Blaise looked and sounded like “a runner, far behind the competition, gamely struggling on alone to the finish line,” while Ray Smith awkwardly wrestled “to raise the height of the mike, words flubbed, apologies, rattling phlegm amplified, apologies. Small silences where he was obviously deleting sentences or paragraphs. All the rhythms off.” Metcalf, for his part, was lugging some books around in boxes.

The scene will be familiar to most Canadian writers, because the real work of our literature is to keep lugging those damned boxes to poorly attended readings, even if there are fewer and fewer of them by the day. If only Metcalf had offered more of his narrative and less of his amplified digressions. In other words, at half its present length, this book would have had twice the clarity and power.

Keith Garebian has just published his eleventh poetry collection, Three-Way Renegade, as well as a memoir, Pieces of Myself.