You in Canada with all your reading of war. Those in America and England cannot realise at all what war is like — You must see it & live it — You must see the barren deserts war has made of once fertile country — see the ghastly shells of lovely towns, see the places where towns were — see the turned up graves, see the dead on the field, freakishly mutilated — headless, legless, stomachless, a perfect body and a passive face and a broken empty skull — see your own countrymen, unidentified, thrown into a cart, their coats over them, boys digging a grave in a land of yellowy green slimy mud & green pools of water under a weeping sky. You must have heard the screeching shells and have the shrapnel fall round you, whistling by you — Seen the results of it seen scores of horses, bits of horses laying around, in the open — in the street and soldiers marching by these scenes as if they never knew of their presence — Until you’ve lived this little woman — you cannot know.

A. Y. Jackson neither painted as well as Thomson nor wrote as well as Varley. Although he no doubt burned the letters he received in his stove, along with hundreds of his own paintings, his family and friends, luckily, did not do likewise. His surviving written record is astounding. The art historian Naomi Jackson Groves — his niece — helped ensure that this material was recognized and safeguarded in a number of archives in Canada. Both she and Jackson himself relied on it to produce, in his case, an autobiography and, in hers, several publications. Following Jackson’s death, Groves also took care that his surviving work was documented and that his sketches were appropriately housed. It is hard not to be overwhelmed by the Jackson archival cornucopia that is so well preserved. (I say this as someone who also is writing about the Group of Seven’s relationship with war.)

From this documentary feast, Douglas Hunter has written a remarkably engaging account of the artist’s first forty years or so. Only halfway through Jackson’s Wars: A. Y. Jackson, the Birth of the Group of Seven, and the Great War, however, does Hunter stop inserting his own voice, analysis, and interpretation into the artist’s voluminous record — finally leaving his wartime words to stand for themselves, letter by letter.

Hunter explains that he has tidied up Jackson’s letters. Consequently, some of the breathless stream-of-consciousness effect common to Varley’s correspondence, which Jackson’s copious use of dashes also creates, is here controlled by periods, commas, question marks, and capitalization. Hopefully, another pandemic won’t close the archives again anytime soon, because if Jackson’s original letters are inaccessible in the future, any student of the artist will have to rely upon Hunter’s versions more often than not.

He returned to the front an officer.

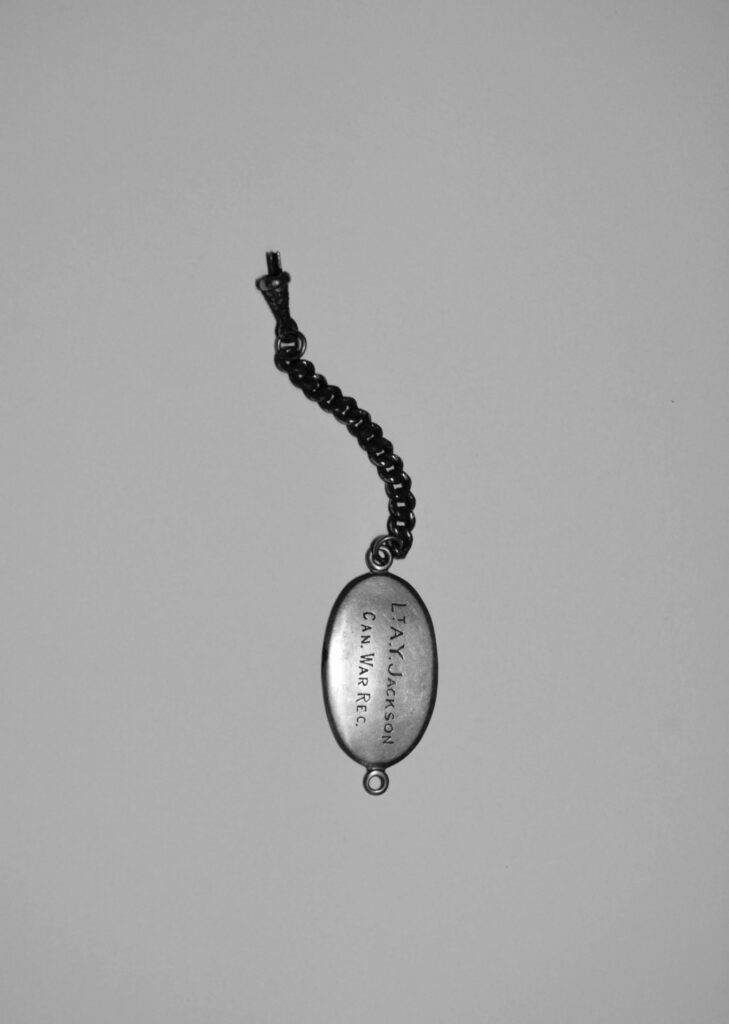

Canadian War Records Office; Courtesy of McGill-Queen’s University Press

The letters can be offensive, and Hunter points out the awful racism and terrible attitudes toward French Canadians, both of which suggest a sometimes unattractive character. But Jackson was unquestionably of his time, and herein lies the value of this book.

Most art historians — and many among the general public who appreciate art — can accept Jackson as a driving force in the history of Canadian art and a friend and supporter to many. Less well known is the socio-cultural milieu that formed this rather ordinary bachelor autodidact and commercial artist, who left school at the age of twelve. His stint painting the war and his own ambition catapulted him onto the national stage as an exemplar of artistic achievement. Hunter writes well about how Canadian artists evolved in a time when the homegrown product enjoyed only modest appeal with collectors. Instead, they relied on what were essentially amateur critics to take note of their work, for better or for worse, in the annual exhibitions put on by civic art institutions and associations.

In his introduction, Hunter argues that we need to know this period, which many writers, perhaps including Jackson himself, have short-changed. In his opinion, it forms the bedrock upon which the Group of Seven monopoly of Canadian art was built. But we also need to be careful not to overemphasize this early period’s importance to the bigger picture.

Although the archive of Jackson’s first forty years is of interest for a number of reasons, it hardly represents the full story. Yes, from his letters and other writings from this time, we learn much about his life in Montreal, his innumerable relatives, his unconsummated love affairs, his time in Europe, his notable friendships and alliances, and his determination to put Canadian art on the map. We also learn about his own work as he sought new ways to depict the Canadian landscape, having judged the earlier work of others to be inadequate. And we learn about his First World War experiences and paintings. But because Hunter’s book ends just after the armistice, we do not learn here about what happens next: the achievements, grit, and determination that collectively made Jackson the Grand Old Man of Canadian art.

A. Y. Jackson lived out his last years at what is now the McMichael Canadian Art Collection in the Humber River Valley in Kleinburg, Ontario, close to the graves of most of his fellow Group of Seven artists. He was trotted out on special occasions. This book assumes he is important — and he is — but without the next fifty years of his life in the picture, we do not fully understand why. Perhaps there will be a second volume?

Laura Brandon was the curator of war art at the Canadian War Museum for over twenty years.