So I continue to pace and dodge stacks of boxes. You might say, it’s not that I haven’t fully unpacked — but that I’m already halfway packed out. Weeks keep going by, and out of this in-between, paralyzed moment, the real stares back at me.

— Jake Marmer

My father’s years as a flight lieutenant in the Royal Canadian Air Force entailed family moves every two or three years. That meant arriving in a new neighbourhood and school, sometimes at mid-term, knowing nobody, learning the cliques of the base, finding whom to avoid and who might be a friend, however briefly. I loved this “gypsy life,” as my grandmother still called it, not least because each time we moved I got to unpack my stuff.

Slicing open cardboard box after cardboard box is not everybody’s idea of a good time, but when you have bundled your entire worldly existence into a few standard-size Allied Van Lines cartons, leaving out only your clothes for the motel stays that separate you from a new house (sometimes with the same floor plan as the old one, just way across the country), reopening them is a kind of rebirth, a miracle of possibility. As I got older, the contents shifted from Lego and plastic ray guns to fighter plane scale models and then, finally, to books.

I had a shelving system of sorts that lived in at least six different locations, including three during my undergraduate years. It was fashioned of black pine boards and stacked columns of red bricks, with corrugated edges and three holes each. (The fine ochre dust from the bricks would always settle onto the books.) I can feel still the muscle memory of reassembling this makeshift yet surprisingly long-lived piece of furniture. Then I would open my boxes, deposited in the room by the overalls-clad movers, with an irrational sense of wonder and anticipation. I had packed my books away just two weeks earlier. They hadn’t changed.

The material logic of book collecting.

Jamie Bennett

But they had — because this was a new chapter for me, in a new setting, with new friends to meet. I would haul out with pleasure the large science omnibuses my mother liked to give me for Christmas, the stuff on aviation and football my father favoured, and the many, many Hardy Boys mysteries, with their bright blue spines, passed down from my older brother. Later, independently wealthy in scant adolescent fashion, I would hoard my allowance money to buy boxed sets of The Chronicles of Narnia, The Lord of the Rings, and the Earthsea and Dune books, works by Robert A. Heinlein, Ray Bradbury, Kurt Vonnegut, Anne McCaffrey, Isaac Asimov, Philip K. Dick, and Fritz Leiber, or anything with a cover illustration by the Brothers Hildebrandt or Frank Frazetta. (I admit to some of Robert E. Howard’s deplorable Conan the Barbarian stories in there, too.) Later still, I added works by Bertrand Russell, Carl Sagan, and Fritjof Capra.

It didn’t take me long to begin a years-long pilfering of my father’s Book of the Month Club selections in the living room. There I found many treasures: C. S. Lewis’s The Screwtape Letters, Jean-Paul Sartre’s No Exit (mind blown!), José Ortega y Gasset’s The Revolt of the Masses (ditto!), G. K. Chesterton’s The Man Who Was Thursday (awesome), Ernest Hemingway’s A Moveable Feast (life lessons, sort of), and William L. Shirer’s The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich (riveting and my favourite history book until I read John Lukacs’s Five Days in London many years later).

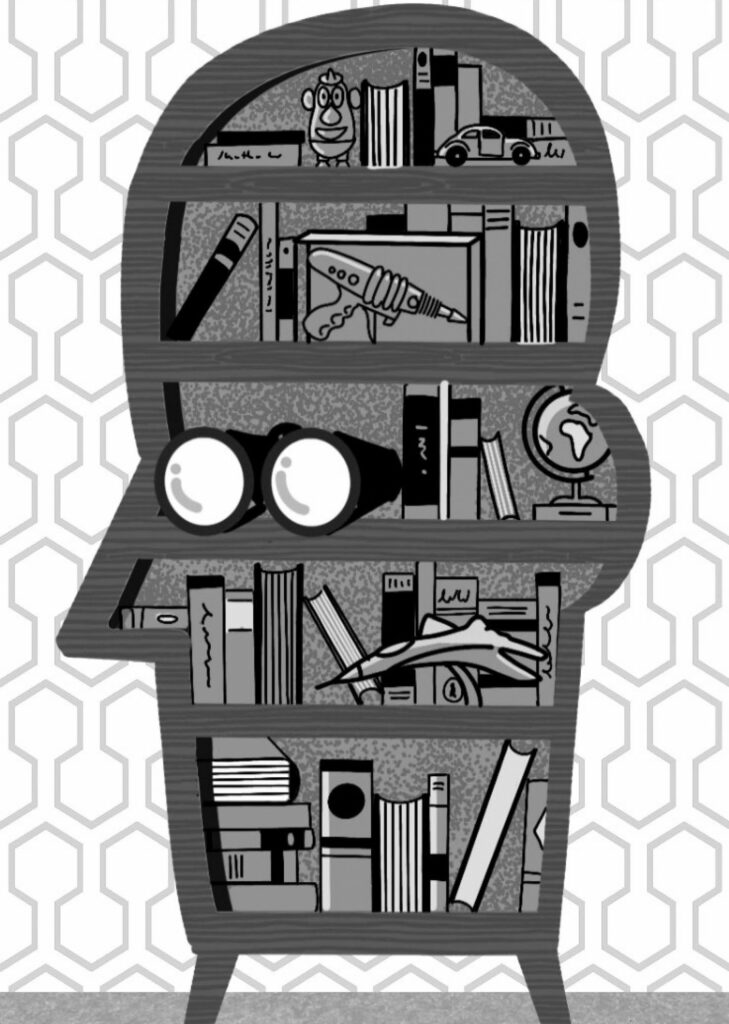

I still have those last titles, all hardy veterans of various moves. I likewise retain my science fiction and fantasy boxed sets. But the rest are gone or, in rare cases, replaced. (Russell’s popular works, especially Has Man a Future?, The Conquest of Happiness, and The Problems of Philosophy, are minor-key masterpieces that should be on every bookshelf.) I have never stopped buying books, though, mostly in used bookstores. Sometimes, I like to think of myself as a librarian to myself, curating an idiosyncratic and rotating index of works from every stage of my reading life. I suspect many bibliophiles are like me. I have some valuable editions, but the largest chunk by number are orange Penguin paperbacks, surely the perfection in English publishing of the genuine livre de poche. There is no rhyme, reason, or order to — and certainly no catalogue raisonné for — my eccentric and now decades-long acquisition of codices. There is only me. Or rather, I should say, they are only me, and I them.

A haphazard collection of books is more interesting, and revealing, than an ordered one. The poet Donald Hall, a personal favourite of mine, talked of what our books say about us in Unpacking the Boxes: A Memoir of a Life in Poetry. I also like Unpacking My Library: Writers and Their Books, in which Leah Price interviewed a number of contemporary writers, including Junot Díaz, Claire Messud, Philip Pullman, and Edmund White. I particularly enjoy two quotations from this mostly unsurprising volume. Jonathan Lethem: “I hate lending, or borrowing — if you want me to read a book, tell me about it, or buy me a copy outright. Your loaned edition sits in my house like a real grievance.” And Alison Bechdel: “I do lend my books out, but I have to be a bit selective because my marginalia are so incriminating.” I also appreciate this morsel from Price’s informative introduction: “A self without a shelf remains cryptic; a home without books naked.”

That sentiment is widely held among dedicated readers and writers; it forms the basis of the material logic behind book collecting, both private and public. To unpack even one box of books is to invoke a scattered community of the literate and word-hungry. Susan Orlean, Matthew Battles, and others have written movingly about the importance of libraries as public trusts, refuges, bastions of democracy, and examples of jaw-dropping architecture. They are all of those, and more. I love libraries, indeed have spent large chunks of my life in them, from nondescript military-base sheds, one step up from Quonset huts, where I did my homework and read Tintin and Astérix adventures in French, to the Sterling Memorial at Yale and the Wren at Trinity College, Cambridge, as well as the underappreciated Caven Library, Knox College, and the Hart House Library, both at the University of Toronto.

A personal library is different, however. It lives and evolves over time, it reflects you and your mortal span, maybe even casts a gimlet eye over who you are becoming or once were. (Again, those Conan books . . .) Unpacking, then, is a kind of psychic spelunking or archeology: thrilling but also uncertain and potentially dangerous. Did I really like that Kingsley Amis so much that it survived multiple trips in and out of cardboard? I guess I did.

Perhaps the most famous account of this material exercise in self-reflection comes in Walter Benjamin’s “Unpacking My Library,” that charming and poignant essay from 1931. Here are its opening sentences, rendered in excellent English by Harry Zohn: “I am unpacking my library. Yes, I am. The books are not yet on the shelves, not yet touched by the mild boredom of order. I cannot march up and down their ranks to pass them in review before a friendly audience. You need not fear any of that.”

The activity is solitary, but the effect is communal — after the fashion of all personal writing. Benjamin continues: “I must ask you to join me in the disorder of crates that have been wrenched open, the air saturated with the dust of wood, the floor covered with torn paper, to join me among piles of volumes that are seeing daylight again after two years of darkness, so that you may be ready to share with me a bit of the mood.”

And what mood is that? Not an elegiac one, but “one of anticipation which these books arouse in a genuine collector. For such a man is speaking to you, and on closer scrutiny he proves to be speaking only about himself.”

Unlike Benjamin, I am not a “genuine collector”— just a lovestruck and semi-random one. But I waited more than a half-dozen years to rescue my own library from the boxed darkness of a basement, and I know that mood of anticipation well. I have different shelves now, and they stand ready to welcome their future inhabitants with open arms.

When I got married in 2008, I was living in, or anyway still paying rent on, a nice one-bedroom apartment in Toronto’s Seaton Village. I had moved there with my first wife in 1991, right after graduate school in Scotland and Connecticut. Two decades gave me time enough to pack the place with books and ephemera. This was different than all those previous moves. Even when I went to Edinburgh in 1985, I schlepped just a few books in my rucksack and convinced some friends to pack a few more in exchange for a sleeping bag on the floor and a pint or two; when I shifted domicile to New Haven a couple of years later, I bought an old-fashioned shipping trunk and sent all my books by ocean freight. Lifting its lid, when it finally arrived, was a joyful moment.

Now I had the chance, even in a rental space, to really dig in. Maybe my human hunker-down instincts were finally taking over? Regardless, my craving to buy and keep books only intensified after my divorce, when I had the apartment to myself. I bought history and philosophy, poetry anthologies, hot-off-the-press fiction — a new indulgence after years of waiting for paperbacks or (sorry, fellow authors) remaindered hardcovers. The place never became an outright rat’s nest, but the books piled high after they outgrew the many IKEA shelves I assembled. They were stacked on the floors and dressers, arranged in piles for reference to one project or another, fighting for space on the bedroom floor and in the kitchen, and, eventually, overwhelming the front room until there was nowhere left to sit except my desk chair. Other collections grew alongside: Xbox games (a waist-high stack), fishing gear (thirteen fly rods and nine reels), sneakers (at least fifty pairs), and art (enough to fill all available wall space).

In 2017, after many jokes about the reality show Hoarders and admitting I hadn’t slept in the place for years, I finally decided to pull the plug on the apartment. But this meant I had to get my stuff out. I knew my spouse’s Cabbagetown place, a pretty but narrow red-brick semi, would burst with the volume. So began the Great Vermont Avenue Cull.

For almost a week, I went through all the books, articles, posters, pamphlets, and offprints I had acquired in what had seemed like quiet years — plus the video games, CDs, too-small suits, shoes I no longer wore, and bits of furniture. We filled the front lawn three times, asking nothing, and eventually every single item was carried off, to take up residence in someone else’s gaming room, closet, or personal library. I hope the books, especially, are happy and not bothered by being rejected.

Even with ruthless sorting — I hesitate to think what I gave away that I would like back — there were too many books for the Cabbagetown house. So cartons of them went into the basement, together with a dehumidifier to ward off rot. There they joined a jumble of sentimental but useless family heirlooms (a dollhouse, a rickety baby chair), random pieces of bad art, and my fishing equipment. I left the cartons stacked along one wall — until now. For the first time in decades, I am reliving that youthful experience, which can never get old, of unpacking my library.

What are the highlights on this most recent journey of self-rediscovery? For one thing, I’m struck by how much I associate certain books with where and how I bought them — and sometimes with whom. I found my first edition of Brideshead Revisited in a Toronto used bookstore. It was beyond my means, but my friend Matt Parfitt pressured me to splurge. (He and I were mesmerized at the time by the Jeremy Irons and Anthony Andrews television adaptation.) My copy of C. L. R. James’s Beyond a Boundary hails from Edinburgh, when I was on a cricket kick abetted by Mike Nash. A bunch of old etiquette manuals — Giovanni della Casa, Amy Vanderbilt, Emily Post — were all acquired in New Haven, when I was researching the history of manners and civility alongside my colleague Chris Dustin. (The Vanderbilt has commercial illustrations for place settings and the like by one “Andrew Warhol.”) A battered first edition of John Kenneth Galbraith’s The Affluent Society also dates from this period, coming highly recommended by Jodi Mikalachki.

There are dusty novels and poetry collections plucked from stalls along London streets and the Left Bank in Paris, and many espionage paperbacks come from high-piled shops in Sydney, Vancouver, and Toronto. I have Edward Goreys from Cape Cod, rescued gems from junk barns in New Hampshire (Stephen Leacock, Carl Van Vechten), and a twelve-volume hardcover edition of À la recherche du temps perdu, bought on a whim in a long-gone spot in Montreal. I found a nice hardcover collection of Hemingway’s Nick Adams stories at the same place and intended to give it to my father, but I didn’t. I cleaned out the English-language books in a Shanghai shop one year, mostly Philip K. Dick paperbacks. And when East Berlin was still a place, I exchanged some Bundesrepublik marks for GDR coins, light as tinfoil, so I could buy some hardcover editions of canonical Marxist-Leninist doctrine. (The rest went to gassy beer and mealy sausages for lunch.)

Other places, other moments, other languages: volumes from Zagreb, São Paulo, New York, Chicago, Berkeley, Saint John and St. John’s, Cleveland and Cincinnati, and so it goes. Because I keep the bulk of my philosophy texts at my university office — untouched and mostly unseen for the past two years, but nevertheless living in the open — these boxes I have lately come back to are dominated by fiction, mostly British, Canadian, and American. Lots of Evelyn Waugh and Graham Greene (two kinds of Catholic writer, one might say, stylistically and spiritually) and some undergraduate-inflected leftovers I couldn’t bear to lose: Norton anthologies, T. S. Eliot’s essays and poems, plenty of Yeats. There’s a John P. Marquand novel, once a massive bestseller that made its author a national celebrity, that hangs on to life here. I see some bell hooks and Alice Walker, some V. S. Naipaul, and James Baldwin’s The Devil Finds Work. Several underappreciated masters of style (Walker Percy, J. P. Donleavy, Morley Callaghan) sit next to the globally celebrated (Atwood, Bellow, DeLillo, Pynchon, Walcott).

I guess I really do like Kingsley Amis, because there are a fair number of his novels in Penguin orange, including the copy of Lucky Jim that I bought in Edinburgh during my first term there. What could have been better? Before public internet, I sat in my tiny room just off the Royal Mile and chortled at what remains the gold standard of academic satire. There are also some nasty early works by his son Martin, that writer of astonishing precocity, as well as some light but obscure favourites: lots of P. G. Wodehouse, mostly Jeeves and Wooster but also Laughing Gas. The well-known Nancy Mitford novels of love’s pursuit and cold climate are here in hardcover, alongside a cheap paperback of her frothy comedy Christmas Pudding, which I used to reread every year.

One other retrieval catches my eye: a four-volume (or “four-movement,” as the author styled it) set of A Dance to the Music of Time, Anthony Powell’s twelve-novel roman-fleuve. Memorably, it caught someone else’s eye once: that of Rex Murphy, now a right-wing goblin-columnist at the National Post, where he enjoys a popular following among those who like his opinions and tortured prose. When he was still with the CBC, Murphy (a very short man, with a large head) stood in my Seaton Village living room as we prepped for an interview I was about to do with him. He looked critically around the room, saying nothing, until he spotted the Powells. “Ah, very good,” he said. “You have taste.”

I’m not sure an interest in Anthony Powell counts as good taste, but as I lifted those four volumes into the light, I recalled the title of the tenth novel in his sprawling observation of British society: Books Do Furnish a Room. That they do, adding colour and life and also, less tangibly, a sense of connection to the wider world of culture and tradition. I think I like the title more than I like the story.

When I think about books and libraries, I often think of a thriller by Michael Innes, the pen name of the Scottish writer J. I. M. Stewart. In fact, I can once again see the 1951 novel from my desk. It is called Operation Pax in British editions but, for some reason, The Paper Thunderbolt in American ones and is the twelfth book to star the Metropolitan Police detective John Appleby. I’m pretty certain that I acquired my used Penguin paperback copy, with its green rather than orange spine, somewhere in Britain, maybe in Glasgow or Aberdeen, Leeds or York. No matter.

The quite preposterous plot involves a criminal conspiracy to brainwash the entire British population into non-resistant complacency prior to foreign conquest, and the passage I will never forget takes place at the Bodleian Library, where a con man has stashed the stolen formula for the brainwashing technique. It’s not in the above-ground stacks but rather in the cavernous storage spaces below ground. Here Appleby is confronted — and we readers with him — by literally millions of books, almost all of them long forgotten.

The real-life Bodleian boasts holdings of more than thirteen million volumes. Imagine the sense of futility, of human effort committed to paper bound for dust, that stands housed in those shelves. The good ideas that never caught on, the bogus philosophies and theories, the pet projects and vanity undertakings, even the thin slice of utmost human excellence that has simply fallen out of favour. It’s almost enough to make one quake with despair — and to throw all writing implements into the sea!

But not quite.

Words committed to paper, bound every which way, aged or brand new, affirm the human spirit and the often futile, irrational hopes of posterity. Books are pretty stable technology, needing only the software of literacy and some available light to function unimpaired almost forever. Benjamin, for one, could not live without them, but neither could he die without them by his side. Attempting safe passage to America through the Pyrenees, he was stalled at Portbou, in Catalonia. All travel visas were cancelled. At risk of being deported back to occupied France and his Gestapo hunters, he resorted to a desperate act: an overdose of morphine tablets. According to some sources, in the suitcase he was carrying lay the sprawling manuscript of his masterpiece, The Arcades Project.

Opening one last carton, I come across an English translation of that forever unfinished masterwork of philosophical invention. To create genius from adversity is a form of courage beyond reckoning. Every volume we have, down to the lowliest trashy paperback, is a testament to human will and our uneasy relations with mortality and the real.

Books will not save us. But let them find space on a shelf somewhere — rescued from moving-van obscurity, basement darkness, and cardboard imprisonment. Welcome back, my new-found forever friends.

Mark Kingwell is the author of, most recently, Singular Creatures: Robots, Rights, and the Politics of Posthumanism.