I was not yet two when my mother took me to Newfoundland. This must have been 1953 or ’54. I’d check the date, but there’s nobody I can ask anymore. I was the first of four children, the first grandchild on my mother’s side. I was born in Hamilton, Ontario, which is where my father lived all his life and my mother, all her married life.

Whatever its charms, Hamilton was not Newfoundland — a fact that my homesick mother often pointed out. I’m surprised she waited as long as she did to take me back.

As a result of that first trip — and of holidays to Newfoundland that followed for the next fifteen years — I cannot remember a time when I didn’t know who David Blackwood was.

I was ten or eleven when I finally met him — not in Newfoundland but on Georgian Bay. He was not yet then what he would become: one of Canada’s most celebrated artists. He took his education at the Ontario College of Art as seriously as he took his work. There was a scholarship, but he still needed to make some money. As a summer job, he taught art at the camp I attended. He took boys out to Group-of-Seven-looking islands to draw and eventually to paint the rocks and pine trees, the water and clouds (first watercolours, then oils).

With an instinct for dramatic composition.

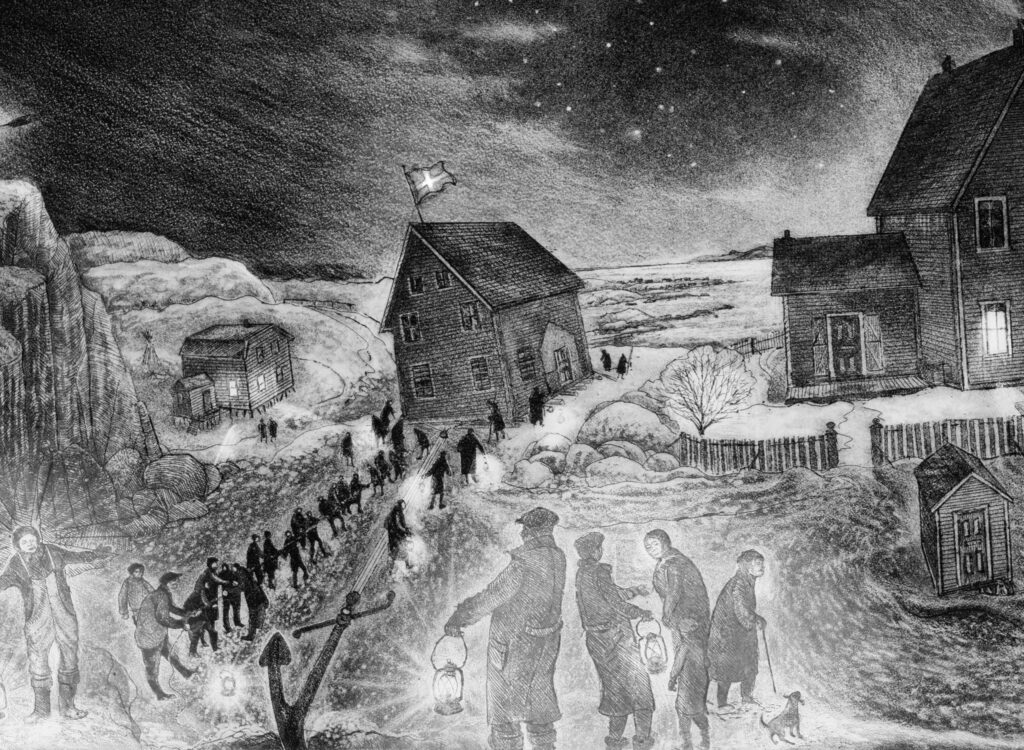

David Blackwood, Bragg’s Island: Hauling Oram’s House, 2018; Courtesy of Heffel.com

The primary means of water transportation at Camp Hurontario was canoe, but art excursions with David were always undertaken by rowboat. And David Blackwood was a good hand with a set of oars. I knew why: I happened to know where he was from.

“Young Blackwood,” as he was called by my Newfoundland relatives, was from Wesleyville, not far along the Straight Shore from the tiny communities of Carmanville and Ladle Cove. These were the outports that my grandmother and grandfather were from. We (the ones from away) divided our summer holidays between Grand Falls, the paper town in central Newfoundland in which my grandparents had settled as adults, and the Straight Shore.

The small, plain house in Carmanville, with its hurricane lamps and featherbeds and bare wooden floors, was (another uncheckable fact) where my grandmother had been born. It had a yard of hay that was as tall as I was, a deep, cool well that we were frequently instructed not to fall down, an outdoor privy, and, across the gravel, sheep-populated road, the Atlantic Ocean.

By the ’50s, the construction company that my grandfather and his brothers operated (sometimes profitably, sometimes not) was engaged in the difficult slog of connecting the towns along the Straight Shore. Until then, these communities were linked on land by trails, if that. Only a short distance apart as the crow flies, they were so isolated from each other that their inhabitants (all of whom my grandfather seemed to know) had distinct (to me, incomprehensible) accents. Gramp said that during the First World War, when the Newfoundland Regiment was under canvas in Egypt, he could walk past the tents and identify which tiny fishing villages the soldiers inside came from by the cadence of their voices.

J. Goodyear and Sons was building the roads between the communities of the Straight Shore, and its construction equipment had to be transported from outport to outport by the company boat. This was the Sylvia Joyce. Too small to be a ship and too big to be a launch, it was a workhorse of a cruiser, with a below deck, a galley (stocked with bags of rock-hard Purity biscuits), and a captain. Captain Blackwood, by name. David’s father.

I’m sure Edward Blackwood had several jobs. Fishermen generally do. But commanding the Sylvia Joyce was a position of great prestige. At least, I thought so. Compared with the other wizened characters my grandfather encountered in our comings and goings, David Blackwood’s father was different. Other adults were addressed as Aunt, Uncle, or Skipper. David’s father, whom I remember as a wiry, taciturn fellow who could haul in a cod on a line as if it were a rock bass, was always Captain Blackwood.

It was because of this connection that I first heard about the prodigious artistic talent of Young Blackwood. He could draw like Michelangelo, my grandfather claimed. He could paint like Leonardo. Young Blackwood was a genius. Unlike quite a few of the claims my grandfather made while in the throes of storytelling about the wondrous personages of the Straight Shore, these turned out to be largely true.

David Lloyd Blackwood, who died this past July in Port Hope, Ontario, at the age of eighty, became one of Newfoundland’s — one of Canada’s — most recognized and successful artists. He was a teenager when he earned that scholarship in Toronto. He was represented in the National Gallery by the time he was twenty-three. At the time of his death, his work was in the Uffizi, the Royal Collection at Windsor Castle, and most major public and corporate collections in Canada.

It may be that Newfoundland plays a big role in my sense of national consciousness simply because my mother was so proud of where she was from, but Blackwood paintings, etchings, and aquatints, such as Fire Down on the Labrador and Lone Mummer, are part of my visual encyclopedia of being Canadian. It’s not the same country without him.

It was early in his career that my mother started collecting Blackwoods, although “collecting” might be a stretch. Her buying was predicated on the available space between the curtains, the piano, and the various oddly placed doorways of our low-ceilinged living room — which wasn’t a lot. But it didn’t take very many prints to make a powerful statement in what was otherwise an ordinary middle-class interior. Blackwood’s work commanded attention. That couldn’t be said of much else on our walls at the time.

My mother’s early acquisition of those Blackwoods was partly an act of loyalty to a fellow Newfoundlander. But it was partly her being shrewd. Not that she had any intention of selling them. She simply enjoyed being on the inside track of something. I remember her saying that David was a serious guy. I think I remember this because she didn’t often use “guy” but did so, it seems, to get her point across to her mainlander children by borrowing a colloquialism. That he was, indeed, a serious guy was obvious in even a brief conversation.

I’m not sure how he managed to convey his serious-guy-ness because he was not at all self-important. In my experience, he wasn’t boastful or demonstrative. Being serious about his work was somehow just part of who he was. Even as a boy, I got the very clear signal that he wasn’t fooling around.

Blackwood was a skilled draftsman with an instinct for dramatic composition. Imaginative, technically brilliant. One of the best printmakers in the world, I venture to say. He was also a masterful storyteller who mined the tales and characters he’d known in Wesleyville for the gold he produced in Port Hope throughout his long and distinguished career. The haunting images of icebergs, whales, flaming ships, and mummers (who wore, I noted, the same mittens my grandmother sent for Christmas) and of huddled, frozen sealers steadily filled my parents’ walls. These were mostly from David’s extraordinary Lost Party series — one of the great achievements of Canadian art. (Go ahead. Check away.)

This was the first lesson David Blackwood taught me: art is transformational. Our house was different with “our Blackwoods” in it. Prior to their arrival, our living room featured a few of the generic European landscapes and bowls of fruit that could be purchased in the “art department” at Eaton’s. To say they were overpowered by the Blackwoods would be putting it mildly. Anybody who stepped inside the front door noticed my mother’s acquisitions. Our walls were suddenly alive in a way they had not been before.

From then on, David Blackwood kept showing up in my life. When I was sent to Camp Hurontario, there he was, the art instructor. When I was sent to boarding school, there he was again, the art master at Trinity College School in Port Hope. And that was the second lesson David taught me: that being an artist, even a successful artist, was not easy. I doubt that taking the boss’s daughter’s family out cod jigging on the Sylvia Joyce was what Captain Blackwood, who had sailed schooners to Labrador and been to the ice floes, thought he was put on earth to do. Ditto, David with his patient, kindly instruction to boys at summer camp and boarding school. But, like his father, Young Blackwood did what he had to do. And did it well. He was a good teacher. It’s just that he also happened to be a great artist.

All this does not mean I knew David Blackwood well. I’m not sure that many people did, aside from his wife of fifty-two years, Anita Bonar Blackwood; their son, David (who died in 2005 at the age of thirty-three); and several close friends and associates. He was a very private man — soft-spoken, kind, and with a will of steel (as the Globe and Mail pointed out in his obituary). And it was that will of steel that made him so different from everyone else. He was the first real artist I knew. Lucky me.

David Macfarlane is the award-winning author of The Danger Tree. His next book, On Sports, comes out this year.