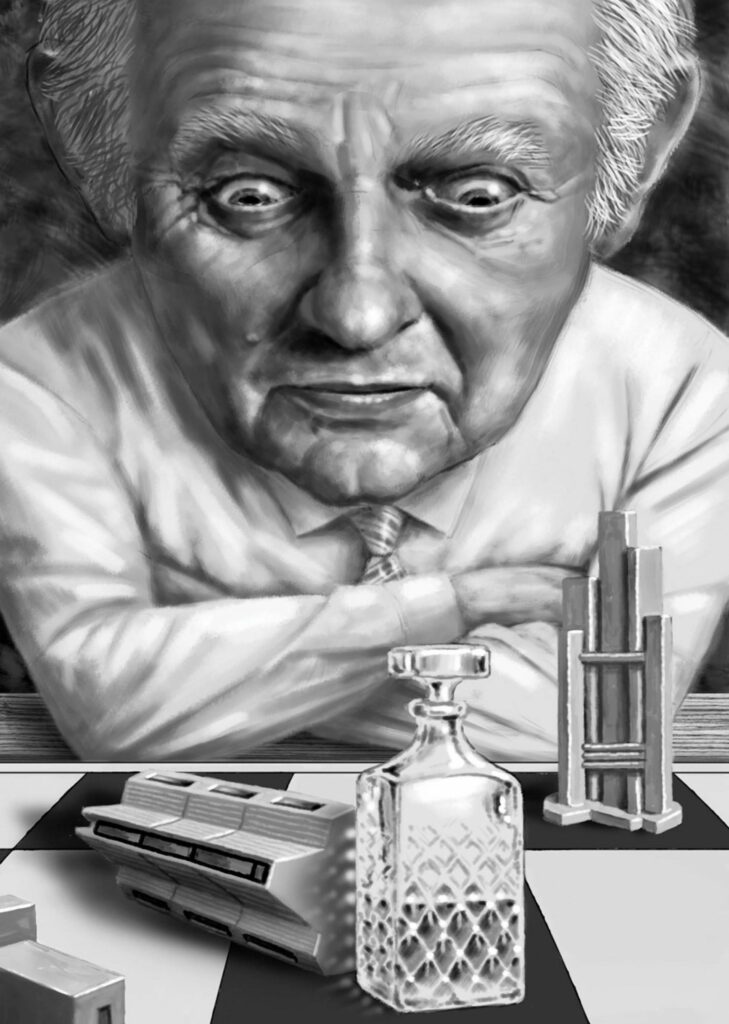

As the creator of iconic landmarks, such as Massey College in Toronto and much of Trent University in Peterborough, Ontario, and many remarkable houses, Ron Thom endures as one of Canada’s most distinctive architectural talents. He was a high-profile participant in the creative world during the 1960s and ’70s, that vibrant and optimistic period of ours. For over twenty years, his houses in Toronto and Vancouver regularly appeared in shelter magazines and were aspirational for the cool kids of his generation — like Murray and Barbara Frum. Thom had a charismatic personality, especially evident when he was talking about design or making a home materialize for a client on napkin sketches over cocktails. Although he became a difficult personality as he aged, his magnetism engendered great loyalty from his friends and clients alike. This sounds like a happy story, but it’s not.

As Adele Weder’s Ron Thom, Architect chronicles, this “creative modernist” had no easy road as he navigated two marriages, multiple affairs, business struggles, and, most disastrously, a seemingly untreatable addiction. Years of heavy drinking likely hastened his death in 1986, at sixty-three. Some wondered how he had survived as long as he did. In fact, I was one of them, especially after my sole encounter with the man. He’d given a talk and then invited a group, including several architecture students, to have drinks. This turned into an unsettling experience: watching a legendary practitioner as he was hustled into a cab, so drunk he couldn’t speak.

It was only a few years later, after being kicked out of his own firm the month before, that Thom died. His funeral was attended by hundreds, including “politicians, tradespeople, planners, clients, academics, critics, and friends.” Despite his alcoholism, his dedication to design and to the craft of making buildings never wavered. Many people admired him for these traits even when he was no longer an architect they’d likely hire. The crowd at Toronto’s St. James Cathedral celebrated a tortured artist — one who had managed to leave a significant legacy, both in his buildings and in his impact on the next generation of designers.

Thom’s approach to architecture was inclusive. He embraced landscape, furniture, lighting, even ashtrays as vital components of the built environment. He especially loved wood. His ability to site buildings, modulate their natural light, and add crafted details that enriched their day-to-day use remains unequalled. Thom was a true talent, and Weder captures how hard it was for him to create in a world that saw buildings not always as marvellous places to enhance life but rather as the more prosaic outcome of functional or commercial imperatives.

Weder tells a fascinating story of an artist’s journey that began when Thom was a shy boy and wannabe concert pianist — or at least that’s what his mother wanted him to be. She pushed him to perform, with mixed results, and though he was very good, he was not great. “Despite his certificates and trophies,” Weder writes, “it seemed that Ronny’s musical prowess could not reach the ultra-high level required to make a profession of it.” She speculates that “he could not reliably heed the old-world penchant for a gentle, even, predicable tempo.” She also wonders whether “this signalled his innate creativity, wanting to inflect the composition with his own tempo rather than slavishly follow a score.” Regardless of what the young man lacked musically, he could draw. So he decided to switch his focus.

Thom began studying at the Vancouver School of Art, part-time, in grade 12. He went full-time after he graduated from high school in 1941. He wasn’t there long before he joined the Royal Canadian Air Force in 1942; he married Christine Millard on a special leave in 1944 and was honourably discharged in March 1945. “Ron came back to Vancouver with a veteran’s allowance to bankroll the rest of his art education,” Weder writes. He was no longer the skinny guy he once was, and he wasn’t a sober one either. As Chris Millard later recalled, her husband “came back soused.”

His life versus his legacy.

John Fraser

Thom had been a standout in art school. One of his teachers, the well-known painter Jack Shadbolt, described him as being part of “one of the most significant creative groups in Canada today.” This was in the pages of Canadian Art ; Thom’s painting At the Fair Grounds accompanied the November 1946 article. “Its centrifugal composition would eventually become Ron’s signature approach in architecture as well as art,” Weder says of the image. Thom’s work — this time a portrait — reappeared in Canadian Art the following year, in a story that also featured a landscape by Emily Carr. But getting noticed was one thing. Being able to make a living as an artist was another — and Thom wasn’t sure how he could do that and someday raise a family.

In 1949, an established Vancouver architectural firm, Sharp & Thompson, Berwick, Pratt, wanted an illustration of a house on a waterfront site and asked a local draftsman, Doug Shadbolt, if he could do it. He knew he couldn’t, so he contacted his brother for a recommendation. Jack Shadbolt suggested a former student, Ron Thom.

Weder describes how Thom’s illustration “astounded everyone in the room,” even though it was not right for that particular project. He had clearly demonstrated his talent, and on June 1, 1949, he began an apprenticeship at the firm and his transition from artist to architect. “Ron quickly showed himself to be far more than an illustrator,” Weder writes, and the managing partner, Ned Pratt, “soon assigned Ron as the design lead or co-designer on projects that needed an artist’s eye.” Within a few years, “Ron could easily design up to ten houses at a time” when collaborating with other draftsmen.

In February 1960, a year before his divorce from Chris, Ron “received a letter that would change his life forever.” It was a request to submit a preliminary design for Massey College, a new interdisciplinary postgraduate community on the University of Toronto campus, to be funded by the Massey family. He would be up against Arthur Erickson and John Parkin, working with Carmen Corneil. Thom’s scheme — an interior-focused building, the perfect cloister for scholars — eventually won. Weder suggests that his “real-life introversion” may have helped him understand the brief “at a more personal level than his extroverted competitors.”

Massey College officially opened in 1963 (the same year its architect married his second wife, Molly Golby). With the commission, Thom realized, for the first time at a large scale, his vision of creating a unified environment, while also employing some of the “classic Frank Lloyd Wright principles” that he had incorporated in his earlier work. It launched his life — and career — in Toronto.

The college remains one of the most wondrous buildings in Canada. (It is also where this magazine is edited each month.) As Weder notes, the structure illustrates an alternative to the “stark, unadorned boxes or fusty pseudo-historical mimicry” of the time. She describes it as “contemporary and yet crafted, like a jewel box of brick, wood, leather, ceramic, and wrought iron. A geode, with an inscrutable brick exterior sheltering the magic within.” I still remember when I first saw it while studying architecture across campus. My school was a Le Corbusier modernist kind of cult, and I was uncertain whether I ought to like this Oxbridge-inflected place, with its intricate detailing and crafted — rather than industrial — furniture and lighting. I quickly realized that my love of Massey College would be a forbidden one.

A major commission for Trent University followed for Thom, even before Massey College was completed. And in the 1970s, he drew up plans for the Shaw Festival Theatre in Niagara-on-the-Lake, Ontario, Pearson College of the Pacific in Victoria, and St. Jude’s Cathedral in Iqaluit. He also created numerous houses. But it was an increasingly tumultuous time for Thom — in both business and life.

Ron Thom, Architect methodically reviews the man’s oeuvre (although more photographs and plans would have given a better sense of his work). Weder includes various perspectives from his collaborators and clients, and she does a nice job of discussing his influences. But her strength is as a meticulous architectural historian, not a biographer. There was a lot going on in her subject’s life, much of it dark, about which Weder chooses not to be explicit. This doesn’t impact the architectural history, but it does mean Thom’s life is framed perhaps too politely.

“Family members have previewed the most sensitive and detailed passages that pertain to their own individual memories,” Weder writes in her introduction, and this approach may have resulted in the rather sanitized story. Such restraint masks a true understanding of Thom, one that goes beyond an aesthetic appreciation. While it’s touching that former colleagues and family members might want to protect Thom, other facets of his personality would have made for powerful — and welcome — biographical elements.

In eulogizing Thom in 1986, the broadcaster Barbara Frum eloquently expressed the architect’s vision and the experience of working with him on her often photographed house: “Ron was an artist who made a refined aesthetic out of unrefinement, a master of the difference between complexity and fussiness. He taught us how to love raw surfaces and the natural, to recognize harmonious proportions.” Most who experience Thom’s work today never knew him. Indeed, some do not even recognize his name anymore. Now his buildings must speak for themselves. I hope it’s solace for Ron Thom that so many still want to hear what they have to say.

Kelvin Browne, recently left the contemporary art world to sail in Chester, Nova Scotia.