I thought I had grasped the profound pain caused by the current opioid crisis, but that was before I read Tara McGuire’s Holden After & Before. With unflinching honesty, McGuire tells the story of her twenty-one-year-old child, who died in 2015 of an accidental opioid overdose. Although the memoir is subtitled a “love letter” for a lost son, this book is not for the faint of heart.

Mother and son may have been bound by love, but they were torn apart by trauma. McGuire describes Holden’s emotional turmoil and his devastating descent into drug addiction, which “seems to be the only disease where you have to wait until someone falls through the ice and nearly drowns before you can throw them a rope.” She is just as open about her own failings as a mother, along with feelings of shame, guilt, and sorrow. Her late realization that Holden — who likely had borderline personality disorder — might have survived had his mental health challenges been recognized and treated is a burden she will carry for life.

She loved him unconditionally.

Jamie Bennett

In many respects, Holden was a typical adolescent. As McGuire recalls, he regularly chose the company of friends over family, and when at home, he retreated to his basement bedroom. He frequently attended parties, which always featured loud music, beer, and weed. Sometimes they were violent. He was also a graffiti artist. Drawn to Vancouver’s urban surfaces, he tagged mailboxes, newspaper stands, and construction sites. “The more he etches his mark on the city,” McGuire writes of a distant afternoon, “the more settled he feels in his skin.” For Holden, the promise of release offered by those cans of spray paint was both tantalizing and necessary.

The thorny relationships between Holden and his family members will be familiar to many parents of teenagers. Holden’s dual wish for independence and connection paralleled McGuire’s simultaneous desire to prepare her son for adulthood and shield him from hardship. Holden’s juvenile hostility and insolence eventually alienated his stepfather, Cam. And though Holden and his young sister, Lyla, got along, they were separated by a ten-year age gap and different dads.

While Holden’s story propels the narrative, McGuire’s layered text also details her efforts to come to terms with her son’s death. To do so, she undertakes her own study of the “epidemic of despair” that is the opioid crisis. She conducts research into addiction, visits Vancouver’s Overdose Prevention Society to learn about and witness supervised heroin use, and discusses Holden’s psychological profile with his family doctor. She meets with his former friends, lovers, roommates, and co-workers, who all help her reconstruct his final year of life and better understand who he was.

McGuire also reflects on her role in Holden’s decline and the remorse she feels for not being present during those final months. She spent that year, which capped a decades-long career in radio broadcasting, travelling the world with Cam and Lyla, while her son remained in Vancouver and worked at various jobs. “I will forever question our decision to leave, to abandon Holden for so long,” she admits. “If I’d stayed home and paid attention, would he still be alive?”

McGuire responds to this self-imposed question by taking up her pen and writing with courage and insight about Holden and her feelings as a bereaved mother. Desperate “to make sense of Holden’s gaping absence,” she assembles a range of “flimsy building materials” to construct her “imagined story”: notes, emails from doctors, redacted police files, a coroner’s report, photographs and screenshots, social media posts, personal text messages, graffiti tags, and childhood drawings, as well as her private memories and interpretations.

McGuire reviews the stages of Holden’s life, from infancy to late adolescence, and tries to pinpoint the source of his anxiety and depression. With hindsight, she sees that he was left wounded, at age three, when she and his father divorced. Holden was shuttled between two homes and could not find comfort and calm with either parent. McGuire speculates that detachment became his “survival instinct” and that adolescent restlessness was a symptom of his insecurity.

She tries not to blame herself for her son’s difficulties. At the same time, she acknowledges that she bears some responsibility for his death. Although she sensed his emotional strain, she now appreciates “that he couldn’t tell me he was in trouble with his mental health.” McGuire concedes that she “didn’t fully see or understand him and what his struggles were really about.” Her biggest regret, however, is “that when he needed me most, I was on the other side of the planet.” To read this admission is to feel her agony.

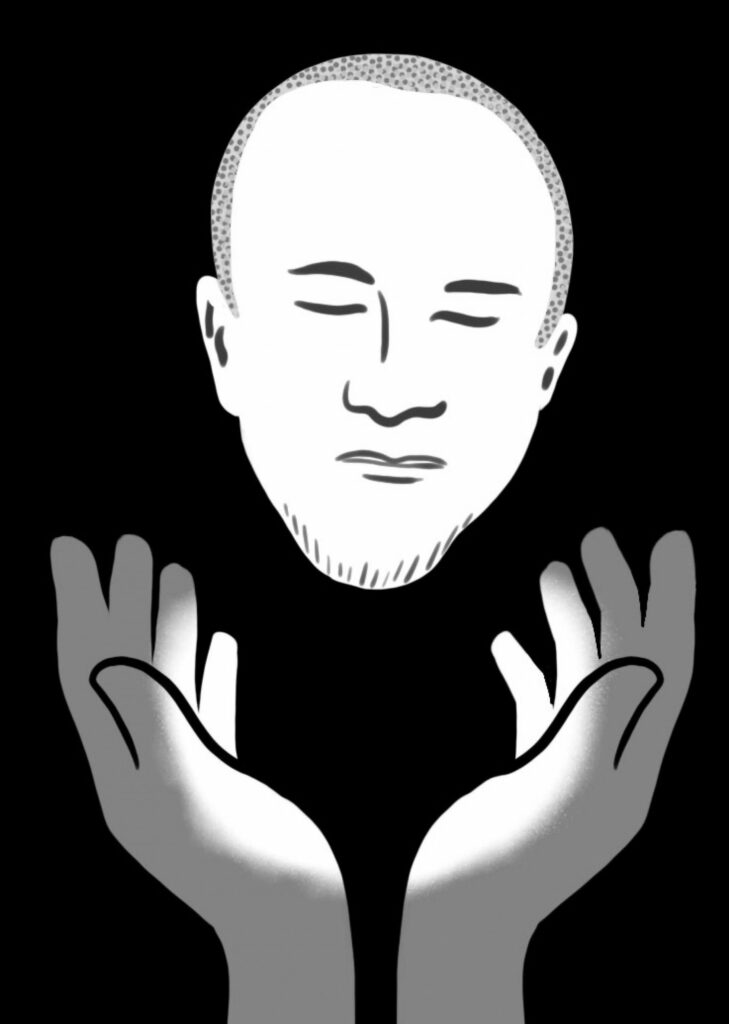

Mothers of children who die of drug overdose often bear a burden of shame and guilt. But what this memoir shows is that mothers can also be their children’s greatest allies and supporters. McGuire coached, counselled, and consoled her son. She offered him help, even when he rejected her care. She loved him unconditionally, and he returned that love. Holden missed his mother “like crazy” when she was travelling. McGuire may not have been present in his last year, but she was an abiding and adoring presence throughout his life.

Surprisingly, we learn very little about Holden’s other parent: his “deep-voiced” father, who remains a shadowy figure in the background of these pages. Surely he must share the weight of responsibility and suffering that McGuire claims for herself? During the ten-month period when Holden slid deeper into drug use, his father was living in Vancouver. Did he not see what was happening to his son? Could he not have intervened somehow?

McGuire does not address these questions, but they will linger in the reader’s mind. In the end, though, this is her story — one that she shares with the poet Lynn Tait, whose son, Stephen, died in 2012 of a fentanyl overdose. In her poem “The Enemies We Cannot See,” Tait articulates a mother’s anguish, guilt, and enduring love: “I want to lift him up, / but my hands are tied, my back broken. / His death cuts into me.” For McGuire, as it is for Tait, to write of her son is to confront his death by overdose and then to lift him up and onto the page.

Ruth Panofsky teaches English literature at Toronto Metropolitan University.