On April 3, 2020, just over three weeks after the World Health Organization declared COVID-19 a pandemic, Nova Scotia’s premier, Stephen McNeil, uttered four unforgettable words: “Stay the blazes home!” That public plea, spoken in the company of the chief medical officer, Robert Strang, did more than attract national attention. It also turned the Liberal politician into a Maritime folk hero, quickly celebrated with homegrown memes, songs, lawn signs, beer cans, and T-shirts.

Threatened and unsettled by the virus, Nova Scotians responded enthusiastically to McNeil’s father-figure style of leadership. As illustrated in Len Wagg’s best-selling picture book Stay the Blazes Home, the populace took his words to heart, by sheltering in place, adhering to public health restrictions, and leaving downtown streets, provincial highways, and normally crowded public spaces eerily silent and essentially abandoned.

In many ways, Stephen McNeil of Upper Granville was an unlikely folk hero, just as he had been an unusual choice for Liberal leader in April 2007. Gangly, a bit awkward, and laboured in his public speaking, the former appliance repairman edged out Diana Whalen, a Halifax MLA, for the position to become leader of the opposition. Almost everyone, particularly in the provincial capital, underestimated his capabilities and steadiness of purpose. But McNeil, who stands six foot five, proved to be a towering figure in more ways than one.

In office, as the veteran journalist Dan Leger makes crystal clear in this much-anticipated biography, McNeil exuded Annapolis Valley authenticity and never abandoned his homespun political integrity. Stephen McNeil: Principle & Politics, which covers his rise to power and tumultuous time at the helm of the government, from 2013 to 2021, is bound to cement his reputation as one of the “most consequential Atlantic premiers of recent years” (to use the Halifax pollster Don Mills’s phrasing).

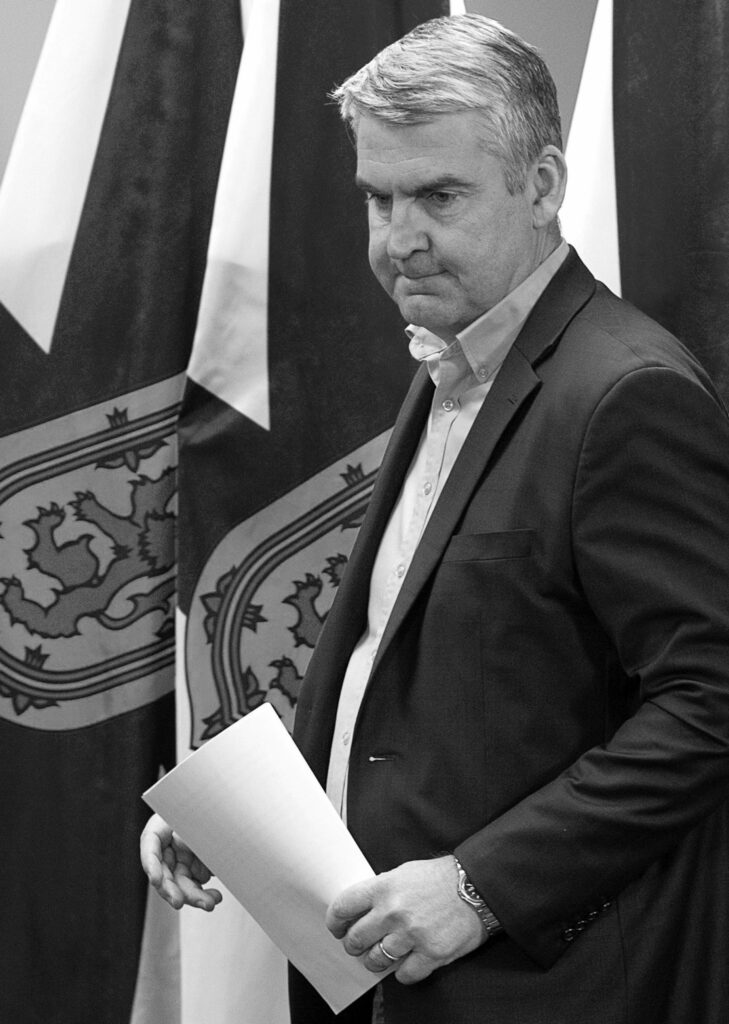

At a COVID-19 briefing on March 15, 2020.

Andrew Vaughan; The Canadian Press

Instead of falling into the trap of simplistic labelling —“courageous leader” or “schoolyard bully,” for instance — Leger paints a reasonably fair, textured, and balanced portrait of Nova Scotia’s twenty-eighth premier. While McNeil was a big-L Liberal, Leger shows how he also embraced many small-c conservative values: self-reliance, thrift, forthrightness, and a caring concern for the neglected and disadvantaged. Viewed through this lens, his seemingly contradictory policy decisions make more sense.

McNeil stood resolute, inspiring intense loyalty and staring down determined resistance. He prided himself on being a modest man from a normal, hard-working family. (An earlier glowing biography, Premier Stephen McNeil: A Story of a Nova Scotian Family, by his Annapolis Valley friends Dave and Paulette Whitman, helped burnish that image.) But as Leger points out, there was nothing “normal” about being raised as one of seventeen children, even in a Catholic family, nor about witnessing your father choking to death at the kitchen table, nor about watching your mother appear on the CBC’s Front Page Challenge. (Theresa McNeil, who had been appointed the country’s first female high sheriff, stumped the show’s panellists.) In fact, much of McNeil’s intestinal fortitude came from his mother’s side. “You knew who the boss was,” he told Leger. “We idolized her. She was the rock we stood on.”

According to Leger, McNeil “proved himself a premier of consequence” through his leadership style and decisive actions. In 2013, he toppled the NDP government of Darrell Dexter with a well-timed, effective campaign that targeted Nova Scotia Power and its escalating electricity rates. Once in office, he “took pains” to make the province more welcoming to outsiders. By accepting Syrian refugees and increasing immigration, as well as by doubling trade with China, it was able to reverse population declines. McNeil also took a few political risks that were guided by principle. Shutting down the polluting paper mill at Boat Harbour, making amends with former residents of the Nova Scotia Home for Colored Children, and stepping up during the pandemic are all prime examples.

McNeil’s most formidable challenge, inherited from the Dexter government, was putting the province’s financial house in order. Uncontrolled spending, a mounting deficit, and ballooning costs dictated his priorities. Working with a small team of advisers, loosely coordinated by the Liberal insider Bernie Miller, McNeil cobbled together a four-point strategy: consolidate health care bargaining units, designate health care workers as essential, impose a wage constraint framework on the public sector, and exploit divisions in labour ranks by pitting public-sector unionists against private-sector workers. Toughing it out, according to the former NDP finance minister Graham Steele, was McNeil’s “single biggest accomplishment.”

Balancing the budget and imposing wage restraints earned McNeil the enmity of many, particularly the Nova Scotia Teachers Union. Much like Mike Harris in Ontario in the 1990s, McNeil faced mass protests — and was vilified by educators. He did succeed in reining in the deficit and managed to win, albeit narrowly, a second majority government in 2017. But relentless opposition eventually wore the premier down, sparking periodic flashes of anger and reportedly hastening his departure from office. (The recent Nova Scotia Supreme Court decision on the unconstitutionality of the “vengeful” law imposing the NSTU contract came too late to be factored into Leger’s account.)

Leger makes a fairly persuasive appraisal of where McNeil ranks among Nova Scotia’s first ministers. While the Liberal premier Angus L. Macdonald (1933–40 and 1945–54) sets the benchmark, McNeil is near the top, comparable to two Progressive Conservatives, Robert L. Stanfield (1956–67) and John Buchanan (1978–90). What’s a bit surprising is that Leger doesn’t draw comparisons with New Brunswick’s Liberal titan, Frank McKenna (1987–97), who resigned, like McNeil, while still in public favour. More might also have been said about McNeil’s personal affinities with another rural Bluenoser, the Progressive Conservative premier John Hamm (1999–2006).

In tackling McNeil’s contentious and contested political career, Leger walks a fine line and delivers a remarkably judicious post-mortem. This book will surely stand as the definitive biography of the “Stay the blazes home!” premier.

Paul W. Bennett is an author, education columnist, and regular guest commentator on talk radio. He lives in Halifax.