In Canadian Spy Story, David A. Wilson thoroughly and insightfully examines Canada’s struggle against the Fenians, nineteenth-century radicals also known as the Irish Republican Brotherhood. They recruited fellow Catholics who had fled to the United States and Canada to escape British misrule over Ireland. Cultivating a powerful sense of grievance, they called attention to the nearly one million killed by the Great Famine of the late 1840s, which they blamed on greedy landlords and a callous imperial government.

While some American Fenians targeted Ireland for subversion, most thought their native land too far away and too well guarded by the Royal Navy for invading with any prospect of success. Canada, a closer and more vulnerable target, offered a better opportunity for smiting the hated empire. Radicals hoped that their invasion would provoke a massive war between Britain and the United States to tie down redcoats and the Royal Navy, improving the prospects of revolution in Ireland. The Fenians’ ideology fed on republican animus against the Canadian ties to the Crown. Their moment came in the summer of 1865, after the Union crushed the Confederate rebellion in the southern states. To save money, Washington rapidly demobilized 800,000 troops, trained in the latest military methods and weapons. About 100,000 of them were Irish and potential recruits for the Fenian activists.

The venture also appealed to American expansionists, including many who resented the wartime reception that Canada had offered to Confederate agents and escaped prisoners. But the American Fenians put their Canadian brethren on the spot. Would they defend their new homeland or welcome Fenian invaders from south of their border?

Fenians were a minority of an ethnic minority. Most Irish immigrants to North America were too busy with families, work, and church to engage in radical politics, but many felt some kinship with the noisy activists. Those radicals tended to live in towns, rather than on farms, and to work as artisans or shopkeepers: neither rich nor poor but middling. More radical than pious, Fenians gathered in taverns and meeting halls rather than in church. Clerics usually denounced violent radicals as reckless and immoral troublemakers.

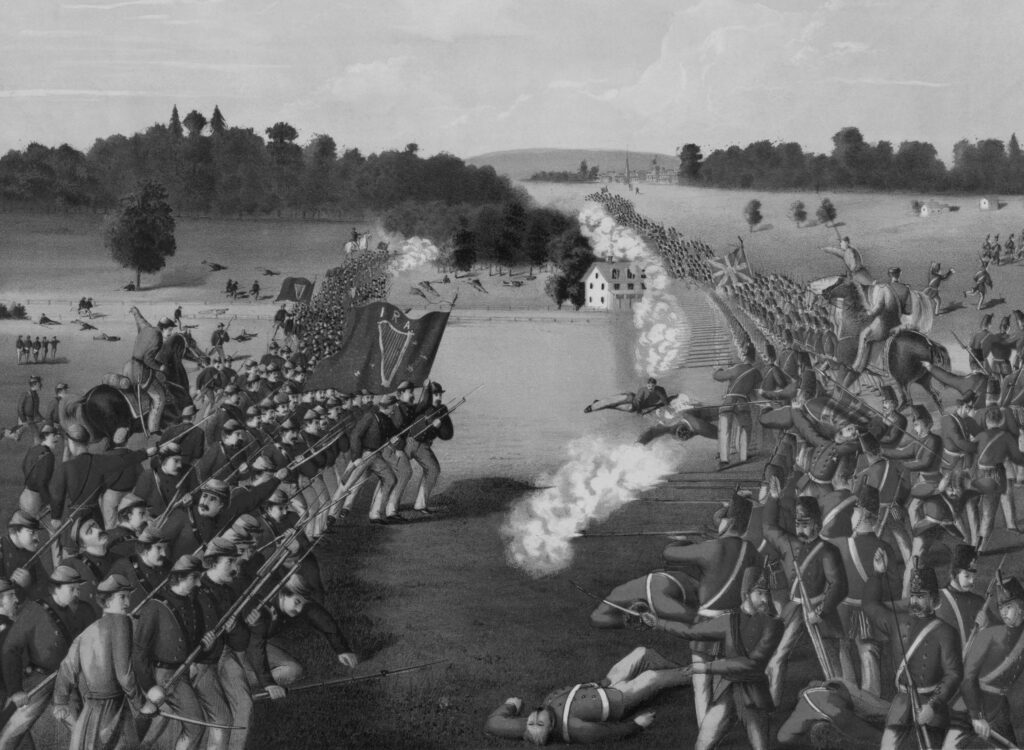

Fenian invaders engage with the Queen’s Own Rifles at the Battle of Ridgeway in June 1866.

Sage, Sons & Co., 1869; Library of Congress

Although nearly a fifth of Canadians were Catholics of Irish descent, most cherished British Canada for offering them improved economic prospects and the political rights denied to them in Ireland. Fenians in Canada preferred to make trouble in Ireland rather than invite it into their backyard. Irish Catholics would brawl with Orangemen in the streets of Toronto, but few wanted to help Americans conquer and republicanize the place. Because true Fenians were relatively rare in Canada, and mostly averse to invaders, the American Fenians would have to win largely on their own.

Canada’s leading Irish politician, Thomas D’Arcy McGee, denounced the Fenians as a menace to Canada in general and to the Irish community in particular. Once a radical agitator when young in Ireland, McGee had emigrated to the United States, where he soured on republicanism as corrupt, demagogic, and tainted by slavery. Moving north in 1857, McGee embraced Britain as the world’s freest empire and Canada as the ideal land of opportunity. A newspaper editor turned politician, he had a quick wit, a rich singing voice, and a capacity for alcohol that impressed even John A. Macdonald. Most Irish Canadians supported McGee, but some Fenians promised a thousand dollars for killing the traitor.

As the attorney general of Canada West, Macdonald was not one to take chances. Of the Fenians, he declared in September 1865, “I am watching them very closely . . . and think that the movement must not be despised, either in America or Ireland. . . . I shall spare no expense in watching them on both sides of the line.” Led by Frederick William Ermatinger in Canada East (now Quebec) and Gilbert McMicken in Canada West (now Ontario), Macdonald’s secret agents infiltrated groups in Montreal and Toronto. But Macdonald and his spymasters especially targeted the more troublesome Fenians in Chicago, Detroit, Buffalo, and New York City.

Fenian leaders hoped to strike on St. Patrick’s Day 1866, when winter’s ice would still block the British from rushing reinforcements up the St. Lawrence River to Montreal and points west. But the Fenians struggled to organize, move, and arm enough recruits along the border. In April, they did assemble about 500 armed men in Eastport, Maine, to attack the nearby island of Campobello. Tipped off by informers, the British sent warships, and New Brunswick mustered militiamen to block the raid. After burning a Canadian customs office on a smaller island, the Fenians dispersed homeward. This debacle led Canadian authorities to let down their guard, assuming that the worst had passed.

On June 1, about 800 armed Fenians surprised Canadians by crossing the Niagara River to land near Fort Erie. They wore a mix of uniforms, some Confederate grey, more in Union blue, and others in their own green. Advancing into the interior, they defeated hastily assembled and ill-trained militiamen near the village of Ridgeway and won another firefight near Fort Erie. Fenian leaders had expected that news of a victory or two in Canada would so enthuse Irish Americans that thousands would flock to join the invasion. Hearing crickets instead, the Fenians withdrew back across the river to New York on June 3. A belated presidential proclamation denounced the cross-border attacks, which irritated Irish Americans but did nothing for Canada’s dead fighters.

Elsewhere in June, other attacks fizzled. The Fenians in Chicago and Detroit never mustered enough men to cross over at Windsor. A thousand Fenians did assemble in northern Vermont to strike into Quebec’s Eastern Townships, but they were far fewer than the 8,000 expected. And their invasion lasted only two days and accomplished nothing beyond looting a few farms and stealing one British flag.

Wilson, a professor at the University of Toronto and the general editor of the Dictionary of Canadian Biography, astutely notes that the Fenians suffered from a classic cycle of nineteenth-century radicals. To attract followers willing to fight or pay, leaders had to talk big: of growing thousands of supporters and immense stockpiles of weapons; of subverted Irish troops willing to betray British garrisons; and of thousands of Irish Canadians longing for liberation. But as the winter of 1865–66 passed without an attack, critics within began to fault the leaders as frauds collecting money without delivering invasion. To maintain credibility, the Fenian leaders had to strike in June, but by faltering they lost face. No garrisons mutinied; almost no Canadians showed support; and most Irish Americans just stayed home. Disappointment then bred feuds as leaders traded blame.

Canadian historians have struggled to make sense of the Fenian incursions. During the twentieth century, nationalist historians disparaged them as buffoons. J. M. S. Careless, for example, dismissed Fenians as dupes led by “braggarts and muddleheads.” Donald Creighton called them “a crew of grandiloquent clowns and vainglorious incompetents.” Drawing on overworked caricatures of the Irish as garrulous, bombastic drunks, such scholars insisted that the Fenians inevitably botched their “comic opera” invasions. Yet these same historians argued that the intrusions suddenly pushed fractious Canadians to create a confederation as their best security against the hive of trouble known as the United States. The contradictions in the standard version of Fenianism invite the question: How could a set of supposed clowns have so much clout?

Wilson takes the Fenians seriously: as numerous, sincere, and effective at keeping secrets and promoting their cause. Although almost all Canadian Fenians stayed clear of any American invasion, Wilson insists on their relevance to the story. He recognizes the writer’s pitfall of special pleading for his or her topic as being so much more important than it appears to others. But he also struggles to avoid that pit himself, particularly in assessing the Canadian numbers.

Wilson begins wisely: “It is impossible to ascertain exactly how much support there was for Fenianism in Canada during the 1860s.” After all, radicals exaggerated their numbers to attract converts, and security officials follow suit to justify more men and money to watch the threat. To avoid arrest, the truest Fenians worked hardest to keep their secrets. Surviving membership lists are few, partial, and generally suspect. Much also depends on defining a Fenian: Anyone who favoured violence against Britain in theory? Or someone who actually funded and fought to wreak havoc on the empire? Lots of Irish folk hated the British, but relatively few were ready to kill them in North America.

Fenians claimed 2,500 members in Montreal, but Wilson endorses a contemporary estimate of only 355 (out of 5,700 Irish in the city, or 6 percent). Despite that paucity, he concludes, “Fenianism was a serious force in Montreal.” After wading through conflicting and murky evidence, Wilson reaches a surprising precision for all of Canada: “A reasonable supposition is that around 10 per cent of Irish-born adult Catholic males strongly supported the Brotherhood, whether or not they were actually in a position to join it.” We are better off heeding the sage conclusion of the British consul in New York City, Edward Archibald, who investigated the Fenians more thoroughly than any other official: “Most of the Fenians seemed quaintly reluctant to kill, do not believe it is possible to extract the truth from any of the parties inside or outside of Fenian Circles. . . . All opinions formed of the strength of the Fenians or their intentions and plans are necessarily vague and unsatisfactory.”

Most of the Fenians seemed quaintly reluctant to kill, and seldom did they fight a battle in a field rather than in a meeting hall or newspaper. Fenians loudly threatened every informer with a quick bullet to the head. Yet when they did suspect an informer, he got every opportunity to talk his way out of trouble — however implausibly — or the Fenians just warned him to get out of town and waited with surprising patience. Despite pretty flimsy covers and impressive drinking problems, none of the Canadian detectives died at Fenian hands.

In this story so rich in rhetorical violence, the Fenians killed only a handful of militiamen in one fight and staged a single assassination. Granted, the target was a big name: Thomas D’Arcy McGee, gunned down while returning from Parliament to his lodgings in Ottawa in April 1868. But his death attests more to the limits than to the prowess of Fenianism. The convicted murderer, Patrick James Whelan, was an obscure tailor without much of a track record as a Fenian. He acted with one other accomplice (possibly the real triggerman) and without any authorization from Fenian leaders. For weeks, he had stalked McGee, including during debates inside Parliament, but repeatedly lacked the nerve to shoot. Whelan went to the gallows protesting his innocence, although his gun was surely the murder weapon. Wilson plausibly speculates that the accomplice got fed up with Whelan’s dithering, grabbed the pistol, and pulled the trigger, leaving Whelan to take the fall.

Wilson concentrates his story on the detectives assigned to infiltrate the Fenians’ gatherings, particularly in the United States. The star of the show is Charles Clarke, a character suited to a potboiler. Born into a Catholic, Gaelic-speaking family in Ireland, he had converted to Protestantism and joined the militantly anti-Catholic Orange Order. Migrating to Canada, he entered the Toronto police. Although not usually known for personal morality, the force dismissed Clarke as too lewd for it. Despite having a wife and child, he brazenly consorted with women of low reputations. But he was snapped up by Macdonald’s agent Gilbert McMicken to join his detectives because it was so hard to find Gaelic speakers willing to spy on their countrymen. Adapted to the tavern world of hard drinking, festive singing, eloquent lying, and prostitution, Clarke was, for a time, the ideal operative. Talented at conning others, he posed as a Missouri cattle dealer willing to invest in Fenian operations. Clarke became a fast friend of the leading American Fenian, William Roberts, after giving his boy a pony.

But Clarke was headed for a fall, as he alienated his latest loose woman, who had the implausibly perfect name of Miss Clapp. She exposed his identity to Fenian leaders, so Clarke fled back to Canada. McMicken then sent him to Britain to help protect Queen Victoria from a supposed assassination. In fact, the plot was a scam hatched by Fenians to harry and mock British security. Botching that assignment, Clarke again had to come home. This time, he got the boot from the top — fired by Macdonald, now prime minister — and vanished from the historical record after 1868.

“It is easy to be seduced by the story,” Wilson declares. Would that he had emulated Clarke and been more seduced. Indeed, this volume reads best when focused on a few key characters, including McGee, Whelan, Clarke, McMicken, Macdonald, Roberts, and Miss Clapp. At times, Wilson lets loose in a breezy, narrative style: “It was Charles Clarke’s penis that did it” opens one chapter. More often, however, he includes every note taken for a complex, complicated project involving many liars. And Wilson is a most dogged researcher with an indulgent editor. The book seems to discuss every person ever remotely associated with Irish radicalism in two countries — along with multiple shifting perspectives on his credentials as a Fenian. A hundred pages sliced from the text would have rewarded readers with a clearer, more consistent narrative that made the most of the colourful cast and dramatic story embedded in Canadian Spy Story.

Alan Taylor recently published American Civil Wars: A Continental History, 1850–1873.