Last August, the residents of Montreal’s well-heeled Outremont neighbourhood were treated to a curious scene. Librairie du Square was hosting a reception to welcome the poet and novelist Emmelie Prophète, who had been appointed Haiti’s minister of culture a few months before. On the sidewalk outside the bookstore, a sole protester rolled out a banner that declared Prophète a kolabo — or collaborator, in Haitian Creole. In that same language, he loudly denounced the author as part of the political elite that had caused his exile. The celebrated writer Dany Laferrière, the most recognizable Black man in Quebec letters, sat on a park bench next to him and argued back in French.

The moment highlighted Montreal’s status as a centre for Haitian publishing and politics, a space where waves of exiles and immigrants meet and sometimes clash. During the 1960s, it became a hub for those fleeing the dictatorship of François Duvalier. Largely French-speaking and highly educated, these Haitians founded their own presses and cultural centres — and were key contributors to the Quiet Revolution. In the decades that followed, a far wider array arrived, including many who spoke only Creole and came from poorer backgrounds. These days, people travel back and forth in a steady stream between the Caribbean nation and Canada’s second-largest city. As do books.

Despite the many government grants designed to facilitate exchange between Canada’s two official languages, Haitian writers who publish in Quebec are not often translated into English. Even Laferrière, the first Canadian and the first Black man elected to France’s prestigious Académie française, has seen only a portion of his work made available to anglophones. It is thus refreshing to see novels by Prophète and Marie-Célie Agnant recently appear in English, in editions that follow industry best practice by listing the translators on their covers. Prophète, a bestseller in Quebec, lives in Port-au-Prince but has published with Montreal’s Mémoire d’encrier for nearly twenty years. And Agnant, who moved to the city as a teenager in 1970, is among the most recognized Haitian Québécois writers, with an oeuvre that includes poetry, fiction, and young adult literature.

Agnant’s A Knife in the Sky follows in a robust tradition of protest literature against the Duvalier dictatorship. (François “Papa Doc” Duvalier ruled Haiti from 1957 to 1971, and his son then ran the country until 1986.) First released in 2015 as Femmes au temps des carnassiers, by the feminist press Éditions du remue-ménage, it examines the early years of the regime through the experiences of women. The first section follows the journalist Mika, who publicizes the government’s crimes despite escalating threats to her safety. She is punished for defying the state and for daring to participate in the public sphere; once she is taken into custody, Duvalier himself proclaims, “That’ll teach her to trade in brooms and needles for a quill.” The narrative as a whole is haunted by the use of rape to terrorize political dissidents and their family members.

Toronto’s Inanna Publishers describes A Knife in the Sky as “preoccupied with colonial imposition.” Although Duvalier’s anti-Communism secured him the support of the United States, the novel actually focuses less on Western imperialism than on attacking the regime as a form of fascism. This is particularly the case in the second section, which follows Mika’s Spanish-born granddaughter Junon. When Junon travels to Haiti and encounters a man who tortured her mother, Soledad, he insists, “I was an army officer, I was just obeying orders.” The parallels between the Haitian dictator and Francisco Franco are easy to see.

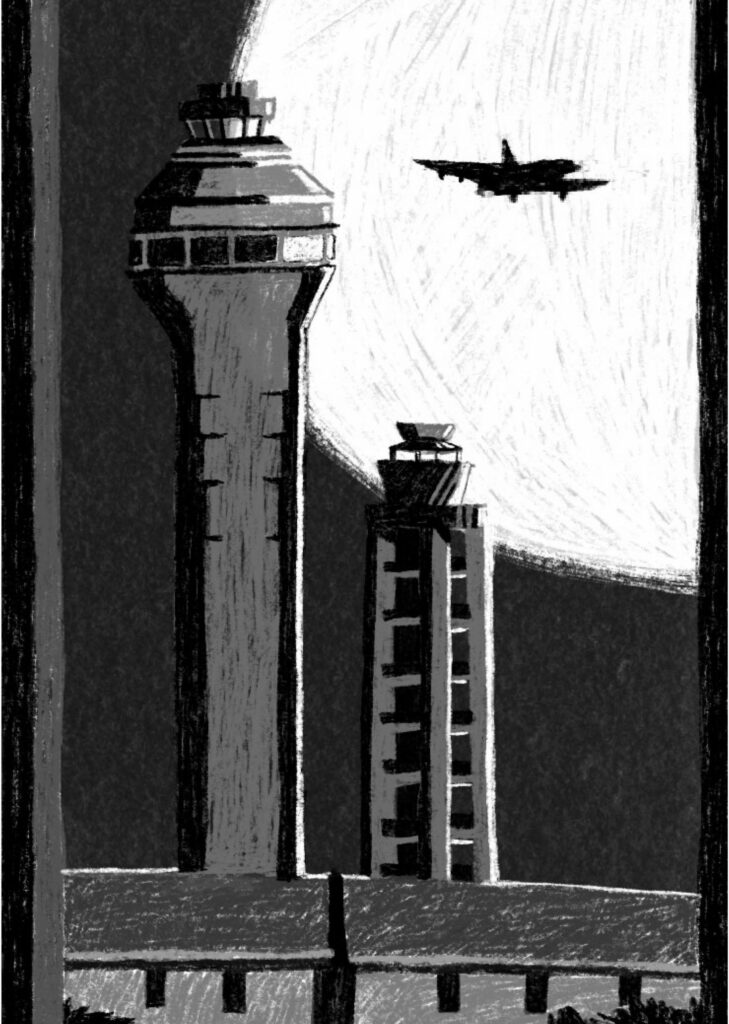

The Haitian mind takes flight in Miami.

Nicole Iu

The strongest parts of the book capture the claustrophobia of political dissidents who wait for the hammer to fall. Mika tries to write but instead finds herself “cowering behind the furniture like an animal being stalked.” She realizes “how hard it is to cheat my body,” which registers the terror that her mind rejects. At times, however, A Knife in the Sky suffers from a lack of subtlety. Although the translator, Katia Grubisic, does a capable job, the prose does not always read smoothly, largely because of an excess of historical exposition in the dialogue. Then there is the matter of characterization. Some figures are memorable, such as Mika’s confidante, Bé, who spends four years with an abusive, closeted husband and steals his glasses as a trophy when she leaves him. Yet Mika herself is at first so righteously defiant, then so horrifically abused, that there is little room for nuance.

When it comes to ethical and psychological complexity, Marie Vieux-Chauvet’s Love, Anger, Madness, a 1968 masterpiece, provides a more compelling portrait of women who negotiate their agency and complicity in the face of Duvalierist repression than does A Knife in the Sky. But that comparison may be unfair, given that Agnant is commemorating a real-life victim of persecution. She dedicates her book to the Haitian feminist Yvonne Hakim Rimpel, a leading figure in the country’s suffragist movement who, just like Mika, was kidnapped, beaten, and left for dead in 1958. Though Rimpel survived the attack, she never wrote again. This fictional version of her is therefore understandably heroic, as Agnant reclaims a voice that was silenced.

While Agnant has steadily built a career over decades, Prophète shot to a new level of fame in Quebec in the summer of 2021. Following the assassination of the Haitian president Jovenel Moïse, Dany Laferrière praised Prophète’s sixth novel, Les villages de Dieu (The villages of God) in Le Devoir and other newspapers as the key to understanding the country’s contemporary political situation. The book follows a young woman trying to survive in a slum where rival gang members distribute favours, negotiate with politicians, and murder one another in the search for prominence. The endorsement worked, and Les villages de Dieu soon sold upwards of 10,000 copies.

Prophète had published her first novel, Le testament des solitudes, fourteen years earlier, in 2007, when it won a prize from the Association des écrivains de langue française. Like all of her fiction, her debut appeared with Mémoire d’encrier, a press founded by the Haitian poet Rodney Saint-Éloi. Now the English version, Blue, has been rendered with remarkable fluency by the decorated translator Tina Kover. And, curiously, it has been released by Amazon Crossing, an imprint of every independent bookstore’s most hated multinational.

This slim text appears as something of a transitional work between Prophète’s earlier poetry and the realism of her current fiction. Certainly, it inhabits the opposite end of the stylistic spectrum from A Knife in the Sky. While Agnant is direct and detailed, Prophète is impressionistic and poetic, with far more regard for imagery than for plot.

The novel tracks the stream of consciousness of a woman in a Miami airport who is returning to Haiti following the funeral of an aunt who had emigrated to Florida. The narrator reflects upon her sense of displacement and the lives of her female relatives from “the blue province,” a region in Haiti’s rural south. Although there is little in the way of linear development, themes include the narrator’s ambiguous relationship with her mother — condemned in the opening pages for having “no real identity to speak of”— and the forces that push Haitian women to migrate. Set a month after the attacks of September 11, 2001, the book is shot through with melancholy. If the Floridian south is “welcoming and inhuman, with light to hide its ugliness,” the blue province is a place where “the rivers, I’m told, have killed themselves, dried up.”

Blue is concerned mostly with the flux of the contemporary experience and the vagaries of memory, and, indeed, it will frustrate anyone hoping for concrete characters or political incisiveness. At one point, the narrator declares, “I have spoken about Marcel Proust far more than I have about my own people.” The reference draws attention to the modernist sense of alienation that runs throughout: even after her return to Port-au-Prince, the narrator insists, “I am as foreign here as I was at the Miami airport.” It also highlights the recurring motif of coffee, which operates as a kind of Proustian madeleine that links past and present. The scent of a terminal Starbucks, for instance, makes the narrator consider the rituals of her childhood, when beans were ground by hand. After her return, her grieving mother “chooses to slice into the silence with a coffee.” As a crop produced in rural Haiti for both consumption and export, coffee paradoxically represents domesticity and globalization, rootedness and movement, homeland and exile.

Like Agnant’s A Knife in the Sky, Prophète’s Blue presents itself as a form of testimony: “I am a witness to the slow death of my land, to its inexorable slide toward a foreign elsewhere, toward the sea, toward abysses near and far.” But where Agnant delves into the grand arc of history — attacking dictatorships and the gendered violence they enact — Prophète is concerned with the minutiae of daily life, the accumulation of small tragedies among sisters and nieces who cannot all secure visas to attend each other’s funerals. Neither approach is more legitimate than the other, of course. Their coexistence signals the diversity and richness of contemporary Haitian literature, with all its Québécois entanglements. One hopes that anglophone readers will have more opportunities to engage with a tradition that has been flourishing in Montreal for decades.

Amanda Perry teaches literature at Champlain College Saint-Lambert and Concordia University.