In January 2010, just as he was finishing a book on the history of social movements in Quebec, Sean Mills decided to go to Haiti. Before he had a chance to leave, the January 12 earthquake struck the country, ending the lives of hundreds of thousands of Haitians, and dramatically changing the destiny of millions of others.

In the wake of tragedy, Haitians in Montreal mobilized, rendering visible all the complex connections between Quebec and Haiti. Leaders of the diaspora successfully pressured politicians to remove barriers to the migration process and organized resources to support and welcome relatives.

Meanwhile, Quebec media relayed images of the devastation, spurring the public to make donations. The strength of the collective mobilization left a deep impression on Mills, and so he set out to write a history of the multifaceted relationships between Haiti, Haitians and Quebec. Moving away from a long tradition of studies that seek to make sense of western influence on Haitian history, Mills endeavoured to shed light on how Haiti and Haitian migrants have shaped a western society.

“At some point in the middle of the project, however, I began to realize that the process of researching and writing this history was having an important effect on me,” he writes in A Place in the Sun: Haiti, Haitians and the Remaking of Quebec. “Haiti is a country that leaves few people -indifferent.”

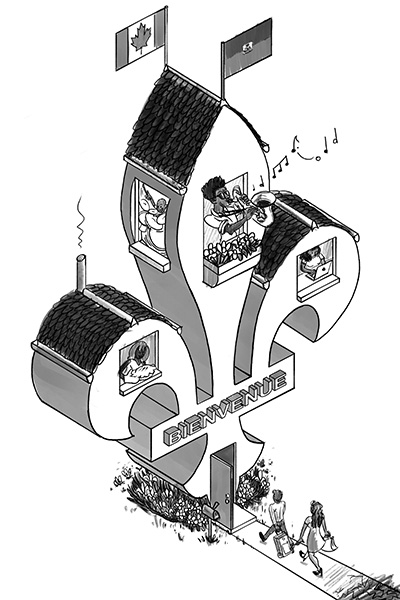

Tyler Klein Longmire

Mills, an anglo Montrealer who is now a professor in the Department of History at the University of Toronto, thus became part of his subject. His engagement with Haitians and with Haiti has transformed his perspectives as a Quebec scholar just like—and that is the main argument of his book—the engagement with Haitians and with Haiti has transformed Quebec.

That claim is bold, and could easily be misunderstood. Indeed, one can point out how certain streams of migration have transformed or contributed to a western society in several ways. In Canada, we usually celebrate immigrant contribution by exalting the life of certain role models. Of course, Haitians have contributed to Canada, because after all, Michaëlle Jean was our head of state for five years, and Dany Laferrière is now the first Canadian to become an Immortal of the French Academy. Several books celebrate this participation of Haitians in Quebec society, drawing portraits of exceptional individuals whose professional successes have left a mark in government, academe, sports, arts or culture.

This individualistic, Canadian dream approach to immigrant contribution is unsatisfying for various reasons. First, it creates blueprints of what success and achievement look like that are, more often than not, unattainable. In a world where black youth desperately need models to project themselves onto, celebrating only those of us who become governor general is both silly and counterproductive. Second, such role model–based narratives are often used to counter those who speak of continuous, systemic anti-black racism in Canada. If a black woman can become Canada’s head of state, everything is possible for all our black youth, right? Finally, insisting on the success of only some immigrant individuals completely erases any impact that collective mobilizations, such as the one Mills witnessed after the Port-au-Prince earthquake, can have on policy, economics, demographics, public discourse and the collective imagination of a country.

Wisely, then, Mills does not fall into the trap of the Canadian dream. He focuses on the symbolic importance of Haiti for French Canada, and on the ways that Haitians in Montreal have both shaped and contested their representation and that of their homeland over the decades. Building on his earlier book, The Empire Within: Postcolonial Thought and Political Activism in Sixties Montreal, Mills shatters simplistic, mainstream understandings of North-South relationships, describes the colonial legacy of Quebecers in Haiti, and shows the responses from Haitians and their allies in Quebec to such colonialism and racism.

Relationships between the West and the rest are typically portrayed as a generous “developed” country that provides aid to the “under-developed” country and selflessly welcomes its immigrants and refugees. This paradigm certainly applies to Canada’s self-image in most of its relationships to the global South, and Haiti is no exception. A Place in the Sun extensively describes how, starting in the 1940s, French-Canadian missionaries settled in Haiti to re-educate its “child-like,” “sexual deviant,” “superstitious” and “primitive” population in desperate need of assistance and tutoring. Haiti hence emerged as a “powerful Other against which ideas of civilization were built,” writes Mills. In his first chapters, he describes the ways in which accounts of such missionaries circulated back into parishes across Quebec, forming an image of Haiti that endures to this day. The durability of such representations is remarkable. Just this April, Radio-Canada broke a story on Québécois police officers who had sexually abused Haitian women and abandoned them with their babies while part of the UN mission to Haiti. André Arthur, a former member of Parliament for Portneuf-Jacques-Cartier and a Quebec City–based radio host, commented that this “hopeless,” “sexually deviant” country populated by thieves and prostitutes and responsible for HIV/AIDS should be recolonized. Despite a public outcry from the Black Coalition of Quebec and the Haitian consulate in Montreal, the declaration was mostly met with a shrug.

I would love to say that this is shocking. But in 2004, Carole Beaulieu, editor-in-chief at L’Actualité, suggested that Haiti become the eleventh Canadian province. That same year, a coup d’état forced Haitian president Jean-Bertrand Aristide from power, and many have pointed since to Canada’s role in that political crisis. It seems that, periodically, Québécois and Canadian elites think of Haiti as their own personal version of Puerto Rico. Mills is absolutely right in stressing how this colonial discourse, originally circulated by the church, has survived the Catholic hegemony over Quebec society.

However, mainstream representations of Haiti are not always so gloomy and, as with most things in Quebec politics, the complete reality is not that simple.

Parallel to the idea of the country as a child, Haiti has also been seen as a brother or a sister society both by French-Canadian intellectuals and Haitian elites who have been living in each other’s countries since the 1930s. Mills explains:

Constructed as the only French-speaking country in the Americas (although the vast majority of its population actually spoke Haitian Creole, not French), Haiti was said to be tied to Quebec by a special bond, one that French-Canadian intellectuals conceptualized in familiar terms. Since the Second World War, Haiti has therefore been central to French Canada’s international presence.

In other words, while the vast majority of the Haitian population, who are Creole speaking, are portrayed as barbaric primitives, some Haitians who could present as francophones have been able to insert themselves into Quebec’s intellectual, literary and political life. Together with some Quebecers—mostly in Montreal—they have used aspects of Quebec’s linguistic nationalism to create a more equal representation of their country, as another “beacon of French civilization” in the hemisphere and as a comrade-in-arms in the fight against Anglo-American hegemony.

This sibling relationship draws on the rich tradition of exchanges between Québécois and Haitian authors and intellectuals, of which Dany Laferrière is the most well known, but not the most representative. It also bridges the exiles of the Haitian Left and some nationalist leaders in Quebec of the 1960s and the ’70s, who used the metaphors of the South and blackness to describe the economic marginalization of francophones within Canada—while often ignoring the marginalization of so many blacks at home. And it has been built, as Mills reminds us, between envoys of the Duvalier dictatorship (1957–86) and some Québécois missionaries and non-governmental organizations, the Canadian International Development Agency, and the Canadian tourist industry, all of which lent legitimacy to the notoriously violent regime by their continuous, active presence in a country that hundreds of thousands were fleeing.

This question of how Haitians are represented illustrates well how experiences of racism are informed by language, class and gender, all of which determine access to schooling and to certain milieus. This is true of Haitians in Quebec but also of diaspora politics throughout francophone countries, where social stratification often follows exposure to French as a language of instruction and a language of prestige, rather than as a mother tongue.

The second part of A Place in the Sun focuses on the Haitian response to the French-Canadian imagination through an exploration of key events of the 1960s, ’70s and ’80s. While Canada was reforming its racist immigration laws and slowly allowing in more people of colour, many Haitians started to flee the Duvalier regime, which became more and more violent and dictatorial over the course of the 1960s. In this first wave of migration—often referred to as a brain drain—were many high–profile political exiles who founded key institutions of the nascent Montreal Haitian community, some of which are well into their fourth decade today. Since the 1970s, this group of exiles has been followed by mass migrations of poorer, more rural, more Creole-speaking Haitians, who experience harsher racism due to their socioeconomic background. Facing housing discrimination and often excluded from Montreal’s downtown cultural life, they have located in peripheral neighbourhoods such as St-Michel and Montréal-Nord, which is one of the poorest communities in Canada.

In the face of shared struggles, powerful cross-class solidarities have emerged among Montreal’s Haitians. Mills forcefully retells 1974’s “crisis of the 1,500,” when Haitians successfully stopped the deportation of as many as 1,500 individuals who had arrived in Canada to escape the poverty and the political repression of Haiti. According to Mills, the campaign succeeded “partly because of [Haitian leaders’] appeals to the conscience of the population and partly because of their ability to position themselves as ideal francophone immigrants for modern Quebec.” In other words, some leaders have been able to play on their personal francophone “privilege” to organize on behalf of more vulnerable immigrants.

This strategic appeal to Frenchness has often been repeated in the history of Montreal’s Haitian community. Mills writes that Laferrière consciously adopted the strategy to create and promote his ground-breaking literary success, How to Make Love to a Negro without Getting Tired. According to Mills, Laferrière’s instant popularity needs to be explained by his ability to toy skilfully with the trappings of Québécois nationalism. Mills explains the historical proximity of some Haitian leaders to the Parti Québécois in a similar fashion.

From the vantage point of history, one can see that such a strategy comes with a price. Engaging with linguistic nationalism has allowed some Haitian leaders to bring some stories to a broader Québécois public with great success. Yet the broad penetration of this image of Haitians as model francophones in the collective imagination may have complicated equally important issues—such as employment and housing discrimination, police brutality, the racial and gender pay gap, illiteracy, chronic political and media under-representation, and endemic poverty. To this day, these challenges rarely get the political attention they deserve. Such a discourse may have also contributed to the two solitudes of Canada between French-speaking and English-speaking blacks in Montreal, complicating some forms of organizing against enduring systemic anti-black racism in the city.

Of course, not all Haitian activism has followed this path. Mills recounts how “in the face of ongoing racial discrimination, Haitian activists, like other social groups with whom their struggles were at times intertwined, worked to open up a new space where their voices could be heard and their perspectives understood.” Over the decades, many have convinced those on the Quebec left of the ills of aid and traditional missionary work, progressively transforming the ethics and practices of international cooperation NGOs. Others have drawn the attention of the Québécois feminist movement to the specific challenges facing black women, and Haitian feminists have organized collectives to work at the intersections of the different oppressions affecting their lives. Others yet have challenged systemic racism in the job market, and in the taxi industry more specifically. “In doing so, they contributed to the development of a counternarrative of Quebec society,” says Mills. Haiti, and Haitians, have participated in remaking Quebec.

Haitians in Montreal, their children and their children’s children are still today, every day, remaking Quebec. Some are raising awareness about the involvement of the Canadian mining industry in Haitian politics. Some are lobbying elected officials to boycott the Dominican Republic for human rights abuses against its citizens of Haitian descent. Some are mobilizing to end police brutality and reform the criminal justice system. Some are denouncing their under-representation and misrepresentation in mainstream Quebec media. Some are building alliances with the emerging generation of indigenous leaders and anti-Islamophobia activists to fight racism.

There is a tendency in Quebec and across Canada to look to the United States for models of black leadership and black identity. There is a danger in this. Although black diasporas around the world share a common history and many struggles, they also interact with different institutions and come from different traditions of organizing. One must be careful not to let the giant of African-American history erase other ways of being black in North America, such as those of Haitians in Quebec.

Many things have changed in Quebec since the 1980s—where A Place in the Sun ends. Perhaps most important, minorities have had an arguably lesser, and at least a very different, place in Quebec nationalist circles and in language politics. Individual French-English bilingualism has also increased, so blacks in Montreal can join forces in ways that perhaps would not have been possible before. Yet, although the historical context has evolved, this rising generation of Haitian activists is definitely following in the footsteps of the founders of those movements and institutions that Mills so vividly describes. To move forward more wisely, the new generation needs to understand its local contexts and local histories and the legacies on which it is building.

As a Quebec scholar and as an activist of Haitian descent, I make sense of who I am and of the work I do in relation to the history of the communities to which I am bound. As such, Sean Mills deserves great credit for his contribution to the story of how my generation has emerged.

Emilie Nicolas is a PhD candidate in anthropology at the University of Toronto. She is the co-founder and president of Québec inclusif, a movement that fights racism and the social exclusion of minorities in Quebec society.