Based on the marketing copy on the back cover of Nicholas Herring’s debut novel, readers might expect a story like Michael Crummey’s Galore : a lush, disconcerting, and disorienting narrative of magic realism with a distinctly Atlantic Canadian flavour (of the early Newfoundland cod fishery in Crummey’s case, and of the contemporary Prince Edward Island lobster fishery in Herring’s). But Some Hellish is nothing of the sort. It is a work of immediate, tactile realism, wrapped around a single hard kernel of fantasy.

The central event of the novel — the inexplicable survival of a middle-aged lobster fisher, lost overboard while out of his mind on LSD and rescued hale and hearty after eight days — is bookended by convincing depictions of life in a small fishing community. From the stench of diesel fumes belching out of a Cummins engine, to the whine of an angle grinder scouring barnacles off a fibreglass hull, to the raw hands and stiff backs and endless hours spent mending gear and baiting traps, this novel is rank with the salt-and-old-bait authenticity of the typical Maritime wharf.

The protagonist, referred to only by the surname Herring — the same as the author’s — is “an awkward barrel of a man,” red-faced and chapped from the dual plagues of alcohol and psoriasis, with large, dry hands “as white and as stiff as bowling pins.” His house and yard, his financial credibility, and his marriage are all vexed by a creeping rot. Although he craves “a true and real companionship,” he refuses to do the work of maintaining relationships. Instead, he distracts himself with moonshine, hashish, shatter, and psychedelics. The only object that merits his active concern and care is his boat, the Marcelina & Marceline, named as an afterthought for his two daughters several years following its first launch.

There is one other constant in Herring’s life: a sense of rage that has haunted the men of his family for generations, “driving them to drink or to preach.” That “stark and forsaken” anger adds to his insufferable reticence, interrupted occasionally by his sharp tongue. He has the reputation of a man “as slippery as his namesake.” His manner suggests “something untamed, and perhaps even despicable.” His wife, Euna, who left him after he cut a hole in their living room floor and refused to explain himself, calls him a “dickhead” for his senseless confrontations.

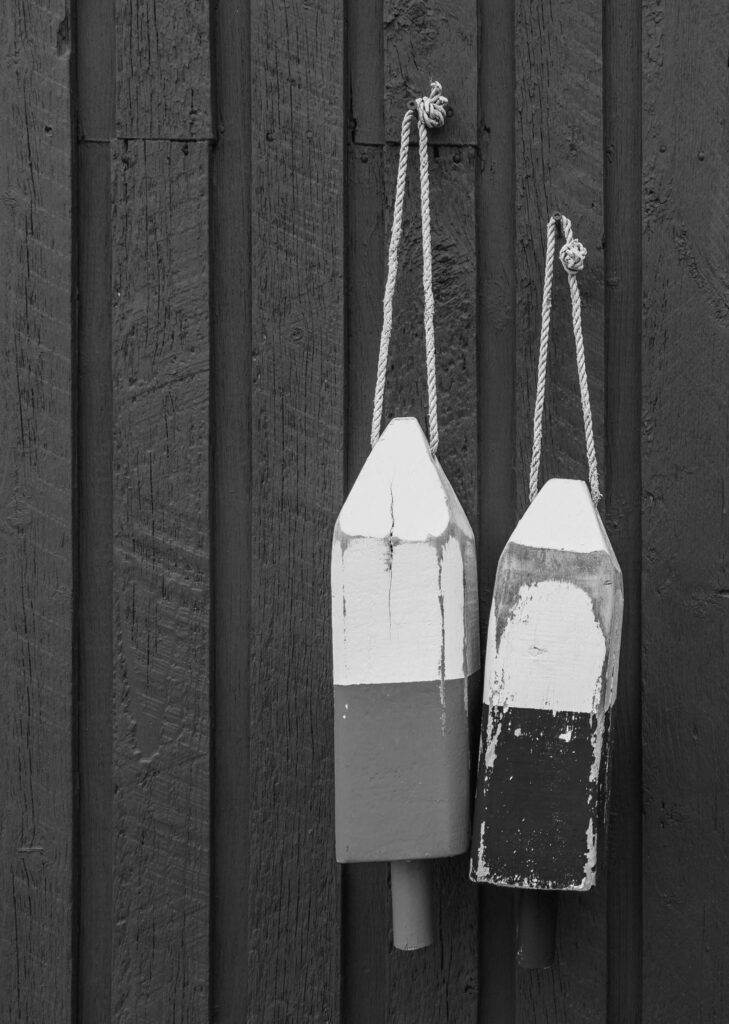

Rank with salt-and-old-bait authenticity.

Scott Walsh; Unsplash

His neighbours and fellow fishers think even less of him: “Fuck Herring. What does he know?” says a bar clammer behind his back, and another lobsterman tells him to his face, “Nobody likes you, Herring. Yer a halfwit.” His deckhand’s mother asserts that “he’d skin maggots if he thought there was money in it” before advising her son to give his boss a wide berth.

Cursed with an acute awareness of his own shortcomings, yet unable to redress them, Herring laments his state while considering a broader decline. “There used to be twelve types of fish here. Now there’s one,” he says. “Fishing’ll be dead in about a decade. And what’s else, you know, I have no peace in me, at all. I mean, none, no peace.” For Herring, “every goddamn day” is a battle: “Kill or be killed. And it just doesn’t have to be this way, eh, does it?”

Just as the loss of profitable fishing stock has driven the community into antagonistic competition, Herring sees his life stripped of the joy and meaning that would allow him to thrive. In his more lucid moments, he is aware of “a future version” of himself “who was very much dead and gone, even thoroughly forgotten.”

Following his ordeal at sea, Herring finds himself a changed man, without knowing exactly who he has become or how to go about living with his new consciousness. Sober for the first time in years, uncharacteristically loquacious, and finally free of his primeval anger, he sloughs off the hard carapace of his former self to reveal something softer, more fragile and vulnerable, as if “he had been rewarded, or more accurately, gifted with, not only a bit more of life, but a bit more of what seemed to be a fresh life.” Herring works to repair his relationships and open himself to new perspectives; he freely gives apologies and explanations where once he offered only silence. But this is no neat and tidy redemption arc. The world around him remains as messy and intractable as the sea in an east wind. As Herring learns to recognize and act on his deepened sense of compassion, he meets with unexpected consequences.

Some Hellish is full of startling juxtapositions. Setting disgust cheek by jowl with delight, for instance, the author notes the smell of “cigarettes and manure and mould” just before the protagonist enjoys some homemade hot biscuits with butter. Later, an expensive and controversial act of radical compassion results in violence and attempted arson. By contrast, the unsolicited peace of Christ comes to lie, fully acknowledged, on the soul of an unbeliever. The events of Herring’s life — and of the community’s — are brutally multi-dimensional, often captivating and repulsive at once.

Readers might feel a little unmoored, like the main character himself, who eschews his expensive GPS in favour of a more elusive fisher’s instinct as events lap over each other like waves, relentless and ungovernable. Sometimes we’re left to drift mid-paragraph, in search of a buoy that may never appear. Characters’ motivations remain murky — even to the characters themselves — and the only sense of direction comes from their confused perspectives as they navigate relationships. (Aside from Herring, the story occasionally follows his deckhand, Gerry, the closest thing to a friend the protagonist can claim.) Even the uprisings of the natural world — hurricanes, snowstorms, and “the grey belt of the water encircling the world”— sway the outcomes of human affairs in unpredictable ways.

As the first Maritimes-born author to win the prestigious Atwood Gibson Writers’ Trust Fiction Prize, Nicholas Herring has managed to evoke a visceral nostalgia for the East Coast while offering an honest portrait, warts and all, of a region whose future is bound up with the effects of climate change, overfishing, and poor education. Yet the final scene, as if abstracted from the rest of the story, leaves readers with the sense that the protagonist has found his bearings. The novel’s expression of hope for a renewed community, freed from exploitation and division, is one that many Canadians can appreciate.

Carolyn Ellis works as an offshore snow crab and shrimp fisher in the Atlantic provinces.