Has anyone noticed how women are driving so much innovation in the writing of history these days? For five years in succession, a woman has won the Cundill History Prize, awarded annually by an international jury of scholars gathered by McGill University to honour “the best history writing in English.”

These five women deserve their honours. There has been a lot of good historical writing by men, as well as by women, among the recent Cundill short lists and finalists. But the winning books are changing what’s long been the standard historical voice. Their authors display a distinct pleasure in the craft and a willingness to share personal engagement with their subject matter. The edifice of impersonal scholarship and objective history is shaking.

Perhaps male scholars feel more constrained by the gravity and authority sometimes associated with the profession of history. At least some women, no less scholarly, seem more willing to play with form. That’s especially the case with the 2022 Cundill winner, Tiya Miles. Miles has abandoned the faith that serious scholarship must be presented by an invisible author applying defined historical methods to a body of written documents. She calls herself a “public historian” and studies marginalized people through marginalized fields of research: material culture, genealogy, oral history, family lore. A generation ago her subjective, emotional, empathic response to the past might have been dismissed as “not history” or “sentimental.” Now it wins her shelves of prizes, and recently it secured her a full professorship at Harvard. The boundaries of the genre are truly expanding.

Among the recent Cundill finalists, Vladislav Zubok, the only man of the three, cannot help but seem the upholder of orthodox historical topics and methods. Indeed, his book Collapse: The Fall of the Soviet Union is distinctly in the “great man, great power” genre of classic political-diplomatic history: nearly 600 pages carefully constructed through the scrutiny of meeting notes, position papers, economic plans, and diplomatic exchanges. And there’s barely a woman in sight.

Still, Collapse is an impressive history, and Zubok does open with a flash of personal engagement, which echoes through the rest of the story. In August 1991, as an academic in Moscow and an enthusiast for Mikhail Gorbachev’s reforms, Zubok earned a brief research fellowship in the United States. He returned after four months, but, as he writes, he never got back to the U.S.S.R. It no longer existed.

Zubok doesn’t offer much more of his own first-hand testimony, but he does keep the reader aware of all the shocks and dislocations experienced by any Russian who was young in the 1980s. There was a glimpse of possibility late in the decade. Then came the upheavals of 1990–91 and the disintegration of the mighty Soviet Union. What followed was economic collapse, impoverishment, the emergence of shocking income disparities, a staggering drop in life expectancy, the plundering by “oligarchs,” and gradually the horrifying slide down to Putinism — and all of it under the complacent scrutiny of Cold War triumphalists in the West. Since February 2022, Russia has squandered any claim to sympathy, but Collapse commands empathy for the Russian people. They have lived through much, and there is more to come.

Three powerful depictions of the past.

Pierre-Paul Pariseau

Zubok explains the fall of the Soviet Union in two words: Mikhail Gorbachev. He authoritatively sweeps away Western conceits that “Reagan won the Cold War.” As a matter of fact, he writes, “Western governments were surprised and dismayed by the Soviet Union’s destabilization, and then disintegration.” Zubok is equally dismissive of the theory that the West’s aggressive expansion of NATO is what drove Russia back to totalitarianism. The decisive cause was in Moscow.

Gorbachev, in Zubok’s analysis, was above all a Leninist. It was Lenin’s complete works that he turned to for guidance at every crisis and turning point, and he shared with the first Soviet leader a limitless confidence in revolution: move fast and break things, and all will work out for the best. Glasnost (openness) and perestroika (restructuring), the twin forces that killed the Soviet Union, were the products of Gorbachev’s extraordinary optimism.

Gorbachev knew — everyone did by the ’80s — that the Soviet command economy had become a disaster. He started to smash it, confidently expecting that handing economic responsibility down to local managers, workers, and young people inspired by freedom would quickly produce a cooperative socialist paradise. Instead, most of the beneficiaries — gangs of party bosses, regional bureaucrats, aspiring entrepreneurs — plundered state resources. The result was a modern kleptocracy, much of it rationalized by economic doctrines preached by neo-liberal shock-doctrine consultants from the West. Meanwhile, despite the worldwide acclaim Gorbachev had achieved, Western governments did not believe in his promise of a free, market-oriented, and unthreatening Soviet Union. They consistently refused to underwrite the “Soviet Marshall Plan” that might have reinforced Gorbachev by providing some economic uplift for citizens of the bankrupt federation.

Gorbachev’s plan on the political level was equally optimistic and bold. He calculated that if he devolved the powers of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union down to client states and internal republics, they would reform themselves democratically into a community of shared socialist aspirations. He believed they might found a “Common European Home” with their neighbours across the vanished Iron Curtain. What he actually unleashed was a flood of new states determined to get free of their old oppressor as fast as possible — and these were often led by opportunistic former party bosses turned ethno-nationalist dictators.

In the Russian Republic, previously the heart of the Soviet Union, Boris Yeltsin seized Gorbachev’s offer of devolution and local elections and used them to make himself an authoritarian populist leader. From the new Russian parliament, a few blocks from Gorbachev’s Kremlin, he worked to reduce the general secretary to impotence and meaninglessness. Preaching Russian nationalism, yet needing allies against the centre, Yeltsin endorsed the complete independence of any republic that sought it, even agreeing that the status of Crimea, with its notable Russian population, should be settled between the Crimean people and the new Ukrainian state.

Had Gorbachev maintained the U.S.S.R.’s police controls while pursuing radical market liberalizations, Zubok suspects, he and his program might have made more headway. Most Russians, he argues, would have accepted a strong Soviet leader who delivered a better economic future over promises of democratization and decentralization. But Gorbachev had another, even more surprising, more admirable — and quite disastrous — trait. He absolutely refused to rely on force. In 1990, the general secretary could have ordered the Soviet army, the KGB, and the apparatchiks of the Central Committee to toss all of his rivals and critics into jail and to have Yeltsin shot.

It was chaos, not blood, that rose around him, while more ruthless men took over everywhere. Zubok climaxes his book with the failed coup of August 1991 that killed the Soviet Union. Gorbachev’s own apparatus — the army, the KGB, and the Communist Party — desperate to salvage something from the wreck of all they knew, finally moved to confine him. They also sent tanks to show the unruly Russian parliament that the Soviet Union would endure.

As the tanks rolled through the streets of Moscow, democrats, decentralizers, intellectuals, and members of parliament were sending calls of farewell: they assumed that by morning they would all be dead or languishing in KGB dungeons. But the nightmare legacy of Stalin seemed to render even his heirs and acolytes incapable of turning their guns on fellow citizens.

This proved to be Yeltsin’s moment. He climbed on a tank and dared the coup leaders to shoot him. When they did not, he swept them away. Yeltsin presented himself as the defender of the constitution, the protector of Mikhail Gorbachev, and the standard-bearer of democracy. He seized personal power and swiftly jailed most of his rivals, breaking all the constitutional limits on his Russian Republic while delivering most of the remaining powers of the Soviet Union to himself. Yeltsin would win re-election as the man of the people and tool of the oligarchs and eventually pass his mantle to Vladimir Putin.

Zubok dedicates Collapse “to all reformers.” Gorbachev was undoubtedly one of those, but Zubok lays at his door the origin of most of the evils that have followed in the subsequent decades. History has never been a morality play about the inevitable victory of freedom and democracy, he concludes. “This amazing story,” he writes bleakly, “should help us prepare for sudden shocks in the future.”

Like Zubok, Ada Ferrer also must contend with “great man, great power” narratives in Cuba: An American History, a 500-year survey that’s as long as Collapse. Anticipating a mostly American readership, she employs a narrative device that continually places Cuban history within the context of the United States: Cuba from Columbus to Castro, but also from Teddy Roosevelt to John F. Kennedy. At times, her search for Cuban-American connections — including exiles doing menial work in New York or Miami — seems forced. And all those Americans who have plundered the island nation for the benefit of themselves and the U.S. hardly demonstrate “dense networks of human contact.” Yet the connections Ferrer draws do serve to emphasize the huge, almost entirely malign impact one country has had on another.

By the nineteenth century, Spain’s largest Caribbean colony was becoming a monoculture based on sugar and forced labour. Compared with other Latin American countries, Cuba was slow to reject both slavery and Spanish rule, because plantation owners preferred feudal domination to an independent nation with a liberated Afro-Cuban workforce. The high point of shared Cuban-American interest came in the late nineteenth century, when the white oligarchies of the Reconstruction South and of Cuba made common cause. American capital poured in to shore up slavery and then peonage.

In 1898, with slavery finally ended and the independence movement about to defeat the occupying Spanish army, the U.S. declared war on Spain and swiftly appropriated the Cubans’ victory. As the new ruling power, Washington imposed a constitution that gave the United States ultimate sovereignty and a free hand to intervene militarily when it saw fit. So began the sequence of unstable democratic regimes and strong dictatorial ones that defined Cuban political life in the first half of the twentieth century.

Ferrer recounts Fidel Castro’s popular revolution in lively and compelling fashion. But with Castro in power, her “American history” of Cuba may put too much emphasis on those issues that are of interest to American readers: the floods of refugees, Cuba’s alliance with the Soviet Union, Castro’s military support for revolutions elsewhere in the world. Her earlier chapters establish very clearly why Cuba was always poor, colonized, dispossessed, and unequal. The later ones might have acknowledged aspects of Cuba that are less welcome in American eyes. Under the endless embargo, Cuba is still poor. But life expectancies now closely match American ones. Cuban doctors and pharmaceuticals stopped COVID-19 in its tracks, they keep the infant mortality rate low (one-eighth that of the U.S.), and they provide medical outreach to forty other countries. Cubans may not be free, but the Castro years are the only extended period in the past five centuries when the island has not been the colony of a foreign power. Indeed, the old adage of Canadian cultural nationalism —“It’s the State or the United States”— might be adapted to “It’s the Castro state or the United States.”

Ferrer does not aspire to a detached, objective recitation of political history in the classical mode. Her opening page declares, “I was born in Havana between the Bay of Pigs invasion of 1961 and the Cuban Missile Crisis of 1962.” (She and her mother left for the U.S. as refugees ten months later.) She does not offer much more of her own family’s story, but she makes the national history a personal one nonetheless, with peasant perspectives regularly balancing those of conquistadors and dictators. Her inclusion of Indigenous people, slaves, folk artists, soldiers, women, and others enlivens every chapter with skillfully shaped vignettes of individuals from the margins: the boys who, in 1612, introduced Cuba to the miraculous statue of the Caridad del Cobre, Cuba’s patron saint; Antonio Maceo, the black Afro-Cuban farmer who became a general and grand strategist of the wars of independence; Celia Sánchez, the middle-class woman turned underground organizer and early ally of Castro; and many others. Ultimately, Ferrer makes Cuba a brilliant example of a kind of political history that does not feel dominated by great-man politics.

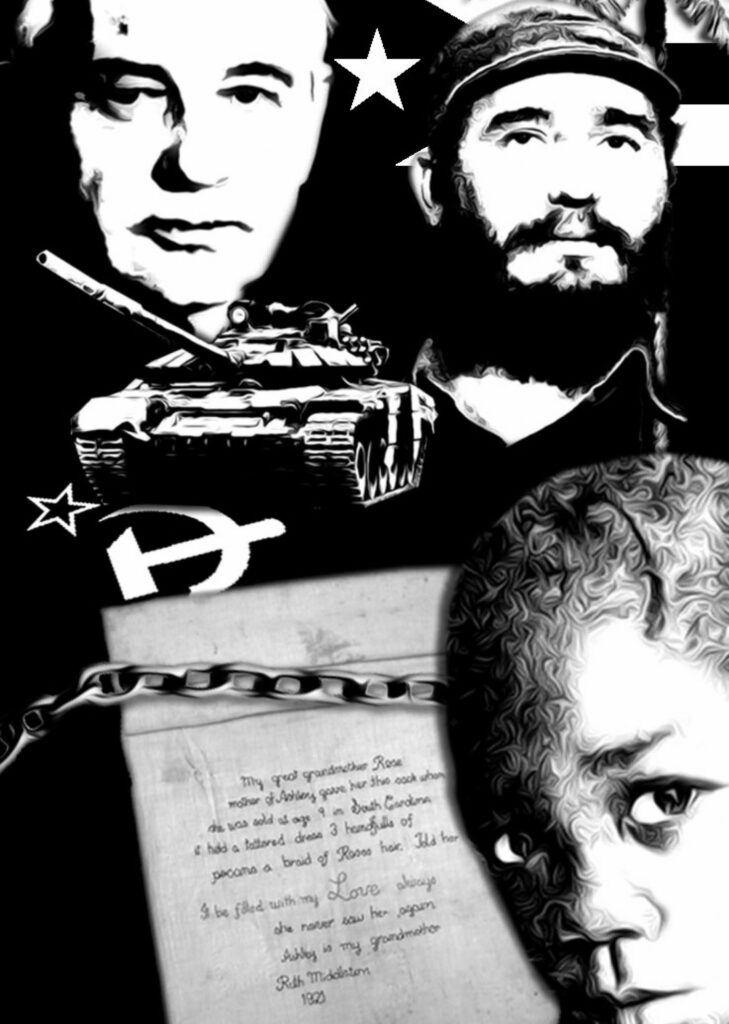

with All That She Carried: The Journey of Ashley’s Sack, a Black Family Keepsake, Tiya Miles launches into an experiment in narrative perspective even more personalized than Ferrer’s. She notes that historical study of the marginalized requires an “attentiveness to absence as well as presence,” and her book is centred on a gaping absence. In 1852, Ashley, an enslaved nine-year-old girl in South Carolina, was sold to new masters. Her mother, Rose, never saw her again. But before the slave trader took the daughter away, Rose packed a sack to help her on her journey. The sack survives, along with the story that a granddaughter of Ashley’s embroidered on it a century ago:

My great grandmother Rose

mother of Ashley gave her this sack when

she was sold at age 9 in South Carolina

it held a tattered dress 3 handfulls of

pecans a braid of Roses hair. Told her

It be filled with my Love always

she never saw her again

Ashley is my grandmother

Rose Middleton

1921

The sack, currently housed at the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture, in Washington, serves as both protagonist and touchstone in Miles’s book.

Miles set out to write a history of an event for which almost no paper record survives. Instead of archival documents, she relied on “traces.” The sack itself is carefully assessed for authenticity by the techniques of material culture studies; it is viewed through elaborate traditions of sewing, embroidery, quilting, and fabric making in Black America. Miles considers slave memoirs and oral testimonies from survivors of other abductions and separations. She mines the scant genealogical traces that do exist from antebellum South Carolina, until they eventually yield up the sole Rose-Ashley family pairing. And the dates fit.

A deep pondering of each of the items Rose put in the sack itself includes a long examination of the history of pecans in American slave culture — and even incorporates some recipes. Through intense scrutiny of the geography of slavery, both urban and rural, Miles scrapes up a startling amount of detail about a mother and a daughter who yet remain almost entirely unrecorded. She frequently circles back to this fundamental absence in her story, taking the reader into a deep consideration of what such a separation must have meant to a child and a parent. And of what kinds of civilization could so routinely practise such abominations.

Miles’s research is scrupulous, her interpretations always linked closely to the evidence. But her book’s aim is to break a reader’s heart, to guide one to imagine, to weep, to pound the desk, to look into the abyss. This work is the furthest thing from detached, objective, or “scientific” history. Not long ago, it might not have been accepted as history at all. This year, the Cundill jury thought it was the best history book published in English anywhere in the world.

The Cundill jurors may themselves have been perplexed at how far they were reaching beyond traditional understandings of historical writing in honouring these three works, not despite but because of their transgressions against scholarly dispassion. Their citation of All That She Carried, for example, declared that it has “the narrative propulsion of a novel.” Similarly, the historian Karen Dubinsky, writing in the March 2022 issue of this magazine, argued that Cuba has “the narrative power of fiction.”

Be clear, though: these books are not fictions. That’s not where they derive their power. Remember, too, that non-fiction writers have been exploring techniques of narration since before the novel was invented. Effective narration continues to be one of the hallmarks of literary non-fiction. That historians are learning to pay attention to such skills should not mislead any critic into thinking it a compliment to write that a history reads “like a novel.”

Christopher Moore is a historian in Toronto.