The New Testament scholar James L. Resseguie described the Book of Revelation as having a master plot that depicts the deep spiritual struggles of seekers on the path toward a promised land. That quest is echoed in the title of Michelle Syba’s debut collection, End Times, which follows both Christian and non-religious protagonists as their beliefs are tested and their lives transformed. The author herself grew up in a Pentecostal home in Toronto before losing her faith. Now a literature professor at Dawson College, in Montreal, she writes with acumen and grace about the human desire to find meaning and connection — whether through sacred or secular means.

The seven nuanced tales in End Times feature several characters who adhere to a literal interpretation of the Bible, but the common assumptions about fundamentalists are largely absent. None of the Christian protagonists is fixated on hot-button issues like abortion or queer identities. Instead, the author gives us idiosyncratic miniature portraits of individuals trying to go about their lives. In “Matsutake,” Syba depicts an aging woman, Sonia, and her keen talent for finding and harvesting wild mushrooms — a hobby informed by questions of faith. “The important thing is a positive identification,” the forager says. “If you have even a tiny doubt that it’s edible, leave it alone. No room for doubt!” Pavla, in “A History of Prayer,” hails from Soviet-era Czechoslovakia and questions her prayer group when they call mask mandates oppressive. And in “Fearfully and Wonderfully,” a teenage girl turns to Christian zeal as a way of coping with the trauma of sexual abuse.

The unnamed Vancouver mother in the titular “End Times” is arguably the most pious of Syba’s personages. In the born-again woman’s belief system, hell represents “loneliness and confusion,” a kind of existence mirrored in the trials of her life. She once lived under a repressive regime, then moved to Canada, became a widow, and suffered through an abusive second marriage that ended in divorce. After so much turmoil, faith has given her a sense of clarity. All she wants now is for her opioid-dependent adult son to share in her spiritual illumination.

The lucid state doesn’t last. Following an unhappy turn of events, she is utterly dismayed when she realizes she has been kept in the dark. “Jesus did not tell her that Matthew was high,” she reflects. “Jesus who knows everything.” Loneliness and confusion overwhelm her, and the ground beneath becomes meaningless. She then closes her eyes — perhaps accepting, perhaps succumbing to the darkness — and feels the sun upon her. In the siren of an approaching ambulance, she thinks she hears “a new note emerge, a more expansive pulsation” that evokes Psalm 98, in which “the mountains rejoice and the floods clap their hands” for God, who has openly shown his righteousness by redeeming Israel.

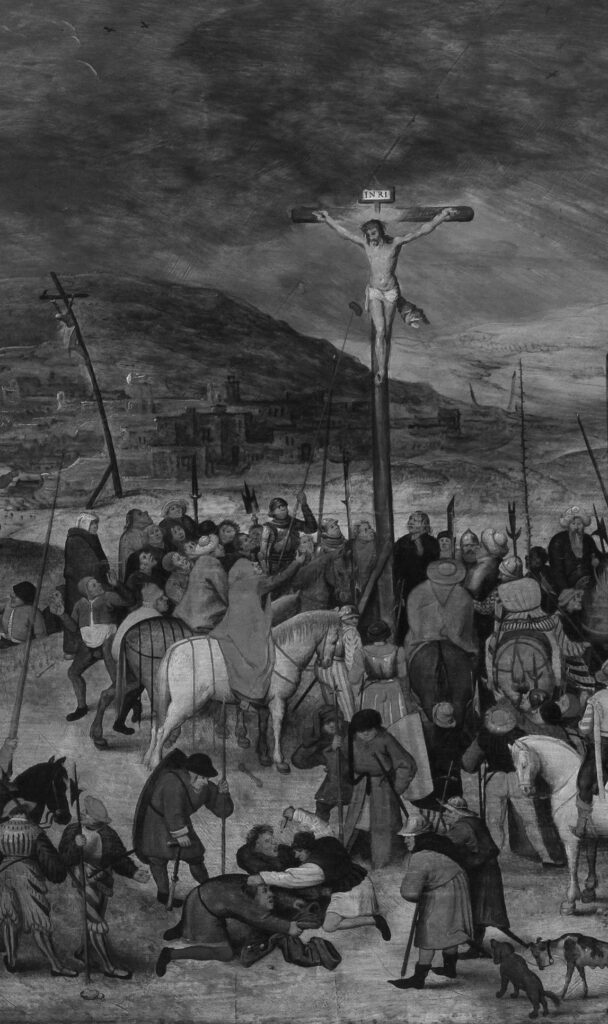

She studies Pieter Brueghel the Younger.

Pieter Brueghel the Younger, The Crucifixion, C. 1617; Philadelphia Museum of Art

Syba’s portrayal of non-religious characters and their experiences is equally meticulous. In “The Righteous Engulfed by His Love,” the protagonist, Ben, is an atheist doctor with an apparent indifference to the state of his apartment: full of “maltreated designer furniture, the LC4 chair covered in jackets and junk mail, the Togo sofa flecked with crumbs.” He also has something of a mean streak: though he acknowledges the intelligence of his boyfriend, Carl, he looks down on the man’s religious convictions, compares him to a child, and concludes that, as an evangelical Protestant, he must also be a self-hating gay man. Ben is oblivious not just to the mess in the apartment but to his partner’s complex interior life.

Syba concludes the protagonist’s story with mystery and irony. When the senior pastor from Carl’s church lays hands on Ben and declares, “Your faith has made you whole,” the non-believer suddenly feels the air above his head pulse, “as if beaten by the wing of an immense bird.” He then sinks into a state of paralysis, ensconced in “a vast sentient net, one that had tracked his past and numbered his heartbeats, and whose operations reached far into his future.”

Each story in End Times asks whether faith or the lack of it makes for a meaningful life. “For What Shall It Profit a Man?,” which closes the collection, explores that question most overtly and exhaustively. The central figure, Beth, is convinced the church taught her to avoid secular knowledge. “I had once feared the world’s empty pleasures and ghastly consequences,” she explains. “Now I wanted to understand how the world worked.” A humanist way of life, she hopes, will give her the tools she needs to satisfy her curiosity.

In her project to know things rationally, Beth chooses to study art history, focusing her doctoral work on the realist paintings of Pieter Brueghel the Younger. Her dream of becoming a professor, however, fails to come to fruition, and she takes on work as a corporate consultant to earn a living. Although she claims to be well-suited to her work and to enjoy it, she sounds weary of all the “spreadsheets and PowerPoints and endless graphs promising robust growth.” When her husband asks if her life is better now that she’s no longer a fundamentalist Christian, she answers with a definitive “Of course.” The response, however, feels less than convincing.

Beth’s dissatisfaction manifests as the need to meddle in the life of a devout pregnant girl named Martha. The mature woman tries to persuade the teenager either to have an abortion or to give the baby up for adoption so that she can go to university and pursue her dream of becoming a teacher. That, surely, would lead to a more satisfying life than being stuck as a mother at such a young age. The irony is that Beth herself desperately wants a child but is unable to conceive. When she eventually experiences a personal crisis — the result of a series of unsound decisions — it becomes clear the secular humanist way of life is no more a guarantee of contentment than that of the Christian fundamentalist.

Aside from Miriam Toews’s fiction and K. D. Miller’s short story collection All Saints, which delves into the intertwined lives of members of an Anglican church, examples of literary fiction featuring complex characters defined by their relation to Christianity can be hard to find. Syba’s compulsively readable End Times offers a rich exploration of religious faith and its absence. It is a worthy addition to a small but fascinating genre.

Andrew Torry is a writer and curriculum designer in Calgary.