Not far from our North Vancouver home there’s a stand of old-growth Douglas firs that I first read about in Randy Stoltmann’s Hiking Guide to the Big Trees of Southwestern British Columbia, from 1987. Stoltmann, whom I met on a few occasions before he died in a backcountry skiing accident in 1994, tracked down and measured humongous coastal trees. In advocating for their protection, his guidebook, published by the Western Canada Wilderness Committee, provided statistical information and the location of several giants.

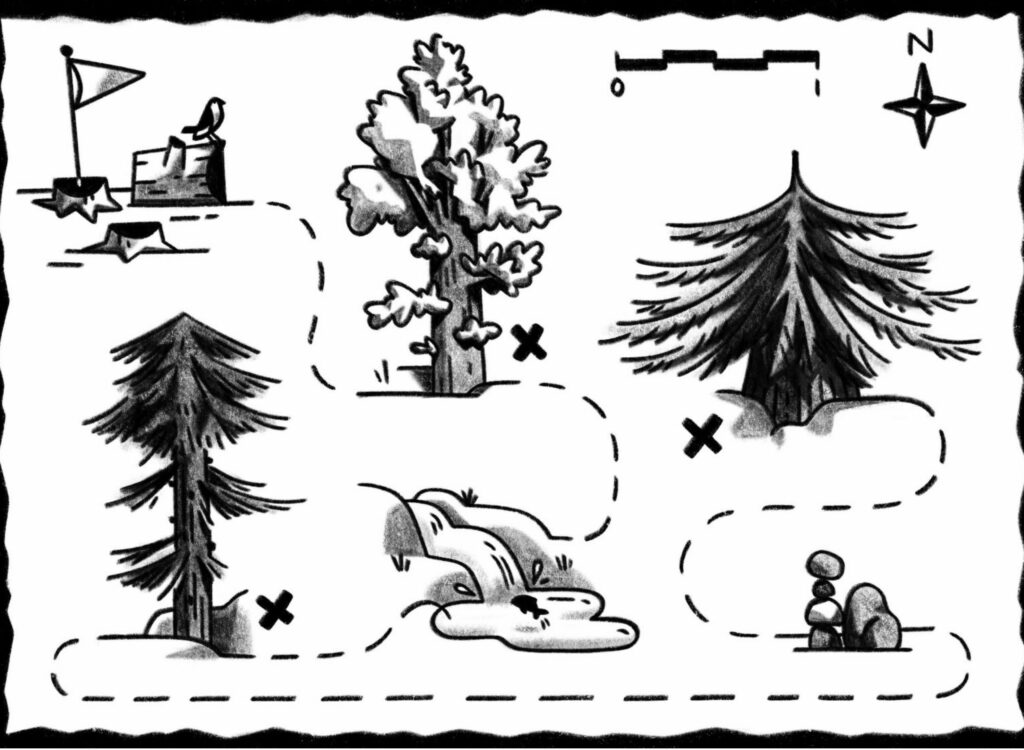

Heeding Stoltmann’s description that “the severity of the terrain is such that only experienced off-trail hikers should venture there,” I pressed my friend Peter, a skilled outdoorsman and a professional hydrologist, to help me find the way. A tiny opening became — like a cave in a Murakami novel — the portal to a cloistered and mysterious place. We clambered up a creek bank, tugging at roots and limbs for purchase. The terrain levelled out, and, sure enough, we soon found ourselves peering up at a beautiful cluster of Douglas firs that had somehow escaped the logger’s axe in the late 1800s. These majestic trees dwarfed the spindly, second-growth cousins scattered beyond (Stoltmann’s measurements were sixty-one metres tall and more than two metres in diameter). At some point, persons unknown — but with the blessing of the District of North Vancouver — had inserted metal “heritage tree” markers into the bark. Though a neighbourhood of luxury homes was but a few hundred metres away, we could have been on the wild west coast of Vancouver Island.

A decade after my first visit, I returned in July 2023. It became obvious that there were now plenty of “experienced off-trail hikers” out there; the vast majority had found the place via social media and not some aging guidebook. A handmade sign read “Trail to Heritage Trees closed due to landslide,” but it hardly seemed to matter; well-pounded trails led every which way up and down the creek. The soil around the delicate root systems had been churned up and a pair of climbing ropes dangled from the limbs of a particularly lofty tree. When I posted the photo on Facebook, a friend of mine who’d grown up with Stoltmann in West Vancouver offered that maybe it was a sign of “gentrification of the forest, the answer to Vancouver’s housing crisis.” Further research revealed that several months prior, a group of ill-prepared hikers looking for some old-growth forests had been plucked from a gully by North Shore Rescue. Transcendence is seldom attained when you’re picking up plastic bags filled with dog poop.

I was dismayed.

Searching for post-worthy nature in the age of social media.

Gwendoline Le Cunff

Before the internet, esteemed writers like E. Annie Proulx, Gretel Ehrlich, Barry Lopez, and Wade Davis described glorious natural spaces that were often at the ends of the earth. Now, if you have the time and money, you can explore the far corners of our planet within — what, seventy-two hours of flight and ground travel? Robin Esrock, another writer from British Columbia, has written a series of best-selling travel guides based on the Jack Nicholson movie The Bucket List. Once a list is made, it seems, there are strivers out there who will want to work their way down it.

Stoltmann’s text, with its list of big trees, figures largely in the story of Amanda Lewis, a burnt-out book editor who goes on a quest to find forty-three of British Columbia’s biggest — or “Champion”— trees. Tracking Giants could have been written only in this province, where forests are compared to cathedrals and yet ancient trees are cut down to make expensive guitar bodies. Where books like The Power of Trees, The Golden Spruce, and Finding the Mother Tree sit atop bestseller lists for months on end. Where Vancouver’s Stanley Park and Vancouver Island’s Cathedral Grove aren’t far removed from the industrial tourism of American national parks that was first decried by the legendary American nature writer Edward Abbey in Desert Solitaire, back in 1968. Even in Gaia-centric British Columbia, our relationship with the natural world is a tangled, thorny mess — a description that also applies to Lewis’s narrative.

Less than halfway through her quest, Lewis pivots from list-ticking and attempts to find transcendence (that word, again) by simply smelling the flowers (more accurately, the moss) and meeting the forest on its terms. In an account that painstakingly records traditional place names and plant uses, she eventually sees the very notion of tree tracking as the twenty-first-century version of a colonial-style big game hunt. Relaxing, however, is not in Lewis’s nature. No forest bathing for her.

Reading Tracking Giants is a bit like scrolling through an Instagram feed, although instead of posting images, Lewis jumps around from one profundity to the next. The constant references to other people’s ideas become distracting. A meditation on deep time leads to quotes from Oliver Burkeman, Rebecca Solnit, and Cara Giaimo — and that’s just on one page. She painstakingly lists Indigenous uses for at least a half-dozen trees and plants, yet we don’t meet a single elder who might have shown her the forest from a non-Western perspective. This is what nature writing looks like in the age of social media.

Tracking Giants is more successful when it leaves the academics and New Yorker contributors behind — when its author gets muddy and mosquito-bitten in the field. Lewis starts promisingly, and I snorted with laughter at her opening line, “These fucking trees.” As someone who spent several hours bushwhacking through alder, blackberry, vine maple, and devil’s club during British Columbia’s infamous heat dome of 2021, trying to go from one distinct grove of big trees to another, I can relate. Once you’re off the beaten path, these forests are as unforgiving as they are inspiring.

Lewis craves connection with the rather motley group of (mostly) men who spend their free time studying satellite images, poring over historical accounts, and hammering rusty vehicles up dusty forest service roads, before bashing through the bush, analog and digital measuring instruments in hand, to triangulate the proper height, diameter, and crown spread of a potential new Champion. You can hear the screech of eagles, fondle the fronds of fireweed, and tightrope walk through fallen timber as Lewis finds her place alongside tree trackers like Mick Bailey, a peripatetic adventurer from Vancouver Island whose blog I’ve read for years. Some trackers can become quite proprietary in their quest; indeed, I appreciate the attitude of one who cuts off flagging tape and removes any physical clues that might reveal a tree’s exact location. Surprisingly, Lewis gives credit to foresters at Western Forest Products (yes, the logging company) for both identifying and protecting the few remaining stands of old-growth within its tenure.

As the owner of some frequently unreliable vehicles that have broken down on logging roads, I can also relate to Lewis’s christening her subcompact Toyota Yaris “Trouble.” While tree huggers might anthropomorphize Big Lonely Doug (a Douglas fir on Vancouver Island that even has its own biography), most hikers and climbers have owned at least one vehicle that seems to have a mind of its own.

Tracking Giants is a love letter to British Columbia’s big trees, but there’s surprisingly little mention of wood products. At one point, Lewis purchases a log cabin on Gabriola Island (not an option for the vast majority of millennials who work in the creative arts) and becomes conflicted about burning logs for heat. And, yes, her book is printed on FSC-certified paper (the Forest Stewardship Council label “means that materials used for the product have been responsibly sourced,” the copyright page helpfully points out). But in the time it took Lewis to write this thin volume, tens of thousands of trees were cut, milled, pulped, and transformed into the many other products we use every day. What does she make of that?

Tracking Giants has parallels with Bill Bryson’s A Walk in the Woods. As Lewis does eighty pages into her quest, the American humorist called it quits — in his case, on the Appalachian Trail — fairly early on. He never achieved the transcendence that woodsy philosophers like Emerson, Whitman, and Thoreau found in the nineteenth century. Bryson’s modern classic was, however, optioned by Hollywood and made into a buddy movie that was sort of a last hurrah for two aging Champions, Nick Nolte and Robert Redford. There are plenty of funny, self-deprecating scenes in Tracking Giants that might lend themselves to a similar send-up. Indeed, Netflix producers here in Hollywood North would do well to get their hands on Tracking Giants. This might be a case where the movie would be better than the book.

Steven Threndyle lives a short hike away from Vancouver’s North Shore mountains.