The year was 1972, the month was April, and I was in Oxford to attend a weekend symposium on leftist politics organized by a group of Canadian graduate students at the university. Having just crawled across the finish line of my own postgraduate degree, I was at the start of a summer-long hitchhike around Britain and in no mood to sit incarcerated in an overheated room while a dozen of my compatriots lectured one another about nationalizing the banks, banning nuclear weapons, and the perils of selling water to the Americans. The pros and cons of Manitoba’s NDP government, elected in 1969, were weighed with convincing authority by a doctoral candidate from Winnipeg who hadn’t been home in six years.

Long-winded intervention followed zealous discussion followed dry presentation while I waited to hear my friend Steven deliver his paper on the exploitative practices of a Canadian multinational in East Africa. My mind wandered out the window to the blue sky and the Constable clouds. William Walton was premiering his “Jubilate Deo” at Christ Church down the road. Thousands of gorgeous snake’s head fritillaries were blooming in the Water Meadow behind Magdalen College. A beautiful spring weekend was passing me by: there was a world to explore beyond this bastion of learning.

But fly our paths, our feverish contact fly!

For strong the infection of our mental strife,

Which, though it gives no bliss, yet spoils for rest;

And we should win thee from thy own fair life,

Like us distracted, and like us unblest.

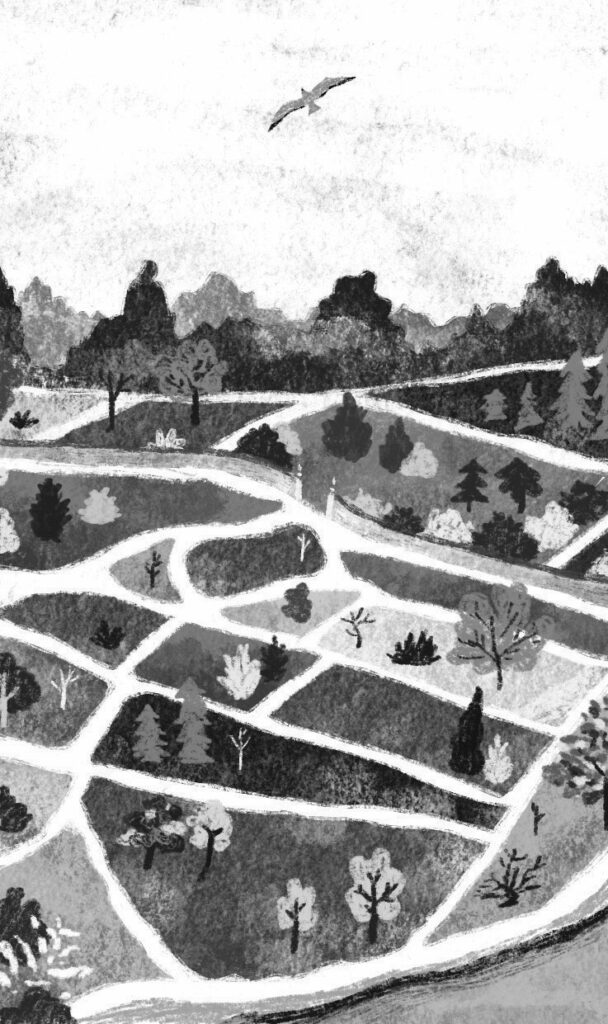

My immediate destination was the Botanic Garden, founded in 1621 on the site of a Jewish burial ground outside the walls of the medieval town by the River Cherwell. Known as the Physic Garden until 1840, it hadn’t been designed for beauty or for food but as “a place whereby learning, especially the Faculty of Medicine, might be improved.” Explorers and plant hunters had sent exotic species from around the globe for observation, classification, and cross-pollination there. Its four quadrants, laid out in the monastic tradition, were packed with thousands of herbs, trees, and flowers from which doctors, scientists, and apothecaries extracted medicinal potions and, who knows, perhaps recreational drugs as well.

Like a bird on the wind.

Nicole Iu

However serene, however interesting, the Botanic Garden gave me no respite that Sunday afternoon. On the contrary, it aggravated my feeling of entrapment. If gardens had begun as royal parks for the hunting of stags or private reserves for the contemplation of beauty, this one had taken the idea of enclosure to an extreme. The four-metre stone walls seemed to be imprisoning the natural world instead of protecting it. The plants resembled small, vulnerable creatures plucked from their native habitat and caged in captivity, compelled to stand erect in perfectly straight rows, condemned to any experiment or transmutation that might assist in the advancement of science. Their Latin names struck me as less the christening of a child than the branding of a slave, bestowed not as a celebration of their unique identity but as an act of domination and abstraction. As Jean-Jacques Rousseau observed on one of his walks in the countryside, “All the charming and gracious details of the structure of plants hold little interest for anyone whose sole aim is to pound them all up into a mortar, and it is no good seeking garlands for shepherdesses among the ingredients of an enema.”

It’s darkly appropriate, I thought, that this early manifestation of the Enlightenment had been built upon the graves of dead Jews, just as the great cities of the Americas had been built upon the bones of slaughtered nations. I perceived in a flash how we, the heirs of European civilization, have buried all evidence of pillage and blood in our own walled gardens of the mind. I was fed up with the tyranny of reason, the conceit of empiricism, and the tedium of scholarship. Walking along the linear paths that intersected the garden’s sections, so perfectly straight, so perfectly logical, I longed for the wild places from which these roses and chrysanthemums had originated and the dangerous journeys of the travellers who had gone in search of them.

I went to places no wilder than Cornwall, no more dangerous than Dartmoor, before circling back to Oxford a few weeks later. The intoxicating promise of an English spring had dissolved into torrential downpours and chilly winds. The newspapers were full of rail disruptions, a dockers’ strike, IRA killings, the bombing of Hanoi, and the one million unemployed. The faces on Cornmarket Street looked as grey as the buildings, and there was a grim, grumbling gloom in the pubs where, to paraphrase John Keats when he too was in his mid-twenties, men sat and heard each other groan, where youth grew pale and spectre-thin, where to think was to be full of sorrow and leaden‑eyed despairs.

Kathy was there by then, taking literature courses at Trinity. Never lovers, we’d been good friends at grad school, and after the weeks of solitary travel I took heightened pleasure in her company. One evening, after pub fare at the Turf, we went to see Éric Rohmer’s Le genou de Claire in the cinema up Walton Street. Jérôme, a handsome, middle-aged swain, returns one July to his childhood home on Lac d’Annecy. Soon to be married, he becomes obsessed with a young beauty named Claire — or, more particularly, with her knee — and sets out to make one final conquest, as much for her education (or so he deludes himself) as for his vanity.

For all its predatory overtones and intellectual pretentiousness, I found the film’s talk about love, lust, and the complicated relationships between men and women as sweet and light as a meringue — and so delightfully French. Why hadn’t Kathy and I talked at dinner, even pretentiously, of love, lust, and the complicated relationships between men and women? Why, in the darkness of the movie theatre, hadn’t I reached over to caress her knee? When we reached her boarding house, I gave her a goodnight peck on the cheek and walked alone through the warm, fragrant night to the lumpy sofa that Bob, a Balliol student I had met at the symposium, was allowing me to occupy in his sitting room on my way north to Scotland.

I fell asleep to images of the snow-capped peaks of the Haute-Savoie, the sunlight on the lake, the wildflowers in the meadows, the picnics in the verdant garden, the girls picking ripe cherries, the afternoons devoted to sensual pleasure, the hours spent in a fraught romance. And though I knew Rohmer’s world to be a work of imagination, a mechanical trick of light and sound, I wanted to believe that it really existed somewhere, exactly like that.

I was jolted from my sleep three hours later by an inspiration, like Keats’s nightingale, that left me fully awake and in a fever pitch of excitement. It was as though my subconscious had put together the pieces of a puzzle I had been toying with before going to bed. With a clarity as illuminating as the lamp I now turned on, I saw that tomorrow would be a completely new and empty day. Nothing compelled me to go north to Scotland. Nothing prevented me from fleeing dark, dreary, dank, depressed England. I could catch the morning train to London and get lickety-split to the wine, song, and sun of France. I was absolutely and existentially free.

O, for a draught of vintage! that hath been

Cool’d a long age in the deep-delved earth,

Tasting of Flora and the country green,

Dance, and Provençal song, and sunburnt mirth!

O for a beaker full of the warm South

Kathy, of all people, would know her Keats. I hastily pulled on my clothes and ran as though for my life through deserted streets in the middle of the night. Her boarding house was dark and locked. I crept like a prowler around to the back lane and lucked upon an old wooden ladder lying at the base of the high brick wall that was topped with sharp shards of glass set in cement. I climbed the ladder, stepped gingerly along the wall, and dropped down into the garden, where I tossed pebbles against Kathy’s second-floor window until she appeared, dishevelled, disoriented, and alarmed.

“Let me in,” I called with a stage whisper. “I’ve got something important to tell you.”

Moments later, I was in her room, delivering a rapid, exuberant, barely coherent explanation of why I thought she should drop everything and come away with me to France. She wasn’t angry, merely bewildered, and seemed to suspect, judging by her look of weary indulgence, that I had smoked a couple of joints and was now seized by a run-of-the-mill cosmic conviction that would be exposed in the light of morning as utter nonsense.

“You may be free, but I’m not,” Kathy said when she had heard enough. “I have classes tomorrow, my parents have paid for me to be here, and I don’t want to go with you to the South of France. I want to go back to sleep.”

The next day’s showers failed to dampen my enthusiasm. Nor did Bob’s wet-blanket reaction when I tried to explain my revelation over tea and toast. “Hegel says,” he replied, “we believe we’re free when we’re permitted to act arbitrarily, but in that very arbitrariness lies the fact that we are not free.”

I refused to be dissuaded. On the contrary, it then struck me that I didn’t have to go to France to put my freedom to the test. I could just as effectively, and more immediately, walk to the outskirts of town and surrender myself to chance.

I had done thousands of miles of hitchhiking by that point. I knew the fun and the fear of watching a car slow down and stop, of running to reach it before the driver changed his or her mind, of opening the door and getting in, of putting my life into the hands of a total stranger. But this would be different. Previously, I had always known where I was headed and seldom deviated from my determined destination. Now, however, I would go wherever I was taken, a bird on the wind, random, irrational, present, never knowing, like Wordsworth, what dwelling shall receive me or what clear stream shall lull me into rest, but with a heart — like his, I hoped — not scared at its own liberty.

I packed up my knapsack, hoisted it on my back, and bade farewell to Bob as he headed for a day in the Bodleian. I strode down St. Aldate’s in a light rain and crossed the Thames at Folly Bridge.

Ron Graham is an award-winning journalist and the author of The Last Act: Pierre Trudeau, the Gang of Eight, and the Fight for Canada.