The curator Sarah Milroy asks, “Was Kurelek celebrating the success of Jewish settlers in Canada or grieving their struggle to belong?” It’s an apt question, given William Kurelek’s bedevilled life. Born in 1927, to Ukrainian Orthodox parents on a grain farm north of Willingdon, Alberta, he was the eldest of seven children. He knew what it meant to be an outsider in a community dominated by Anglo-Saxon Protestants, particularly in and around Hamilton (where his family relocated in 1948) and Toronto (where he studied art at the Ontario College of Art). And he knew hardship first-hand: hardscrabble farm life, mockery at school for his ethnicity and language, and parental disapproval for being physically inept and a dreamer, prone to horrifying hallucinations.

His art was largely representational and narrative driven, though later came some very intense exceptions, such as Zaporozhian Cossacks (1952), The Tower of Babel (1954), Lord That I May See (1955), and Hailstorm in Alberta (1961). These were marked by such elements as dramatic or melodramatic arrangement, eerie religiosity, and ominous, misshapen, surrealist forms. Kurelek’s work was much influenced by Bruegel the Elder and Bosch and somewhat by Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo. Another palpable influence was the artist’s own mental illness, which was not cured by his conversion to Roman Catholicism in 1957.

Three years earlier — after he mutilated his face and arms and overdosed on sleeping pills in what he described as a “half-measure” attempt at suicide — Kurelek had submitted to electroconvulsive therapy for several months. This extreme brutality bled into some of his painting, especially in the series The Passion of Christ (1960–63), which depicted Jesus’s battered face and body in such an urgent manner that it deeply affected the artist Natalka Husar, who broke into tears upon discovering the work after she had moved to Canada from the United States. In an interview with Milroy (one of her book’s highlights), Husar explains, “It wasn’t just paint, or an illustration of a story we all know, but something that he couldn’t not paint — because he had to tell you this story. It was like he went somewhere, and he saw it. And he sent a picture back for you to see.”

It seems to articulate two visions of the immigrant experience at once: on the one hand, a sunny story of rejoicing brides, contented dairy farmers, cheerful children at their violin practice; and on the other hand, a darker story of abandoned farms, harassed street merchants, and forlorn new immigrants huddled on train platforms far from their homelands.

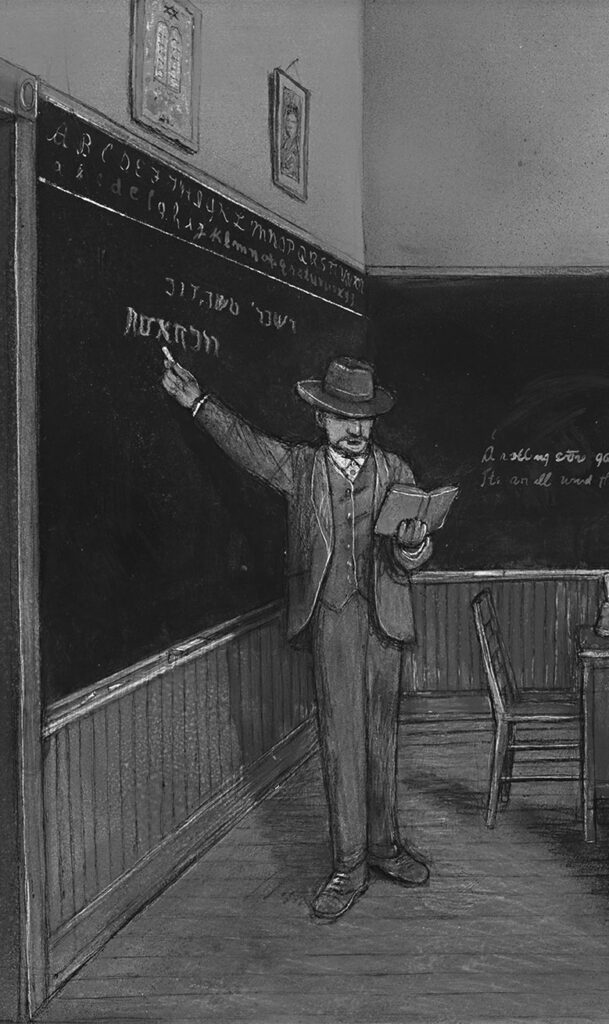

With gibberish on the chalkboard.

Detail of Jewish Separate School in Winnipeg; Wynick/Tuck Gallery; courtesy of McMichael Canadian Art Collection

In this book, which follows from a recently closed exhibition that Milroy curated at the McMichael Canadian Art Collection, in Kleinburg, Ontario, each work in the series appears first in full, then in details on the following spreads. Despite such high production quality, there is scant analysis of Kurelek’s actual technique.

In her introduction, Milroy describes the series as “a long-gestating act of personal atonement.” The Kureleks had initially supported Germany during the Second World War, because they had experienced vile racism and harassment by Canadians of British heritage. William did come to celebrate Canada’s multiculturalism, which he commemorated in paintings of various groups: Irish, Polish, Ukrainian, rural Québécois, and Indigenous communities, as well as pioneer women on the prairies and lumberjacks. Although Milroy includes some striking art — Immigrants Crossing the Atlantic (1966) and Gotta Get Home (1974) among them — she offers no critique. She ends by praising Kurelek for the “warmth” of his imagination and his “dream of a nation where all can belong,” thus conveniently dividing content from form.

Elsewhere in the book, the historian David S. Koffman argues that Kurelek painted the Jewish Life in Canada series not as if he were a Jew recouping cultural memories but as an act of “chesed, of loving-kindness for Av Isaacs, his Jewish friend, art dealer, supporter, and patron.” Koffman refers to Kurelek’s “naive painting style,” with its “almost idyllic vignettes” of domestic, cultural, and communal life “rendered in vibrant colours.” Recognizing that the paintings are “disproportionately skewed to the West,” Koffman lists “errors” regarding cultural practices: “a lighted menorah during a Pesach Seder in Doctor’s Family Celebrating Passover in Halifax” and “a shofar blower off to the side of the Yom Kippur service rather than front and centre on the bimah” in Yom Kippur. He also notes “gibberish Yiddish” on a classroom chalkboard in Jewish Separate School in Winnipeg.

The value of Koffman’s essay is more socio-historical than aesthetic. Similarly, the associate curator John Geoghegan seems to be carping on minor details. He stresses, for instance, that Kurelek elected to highlight generalized experiences rather than individual ones, sometimes obscuring aspects of his photographic sources, some of which are also included.

Not that Kurelek, who died in 1977 at age fifty, offered much explanation of his own technique. His annotations, many reprinted here, are lacklustre. They merely note what most of us can already see clearly. In Jewish Immigrants Arriving on the Prairies, an isolated woman stands in the foreground. In Jewish Home Life, Montreal, a mother prepares blintzes in the kitchen. In the adjoining dining room, her children study or practise the violin near various religious objects (a Hanukkah candelabra, a spice box, a mezuzah). And behind the closed glass doors of a small library, a group of men study the Torah.

In general, Kurelek is a simple documentarian in this series. His technique is plainly rudimentary in its delineation of scenes and figures — hardly better than a filmmaker’s storyboard. His remarks are more historical, social, and cultural than they are aesthetic, so even when he writes of using a photo of Jewish scholars from a Montreal Zionist fraternity, we can’t really discern clear features, other than frizzy or lank hair or beards. The first truly striking painting that transcends mere illustration is Bender Hamlet, the Farming Colony That Failed, where his washes achieve rhythm of colour and design. The panel’s frame consists of “black pen and ink drawings,” clipped from a woman’s old diary. “I want to convey the idea that these memories are like voices in the wind as it sighs through the thistles of the overgrown fields,” he explained poetically.

Like Georges Seurat, who framed his pointillist pictures with a pointillist border made up of complementary colours, but with a very different approach, Kurelek deployed colour and texture to create visual vibrations within the painting, setting up contrasts and harmonies with the subject’s colours.

Dejardin says “a Kurelek frame is never passive.” The one around Bender Hamlet, the Farming Colony That Failed, for example, uses a collage of texts: “some cut from books and articles, some typed and annotated — alongside drawn vignettes to surround the melancholy image of an abandoned farm falling into ruin under a pitiless sky, its infertile land strewn with a crop of stones.” The one around Jewish Baker’s Sabbath, Edmonton “takes two different yellows from the painting — the mother’s lemony skirt and the golden wood of the chairs — and turns up the volume with a high-gloss outer frame in bright yellow adjoining a lush piece of golden velvet.”

Through the pictured window frame is glimpsed a parallel reality that reads very much like a painting within the painting: the “factory floor” version of the small family artisan business in the foreground. The painted window frame is black, its inner edge grey, its glass panes (dividing the view into a triptych) outlined in white. Beyond is another window, also outlined in white and black, itself framed by the orange brickwork of the factory wall. Six outlining colours thus frame the view into the soulless factory production line. Meanwhile, the painting’s actual frame is a beauty: a black outer border, gorgeous crimson velvet facing within that, giving way to a narrower edging of hessian and then, astonishingly, an interior edge of the most vivid apple green, echoing the colour of the child’s dress being lovingly made to the right of the picture.

If only Jewish Life in Canada the book had more of such analysis! It might have kept Kurelek’s sincere good-heartedness and cultural diplomacy from overshadowing his art within its pages.

Keith Garebian has just published his eleventh poetry collection, Three-Way Renegade, as well as a memoir, Pieces of Myself.

Related Letters and Responses

Charles Heller Toronto