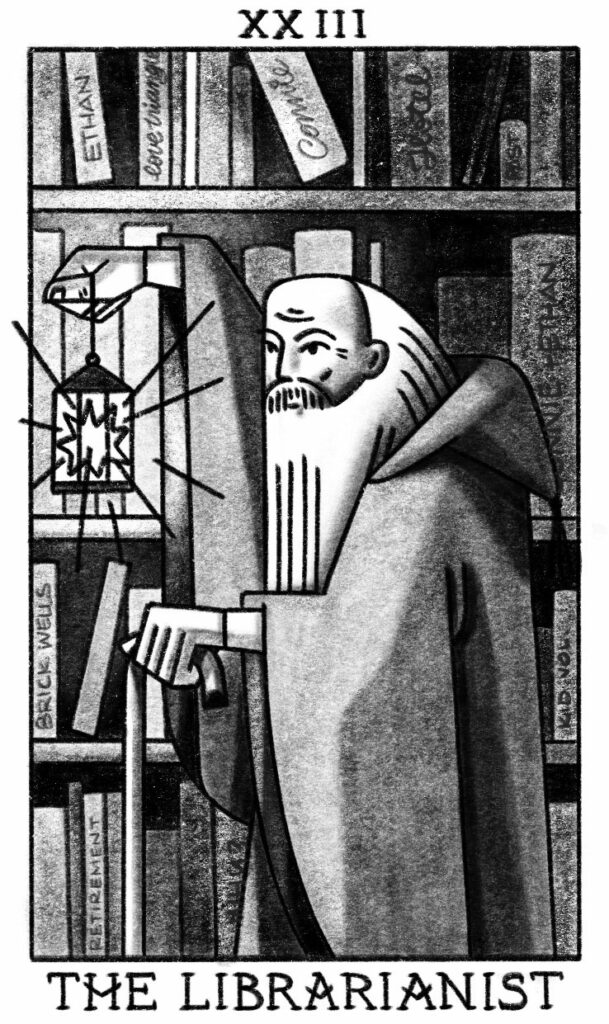

Patrick deWitt’s The Librarianist is, as the novel’s title suggests, about a librarian. As the obscure word “librarianist” further suggests, working in a library can be more than just a job. It can be something of an art, a calling.

This fun, messy novel — a major departure for deWitt in both setting and subject matter — works backwards in time, from the opening section of 2006, when the retired librarian Bob Comet has become something of a hermit, to the dissolution of his marriage years before, and into deepest childhood, all in a picaresque, scattershot attempt to answer a central question: “Why read at all? Why does anybody do it in the first place? Why do I?”

Although this is the third time deWitt has set a novel in the American West (both Ablutions and The Sisters Brothers take place in California), it is the first time we find ourselves in deWitt’s chosen home of Portland, Oregon. His love for the city is everywhere: how he names the quadrants, how he describes the architecture, how he imagines characters that could be extras on Portlandia. Comet lives in a mint-coloured house, which he inherited from his mother when he was twenty-three. Rope handrails run along the stairs and walls — a perfect deWittian detail (and remember what Chekhov says about rope handrails that appear in the first act).

It was a time of sterling certitude and grand plans, a kingdom coming into focus through the lens of a telescope, and they were riding in silence across the southwest quadrant of the city, holding hands and gazing out the window in the dreamy way lovers sometimes did and do.

An introspective protagonist from Portland.

Gwendoline Le Cunff

Unfortunately, trouble looms. Knowing Ethan’s penchant for sleeping with married women (with any woman, actually), Bob tries to keep his friend and his wife apart. But eventually the only two people in his life do meet and do fall in love, while Bob is only dimly aware of what’s transpiring.

Other sections of the book, like a long narrative about Bob’s experience as an eleven-year-old runaway at the Hotel Elba, on the Pacific coast, seem like distractions from the main narrative. The Victorian hotel, along with the larger-than-life travelling actors June and Ida, who take the young and bewildered boy under their wings, is better suited for a short story.

Bob, who we are reminded repeatedly is an introvert, who we are told “sometimes had the sense there was a well inside him, a long, bricked column of cold air with still water at the bottom,” nonetheless manages to get himself into all sorts of interesting relationships and whimsical situations. Even his decades of ordered aloneness end: in the novel’s present, he is warmly welcomed into the community of physically and emotionally damaged elderly residents at the Gambell-Reed Senior Center, including some unexpected people from his past.

As usual in a deWitt tale, Bob’s life is peopled with fascinating characters, all skilled at oratory and the roundabout quip: “I’m surprised to hear you care.” “I’m offended to hear you’re surprised.” “I’m apologetic at your being offended.” “I’m accepting of your apology.” There’s Ethan, of course. There’s Connie’s father, who made her wear a cape with a hood and spent his days riding Portland’s buses and proselytizing his own unique belief system: “Gender segregation. Sterilization of criminals. Public transportation. The death penalty. Disease. Gardening.” There’s Miss Ogilvie, Bob’s first boss after library school, whose “function, as she saw it, was to maintain the sacred nonnoise of the library environment” and who believed strongly in the use of corporal punishment. But mostly it is the Gambell-Reed residents who bounce off the page with their stories and complaints, especially Chip, the near-comatose woman whose attempt at escaping the centre brings Bob there in the first place.

All his life he had believed the real world was the world of books; it was here that mankind’s finest inclinations were represented. And this must have been true at some point in history, but now he understood the species had devolved and that this shrill, base, banal potpourri of humanity’s worst and weakest and laziest desires and behaviors was the document of the time.

That’s incisive enough commentary for TV, but where’s the similar incisiveness for literature?

It’s always interesting to consider what makes an author Canadian. While deWitt was born on Vancouver Island, he has spent most of his life in the United States, where he holds citizenship. He has never written about anything remotely Canadian. Yet we hang on to him as if he were the child of Margaret Atwood or Stephen Leacock. Americans claim him, too: Slate recently called him our century’s Mark Twain.

DeWitt’s most successful book to date, The Sisters Brothers, won or was nominated for several major Canadian literary awards, as well as the Booker, which, at the time, was not open to American writers. But, really, what does it mean to peg a novelist to the country where he was born? Isn’t it just as true to say deWitt is a Portland writer? A writer of the American West? A writer of sharp sentences and oddball individuals? In the end, it matters less where an author is from and more whether his books are any good. So, for those asking: If you’re a diehard deWitt fan, you’ll most likely dig The Librarianist. If, like Bob Comet, you’re simply a voracious reader of fiction, it’s anybody’s guess.

Aaron Kreuter is the author of Shifting Baseline Syndrome, which was shortlisted for the Governor General’s Award for Poetry in 2022.