Stolen gear, severed traplines, blocked boats, and a ransacked lobster plant set ablaze. It all unfolded on the shores of St. Marys Bay, in southwestern Nova Scotia, in the fall of 2020. The conflict boiled over when the local Mi’kmaw community, Sipekne’katik First Nation, angered a throng of non-Indigenous fishers by implementing its treaty right to operate a lobster fishery outside of the federally regulated season. Contested Waters reads as a time capsule of the ensuing dispute, while exploring its historical roots, the need for reconciliation in commercial fisheries, and possible flashpoints ahead. Edited by Fred Wien, an emeritus professor at Dalhousie University and a former staff member of the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples, and Rick Williams, research director for the Canadian Council of Fish Harvesters, this valuable book assembles more than two dozen contributions from Mi’kmaw and non-Indigenous leaders, academic and legal experts, and industry executives.

The compilation begins with a retrospective of Indigenous commercial fisheries since a landmark Supreme Court of Canada case in 1999. The two decisions in that case stemmed from the prosecution of Donald Marshall Jr., a member of the Membertou First Nation, who had caught and sold eel without a federal licence. The court ultimately overturned Marshall’s convictions, affirming the fishing rights that the eighteenth-century Peace and Friendship Treaties guaranteed to Indigenous peoples, specifically Mi’kmaw, Wolastoqey, and Peskotomuhkati communities in the Maritimes and the Gaspé region of Quebec.

Yet twenty years after the Marshall rulings, confusion still abounds. Wien and Williams argue that they “left critical decisions, including the appropriate share of the total commercial fishery and the meaning of ‘moderate livelihood,’ to be worked out.” Through authored chapters, transcribed interviews, and reprinted press releases, Contested Waters details divergent interpretations of what the court’s “moderate livelihood” phrase means today — and what a continued lack of clarity means for Canadians in the future.

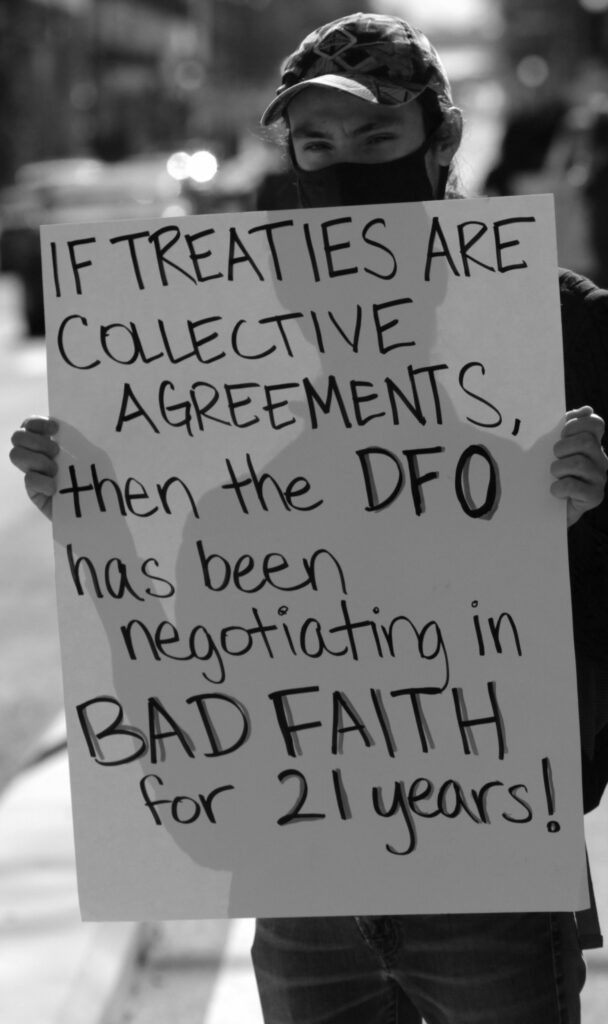

Since the turn of this century, Indigenous communities have successfully built a self-regulated “communal-commercial fishery,” which has resulted in jobs and revenues that benefit both individuals and bands. At the same time, commercial-sector leaders and Fisheries and Oceans Canada have argued that the federally run fishery is enough to fulfill the moderate livelihood right. “Until recently,” Williams writes, “DFO did not seem to have envisioned the creation of a distinct moderate livelihood fishing sector to provide opportunities for many more First Nations community members to catch and sell modest quantities of fish.”

The conflict came to a head in 2020.

Lee Brown; The Canadian Press Images

In September 2020, the Assembly of Nova Scotia Mi’kmaw Chiefs —“the highest level of decision making in the Rights Implementation and Consultation process” for the Mi’kmaq of Nova Scotia — released a public statement: “Despite our rights being affirmed by the highest courts in the country, exercising these rights continues to bring frustrations, conflict, and hardships to our people.” As Wien and Williams point out, however, the hardships long predated the specific dispute that was in the news. From early European settlers pushing Indigenous communities away from seasonal settlements on waters and seaways to more contemporary Canadian examples fuelled by the Indian Act, a methodical exclusion has progressively restricted fishing access. “The simple fact that at the close of the twentieth century coastal First Nations had only a tiny share of the huge commercial fishery in Atlantic waters is stark proof of a history of systematic racism and exclusion.”

When Sipekne’katik First Nation issued lobster licences to community members in the fall of 2020, it was working toward a self-governed commercial fisheries management model — what the assembly calls a “Netukulimk Livelihood” plan. The chiefs’ use of the word “Netukulimk”— which speaks to “a respectful and reciprocal relationship” with nature — emphasizes the need to protect the fisheries for future generations. “Accessing resources should not be about limiting, it should be framed as what we are doing to provide for future generations,” the Mi’kmaw elder Albert Marshall explains in an interview with Nadine Lefort of the Unama’ki Institute of Natural Resources. “The concept of Netukulimk implies our inherent responsibilities in continuing a relationship with species and the entirety of an ecosystem.”

Recent revisions to the Fisheries Act mean that Ottawa is legally obligated to rebuild depleted stocks and incorporate the unique knowledge systems held by Indigenous people into management planning. If such a vision is ever to come to fruition, it requires a shared sense of understanding and respect. Underlying the 2020 lobster dispute, Allister Surette, a former MLA and president of Université Sainte-Anne, says in an interview with Wien and Williams, is “a long-standing lack of trust between fish harvesters and DFO, and between First Nations leaders and government.” And this, he continues, “makes progress difficult.”

Surette, who in October 2020 was named a “federal special representative to act as a neutral third party,” believes discussions about the fishery can advance only if affected parties get back to basics: “We are neighbours in our communities, we know one another from going to the same schools, same workplaces, and playing sports. I believe that the majority of people in all communities are reasonable and want to see things work out peacefully and fairly.”

Across Canada — which has the longest coastline of any country — fishing boats in harbours and fish plants at shorelines are the lifeblood of many communities. That’s particularly true in this part of Nova Scotia, home to the richest lobster fishing areas in Canada. Here, the crustacean represents more than traditional food and more than a livelihood. Perhaps especially for Indigenous communities, it is tantamount to identity and culture. Contested Waters thoughtfully explains to readers what’s at stake in finding a way forward in this ongoing dispute and others like it. “If ever there has been a time when it is both necessary and feasible to find a constructive path to reconciliation in Atlantic fisheries,” Wien and Williams write, “it may be now.”

Jenn Thornhill Verma is a journalist covering fisheries, oceans, and climate change.