On the surface, the 2021 federal election changed almost nothing. Going into that contest, the Liberals and Conservatives held 155 and 119 seats, respectively. Coming out, they had 160 and 119. Justin Trudeau started the campaign with a minority government, and he finished with a minority government. Each party’s share of the popular vote barely budged from its numbers in the previous election. A pandemic had upended every facet of Canadian life, but federal politics ended up right where it had been. Plus ça change, plus c’est la même chose.

As it turns out, though, 2021 did break new ground. Shortly after election night, a team of researchers reported that the split between urban and rural Canada was, at least by one measure, larger than ever before. Using their own yardstick of “urbanity”— a metric that includes more than simple population density — David Armstrong and Zack Taylor, from Western University, and Jack Lucas, from the University of Calgary, showed that the Liberal vote advantage was now stronger than it had ever been in urban ridings and that of the Conservative vote was stronger than it had ever been in rural ridings.

If the gap between urban and rural ridings had never been wider, the divide was not new. The beginnings of the great divergence, the researchers wrote, could be traced to the 1960s, when John Diefenbaker and Lester B. Pearson effectively redrew the electoral map: the split in 2021 was merely the continuation of a long-term trend. Or, as John Ibbitson writes in The Duel: Diefenbaker, Pearson and the Making of Modern Canada, “The elections of 1963 and ’65 created the social and political divides that define Canada today.”

The electoral split between urban and rural was not the only reason to turn one’s mind to the 1960s in the aftermath of the 2021 election. While Erin O’Toole could claim a kind of victory in having held the Liberals to a minority, he had a flimsy grasp on the Conservatives — the result of his own ham-fisted attempt to bridge the divide between the party’s base and the more moderate voters it seemingly needed to persuade if it ever wanted to form government again. The arrival of the self-styled Freedom Convoy in Ottawa finally sent O’Toole’s balancing act crashing down — and ushered in the arrival of the uncompromising Pierre Poilievre.

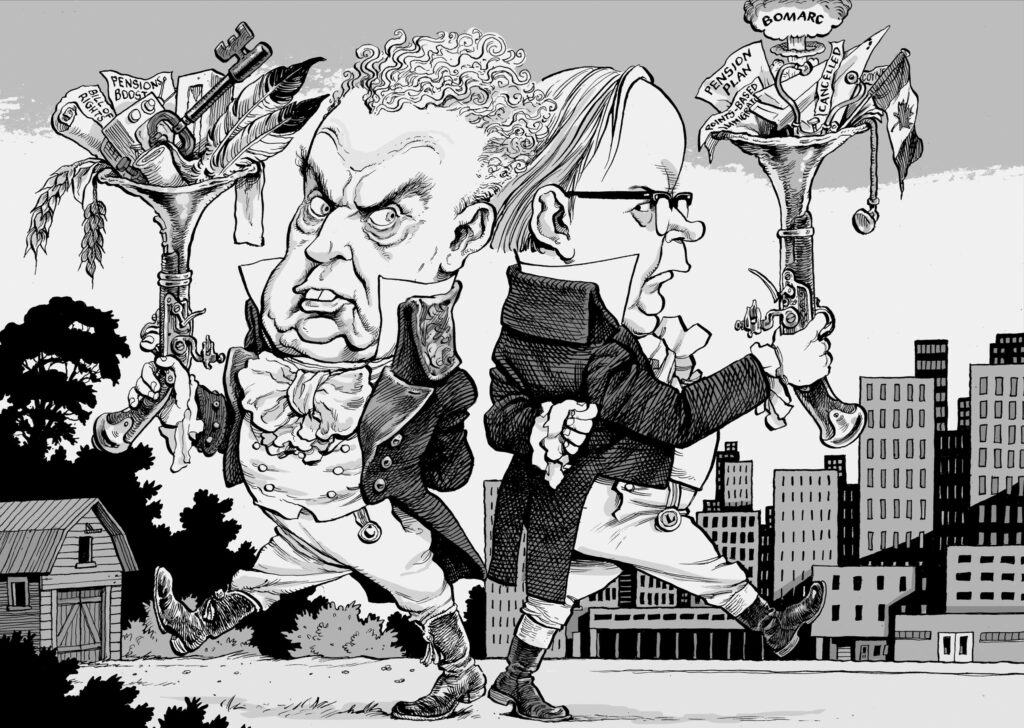

The Chief and Mike faced off with their distinctive ammunition in four federal elections.

David Parkins

Whatever else Poilievre ends up accomplishing, he is already Canada’s most populist Conservative leader since Diefenbaker. And it just so happens that Poilievre is attempting to defeat and replace, in Trudeau, the most activist prime minister since Pearson. All of which makes this moment a particularly good one to revisit the two men who presided over this country from 1957 to 1968.

Ibbitson’s dual biography follows John C. Courtney’s equally elucidating Revival and Change, published in late 2022 (and reviewed in the April 2023 issue of this magazine by Murray Campbell). Whereas Courtney focuses almost exclusively on the 1957 and 1958 campaigns, Ibbitson covers much of what the thirteenth and fourteenth prime ministers experienced before and after. He neatly and eloquently weaves together the stories of Diefenbaker (“a solitary boy who became a solitary man”) and Pearson (“people of power and influence liked him and were impressed by him and enjoyed his company”) to explain how two very different individuals eventually came to the same place at the same time — as well as what they did once they got there.

The portrait that Ibbitson paints is most kind to Diefenbaker. If schoolchildren know the man from Prince Albert for anything, it is probably as Canada’s jowliest prime minister. Or perhaps for the Diefenbunker, the expansive bomb shelter in Carp, Ontario, that is now a tourist attraction. His win in 1958 — the Progressive Conservatives took 208 of 265 seats — remains the most smashing victory in Canadian history, but he was out of office five years later. When academics were last asked to rank prime ministers — in 2016 — Diefenbaker finished twelfth, two spots behind Justin Trudeau, who had been in office for less than a year.

Ibbitson is clearly, and candidly, sympathetic to the Chief. He posits early on that Diefenbaker “has been unfairly treated by history,” and he admits in his epilogue that “one purpose of this book has been to attempt to dispel the false narrative that the two Pearson governments accomplished much while the three Diefenbaker governments accomplished little.” Rescuing political history from the muck of scandal and intrigue — while still making some room for the scandal and intrigue, if only because playing in the mud is a lot of fun — is very worthy work.

Although Pearson was covered in his own share of muck by the time he left office — and was quickly swept aside amid the national swoon for Pierre Trudeau — history has been very generous to him. Indeed, his accomplishments in office are well known: medicare, the Canada Pension Plan, a points-based immigration system, a new flag. In that same survey of experts, Pearson was ranked the fifth-best prime minister, even though he spent just less than five years in office (by longevity, Pearson ranks thirteenth). For sheer likeability, Pearson might rank even higher.

If Diefenbaker is due for another consideration, it is in no small part because his political ascent seems to echo in the present: he was a firebrand populist who used an emerging medium (television) and new marketing techniques to capture the support of a great swath of the nation. “In Diefenbaker’s passion is incorporated all the grievances of his audience,” Dalton Camp, the strategist and commentator, wrote after watching Diefenbaker address a crowd during the 1957 campaign. Six years later, Ibbitson points out, the flailing prime minister spent a losing campaign “attacking Pearson, the press, the backroom boys, Bay Street, and socialism.”

In between the grievances and resentment, Diefenbaker built a formidable record: prison reform, enfranchising First Nations, a bill of rights, a boost to pensions, universal hospital care, major infrastructure and regional development projects, an end to race-based immigration, wheat sales to China, the first female cabinet minister, the first Indigenous senator, and royal commissions on taxation and health services. By 1963, the Conservatives were nonetheless carrying the baggage of various scandals and spectacles: the cancellation of the Avro Arrow, the Bomarc missile crisis, the Coyne affair. The Liberals were reinvigorated, and Diefenbaker was soon sent back to the opposition benches that suited him so well.

Still, Ibbitson argues, even as Diefenbaker was ranting against “socialism” and Pearson was promising bold change, the Conservative and Liberal platforms in 1963 “complemented each other.” On support for cities, health care, immigration, and federal-provincial relations, the Liberals were proposing to build on initiatives taken by Conservatives — just as Diefenbaker’s government had expanded on what Louis St‑Laurent’s government did. Ibbitson quotes Diefenbaker’s belief, written into the Conservative platform, that “government must assume a full measure of responsibility for those social requirements which, by their very nature, cannot be assumed by business and the business community.”

The urban-rural divide that began to take shape in 1963 — Ibbitson notes that the riding of Toronto Centre flipped from Conservative to Liberal in that election, and sixty years later it’s hard to imagine it ever going blue again — is hardly unique to Canada. And even if their electoral choices are different, it’s not yet obvious that rural and urban Canadians are necessarily growing further apart or becoming antagonistic. While we have always had to worry about our differences, the new era of populist politics has loudly demonstrated — in the United States and elsewhere — how destructive such divisions can be.

Populism is an inherently divisive strain of politics. It asks voters to believe that any given debate or issue can be boiled down to a contest between “the people” and “the elites.” It derives its power not simply from identifying problems to solve, but from identifying someone to blame. It requires villains. For all those reasons, it can have a very potent appeal. But what modern populism has yet to show is that it can be used to govern constructively. The point of politics in a democracy is not merely to stoke resentment or give voice to grievances, but to address and resolve real frustrations, problems, and injustices.

Diefenbaker might be better known for his jowls and the indignation those jowls helped to convey. But his record suggests he found a way to build, not just blame.

Aaron Wherry has covered Parliament Hill since 2007.