To his many fans, Captain Jean-Luc Picard of the starship Enterprise embodies the best qualities of twentieth-century humanity projected onto a twenty-fourth-century future. As our representative to other species in the galaxy, he is moral, dignified, compassionate, intelligent, and cultured, all of which is symbolized by his beverage of choice: “Tea. Earl Grey. Hot.” Although the captain grew up in a French vineyard, in the Star Trek universe only the bellicose Klingons drain vat after vat of blood wine.

Picard’s favourite tea, and mine, is named after Charles Grey, the British prime minister from November 1830 to July 1834. A popular legend holds that Earl Grey tea was created by a Chinese official whose son had been saved from drowning by one of the peer’s men, but since Grey never set foot in China, this is unlikely. An alternative and more probable origin story is that bergamot oil was added to black tea to mask the taste of lime in the water at Howick Hall, the Grey estate in Northumberland.

As a lifelong fan of the North American bergamot flower — also known as bee balm, monarda, and Oswego tea, and beloved of ruby-throated hummingbirds and other pollinators — I was disappointed to learn that the bergamot that flavours my beverage of choice is Citrus bergamia, a small, winter-blossoming tree native to southern Italy. The tree’s fruit is consumed in few places other than Mauritius, though it is used to make marmalade in Turkey. Elsewhere, it is harvested mainly to produce essential oil. A hundred bergamot oranges yield about eighty-five grams of it. For comparison, about 242,000 rose petals are required to distill approximately five grams of rose oil.

Helen Dunmore, the novelist and my dear friend, always wore Chanel No. 5, for which attar of roses is an essential ingredient. She also drank as much tea as I do —“Fancy a cup of tea?” being her immediate query upon returning from any outing, whether a two-hour ramble through the winding lanes of St. Ives or a brief trip to Tesco to pick up ingredients for dinner. While living in England, I discovered how many of my enthusiasms — gardening, dogs, hiking, cryptic crosswords, birdwatching, second-hand bookshops — were shared there. Perhaps some preoccupations were transmitted through the innumerable cups of tea I have consumed in my lifetime, transforming that which flows through my veins into something dark, aromatic, and prone to bad puns.

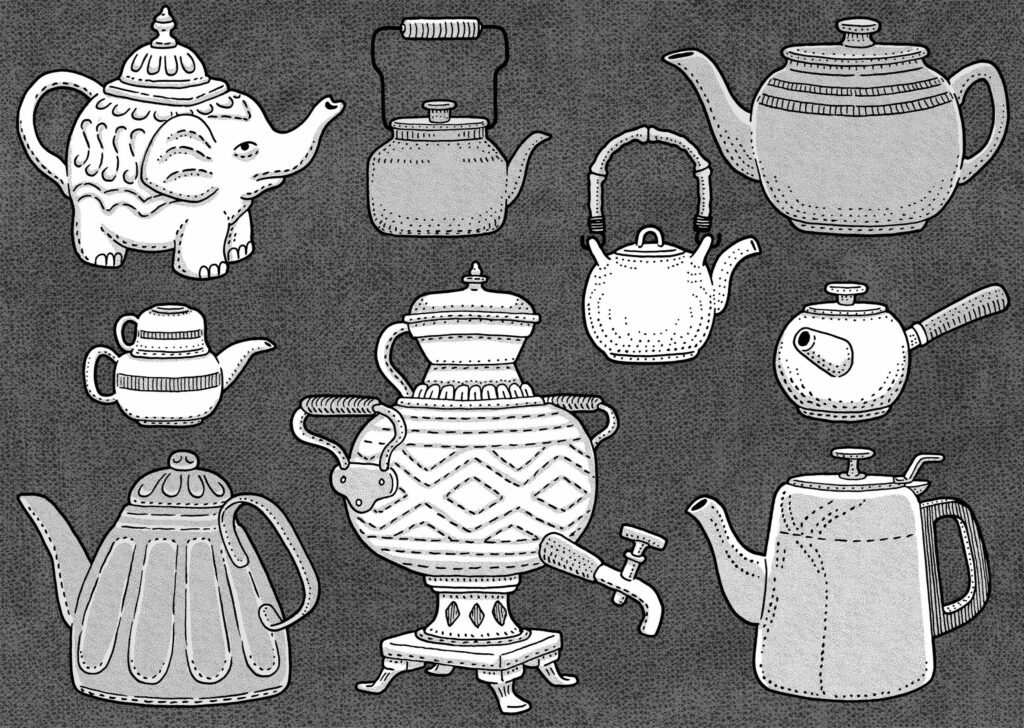

A teapot for every taste.

Tom Chitty

The British are not, in fact, the planet’s greatest tea drinkers; Turks hold that distinction. Actually, tea is the most popular beverage in the world after water, which is fundamentally what tea is: flavoured water. Global consumption of tea equals that of all other drinks, including coffee, alcohol, and soda pop, combined. And all tea derives from the same plant: Camellia sinensis, an evergreen shrub native to East Asia. The differences between the four main types of tea — white, green, oolong, and black — depend upon the degree of oxidation allowed in the leaves before they are dried and heat-treated.

Some say that tea drinking was introduced by the Chinese emperor Shen Nung in 2737 BCE, when a single leaf fell into a pot of water his servant was boiling and he decided to taste the infusion. The oldest tea leaves archeologists have unearthed date from the Han Dynasty, early second century BCE, so the association of tea with China is certain even if the precise date of its discovery is not. Saying that one refused to do something “for all the tea in China” was a common figure of speech when I was growing up. A rhetorical cognate is “What does that have to do with the price of tea in China?”— suggesting that a previous comment is irrelevant. Most other idioms involving tea emphasize its consumption, such as saying that something is “just one’s cup of tea” (or the opposite). Tea is also yoked with sympathy: you’re basically bound to offer it to someone in distress. Tea and Sympathy is the title of a 1953 play by Robert Anderson, about a teenaged boy accused of effeminacy for preferring the arts to sports. Although it had been a success on Broadway, the 1956 film version was able to satisfy the censors only by suppressing all suggestions of homosexuality. Instead, the adaptation implied that the emotional support of the housemaster’s wife (played by Deborah Kerr) culminated in adultery and that the student (played by John Kerr, no relation) eventually got married — things that this character, as originally conceived, would not have done “for all the tea in China.”

Chemists might describe tea as both a solution and a suspension. The water-soluble compounds extracted from tea leaves are held in solution, while the leaves themselves are only suspended. I can testify that in my personal life, tea is the solution to almost any problem, holding it in suspense while I take a break. Drinking a cuppa is the equivalent of a quick yoga session when I don’t have time or space to unroll my mat and start tallying breaths. Until recently, I used to drink a huge mug of milky tea before bed, but, alas, my aging body can no longer tolerate caffeine after 3:00 pm, so I now unwind with a tisane. My favourite is the Bengal Spice blend made by Celestial Seasonings. For once, a product’s advertisement is accurate: “Brimming with cinnamon, ginger, cardamom and cloves, this adventurous blend is our caffeine-free interpretation of chai, the piquant Indian brew traditionally made with black tea. Try it with milk and sugar for a true chai experience.”

Although it may surprise some, Indian chai is served with milk and sugar, as I discovered on a 1976 trip to study yoga at the Iyengar ashram. The English habit was transferred to folks on the subcontinent by their occupiers, and it distinguishes them from most other Asians. In fact, tea drinking was introduced to India by the British when they started cultivating Camellia sinensis there to break the Chinese monopoly on its production. Eventually an indigenous variety of tea was discovered in the northeastern region of Assam, and the colonial government offered free land to any European who agreed to cultivate tea for export. This may explain why the most famous Assam tea is called Irish Breakfast instead of Bharatiya Naashta.

During my sojourn, I made the requisite pilgrimage to Agra to visit the Taj Mahal. The temperature hovered around 40 degrees with 100 percent humidity, and my increasingly flexible but still Canadian body became a permeable membrane as I watched sweat bead on my arms after each sip of chai. It may seem counterintuitive to ingest a steaming potion in such sweltering conditions, but locals believe that this is the best way to cool down. Indeed, a 2012 study at the University of Ottawa confirmed what folk wisdom has always maintained: hot beverages stimulate the production of perspiration, which has a cooling effect on your body.

On a journey from Mumbai to Kolkata, I bought chai in little unglazed clay cups from vendors who ran beside the train at each station and passed them carefully through the window. These vessels, designed to be disposable, shattered in a satisfying way on the tracks as we trundled along. They also imparted an earthy but not unpleasant taste to the tea, which I thought at first I was imagining but turned out to be an accepted and cherished feature. Sadly, the traditional kulhar, in use for 5,000 years, has since been replaced by a plastic version, cheaper and lighter for vendors to carry but not biodegradable. In 2004, Indian Railways attempted to revive production of the containers for environmental reasons but got snarled in controversy over how much land was required to produce the clay, how much the potters would be paid, and how long the cups would take to break down in the soil. The debate is still ongoing and unresolved: a literal tempest in a teapot.

I myself have owned a wide variety of teapots, including the obligatory English Brown Betty, two different Japanese kyusu (one an ushirode kyusu or “back-handled” teapot, and the other a dobin kyusu or “top-handled” teapot), and even a whimsical little single-serving vessel with a matching cup perched upon it like a hat. I had schlepped the beautiful brass samovar from Morocco to England, along with its etched ruby glasses in brass holders. When the container holding all my earthly goods was smashed and its contents flooded with sea water on the deck of the cargo ship bearing them home to Canada, that samovar and my beloved purple bicycle — a ten-speed Raleigh purchased for a cycling adventure through the Black Mountains of Wales — were the only objects to survive.

Wondering if some meaning could be derived from the conjunction of those two possessions, I looked online for their symbolism. Apparently, a young girl “dreaming of a shiny clean samovar with hot tea inside is a sign of a good marriage with an agreeable man who would change her life for the better.” Well, I was running away from my English boyfriend, having decided life would be better without him. The bike imagery is also apt, since “a bicycle symbolizes the moving circle of life.” In my memories of India, chai wallahs ride bicycles with plastic samovars strapped to their backs. Although when I look for such images online, all I see is blokes hoisting battered metal tins. So maybe I dreamed that as well.

Tasseomancy is the art of divination by tea leaves. Reading Tea Leaves, written by “A Highland Seer” in 1881, is the oldest English book on the subject and provides an alphabetical list of the symbols to be discerned, as well as instructions for the practice. First, one must brew loose tea without adding milk or sugar. The person seeking answers (the querent) must sip the beverage while formulating a very specific question in their mind. Once there is only about a tablespoon of liquid left, they have to hold the cup in their left hand and swirl it three times, from left to right, before turning the cup upside down over a saucer. After a minute, they rotate the cup three times, before turning it right side up with the handle pointing south. The leaves remaining inside will reveal the answer to their question. The handle signifies the home, so any leaves scattered near it relate to immediate events, people, and issues. Leaves opposite the handle symbolize the outside world. The rim of the cup stands for the present, the sides represent the near future, and the bottom points to the distant future.

I cannot find a samovar among the book’s list of symbols, but a teapot represents knowledge hidden in the subconscious that the querent must access to solve current (top of the cup) or future (middle of the cup) problems. If the teapot shape sits at the bottom of the cup, it is seen as a warning not to rely on other people for advice. Of course, if I discerned a teapot among the leaves, I would conclude the obvious: that I needed another cup.

Susan Glickman will publish her eighth book of poetry, Cathedral/Grove, in September.

Related Letters and Responses

Jean O’Grady Toronto