In 1829, the fur-trading ship Volunteer sailed down the east coast of Haida Gwaii, then known to the wider world as the Queen Charlotte Islands, passing the village of Skidegate. Travelling with the traders was the missionary Jonathan S. Green, the first outsider to record his impressions of its cedar plank houses and totem poles. “To me the prospect was most enchanting, and, more than any thing I had seen, reminded me of a civilized country,” the reverend wrote. “The houses, of which there are thirty or forty, appeared tolerably good, and before the door of many of them stood a large mast carved in the form of the human countenance, of the dog, wolf, etc., neatly painted.”

Green was properly impressed. Yet his note encapsulates a tension that’s common in the observations of visitors who made their way to the coast of British Columbia and Alaska in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. Hesitant to acknowledge anything that rises quite to the level of “a civilized country,” he still finds the material culture before his eyes “enchanting.” The same conflicted response is seen in the first written European descriptions of Haida art, found in the journals of officers aboard the Solide, a French three-master that anchored off Haida Gwaii in 1791. To the ship’s surgeon, an intricately carved and painted house screen seen during a shore excursion initially appeared “to resemble nothing,” but, as the good doctor looked more closely, he had to admit it was executed with “sufficient intelligence to afford at a distance an agreeable object.”

The early interlopers who struggled to grasp what was before their eyes could scarcely have imagined the outsized place Haida design, especially totem poles and masks, would come to occupy around the world in major museums, private collections, and even the popular imagination. For many Canadians, the renaissance of Haida and other Pacific Northwest traditions in contemporary art since the 1970s now represents an unofficial national style, rivalling Group of Seven landscapes and Inuit sculpture and printmaking. (To the First Nations themselves, of course, their art means much more than a way to elevate an airport concourse or a corporate boardroom.) A crucial early chapter in how Haida creativity achieved such stature is expertly told in Skidegate House Models: From Haida Gwaii to the Chicago World’s Fair and Beyond by Robin K. Wright, a professor and curator emerita at the University of Washington in Seattle.

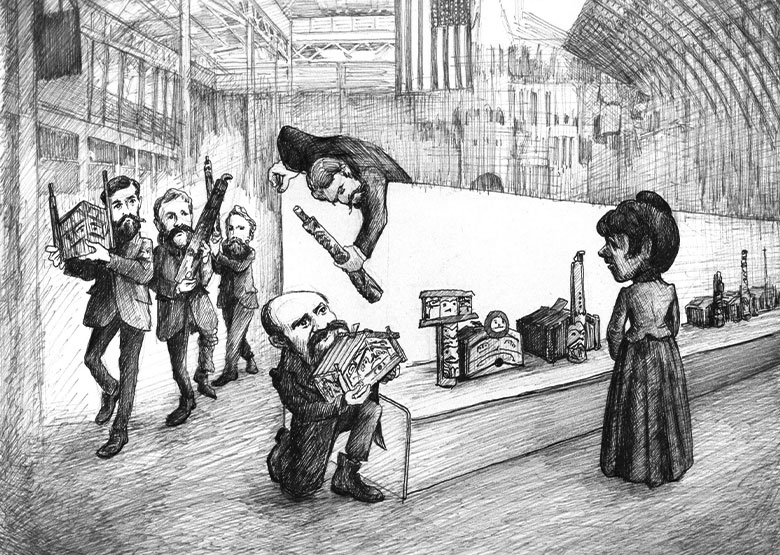

Carving out somewhat qualified space at the Chicago World’s Fair.

Silas Kaufman

The notion that a world’s fair should showcase Indigenous cultures was established before Chicago hosted the stupendous World’s Columbian Exposition in 1893. For Philadelphia’s fair in 1876, the Smithsonian Institution assembled exhibits meant to tell the story of the American Indian. In Paris in 1889, faux villages from the French colonies were set up. Chicago’s impresarios turned to Fredric Ward Putnam, an eminent Harvard anthropologist, to oversee its ethnology and archeology displays. As his right hand, Putnam picked Franz Boas, a young German American scholar who would become a foundational figure in modern anthropology.

The fair was meant to commemorate the four hundredth anniversary of Columbus’s famous 1492 voyage, and Putnam and Boas aspired to represent “on a grand scale” the peoples living in North America when Europeans began to wade ashore. The dark irony wasn’t lost on Indigenous leaders. Simon Pokagon, a Potawatomi activist, wrote that the fair amounted to celebrating “our own funeral, the discovery of America.” Pokagon’s scathing booklet The Red Man’s Rebuke was widely discussed at the time. Of course, the show went on. It featured the original Ferris Wheel, belly dancers, a Bedouin camp, Chinese theatre, a German beer hall. Throngs marvelled at the gimcrack neoclassical architecture of the famous White City.

But Putnam and Boas weren’t Barnum and Bailey. “Putnam had not planned for the WCE exhibits to be racist,” Wright explains. “Rather, he intended ‘the presentation of native life [to] be in every way satisfactory and creditable to the native peoples, and no exhibition of a degrading or derogatory character will be permitted.’ ” Still, nobody thought to ask Skidegate residents to be on hand to explain the artifacts and artwork assembled. “Nowhere at the WCE were the voices of the Haida heard, except as they were imbedded in the carvings themselves.”

Wright became fascinated by a carved model of Skidegate showcased in Chicago when she was researching Northern Haida Master Carvers, her landmark 2001 book, which is admired equally by scholars and by Haida artists who rely on it as a resource. More than a consummate connoisseur of Haida design motifs, Wright is also a tireless genealogical and archival researcher. Her opus corrected past misattributions and affixed the names of individual artists to previously anonymous nineteenth-century masterpieces.

In her latest book, she pieces together the tale of how the display came to be planned for the world’s fair, before turning to the Skidegate models themselves. Boas set the project in motion in 1892, hiring a dubious character named James Deans, a Scottish immigrant living in Victoria, to oversee the commissioning. The idea was to show Skidegate as it had been in 1864. Why that particular year was chosen isn’t clear, but Boas seemed to want to capture the village in a pristine state — still the beguiling sight described by Green decades earlier. Those days, tragically, were past. When Deans arrived in Skidegate to hire carvers for the Chicago job, only three of the traditional cedar plank houses were still standing, along with just a few of the archetypal poles.

It would be difficult to overstate the decimation the Pacific Northwest had endured by then. The Haida population plummeted from perhaps 10,000 in the early nineteenth century to less than 1,000 by the dawn of the twentieth century. Several smallpox epidemics had ripped through the region. Skidegate was home to 738 in the early 1830s but only about a hundred by the early 1880s. Missionaries and government agents did their worst to deny the survivors the solaces of carving, dancing, and potlatch ceremonies.

Deans nonetheless found a squad of artists ready to fulfill Boas’s vision. In all, seventeen worked on the models, often basing them on houses in which they had once lived. (The dimensions varied somewhat, but John Robson and David Skilduunaas’s Grizzly Bear House, for example, was ninety-eight centimetres wide and deep and fifty-three centimetres tall, with a ninety-three-centimetre pole out front.) The carvers largely ignored the assignment to show the village as it had been in 1864. Instead, they represented numerous structures erected somewhat later, when Haida from elsewhere along the coast migrated to Skidegate after sickness devastated their home communities. The carvers also decided against making strictly accurate copies in many cases. Comparing the carvings with early photographs of Skidegate (taken by pioneering photographers whose stories fill their own fascinating chapter in the book), Wright is able to itemize what were clearly intentional discrepancies between the replicas and the originals.

Wright’s survey of what she learned about the twenty-nine house models and the pole models that stood by them, along with the lives of their carvers, is a tour de force. Sometimes she builds on her earlier work. In Northern Haida Master Carvers, for instance, she examined the work of a master whose identity was unknown. Since then her scholarly sleuthing has connected a name — Zacherias Nicholas — and a life story to this prominent figure in Haida art history. For Chicago, he contributed a model of a house for which Wright believes he also painted the front of the full-sized original. She shows off her eye for his oeuvre: “Zacherias’s style of design is characterized by broad angular formlines, very thin negative reliefs, complicated cheek designs, angular and sharply tapering U forms, and hands that have the fingers attached to the concave side of the ovoid.”

Among the more poignant details Wright reveals is a miniature drama no visitor to the Chicago fair actually saw. Inside the model of a house that was so capacious its Haida name translates as “People call to each other in it,” the artist John Cross placed a shaman holding a rattle, flanked by two smaller carved figures. The ceremony was evidently meant to remain hidden. Cross died in 1939, at the age of eighty-five, after a long career working in silver, gold, and argillite — the black stone familiar to collectors of Haida carving. In an interview well after his death, his sons remembered him as a crack shot and a seal hunter, as well as a carver, who fashioned his gun sight out of a gold coin.

Wright offers up many such evocative touches. The composite picture she paints is of a collective art installation of layered complexity, originality, and beauty. Remarkably, it took less than a year to carve the village, ship it from Skidegate to Victoria aboard the steamer Danube, and then deliver it by boat and train to Chicago. A floor plan of the fair’s Anthropology Building shows that the model village’s neighbours included exhibits devoted to Ohio Mound Builders and Grecian statuary. Nearby were the Colorado Cliff Dwellers and Mexican Aztec areas. Not far away, the electric chair from New York’s Sing Sing prison was on display.

Some visitors must have viewed the Skidegate models in the dignified spirit that Putnam intended. But many newspaper reports were thoroughly racist. One described the animal and human figures as “made luridly hideous with paint, daubed and streaked to intensify the ugliness of the carving.” Another was torn between derision and admiration: “After [visitors] have studied the queer looking huts with their heraldic columns, topped off almost invariably by the raven, they go away wondering where the ‘heathen’ of the Northwest coast learned so much about wood carving.”

Yet the collaboration between curators and carvers was ultimately a triumph. The Haida artists did not create the mere facsimiles asked of them; rather, they subtly altered and coded reflections on their culture in an era of extreme stress. The curator Jisgang, Nika Collison, who grew up in Skidegate, writes in the book’s foreword that, “while commissioned during times of duress,” the model village “was built on our peoples’ own terms.” Collison also draws a telling parallel between the Haida rebound and Wright’s academic work: “For decades we have been piecing ourselves, our clans, and our villages back together the same way Dr. Wright pieced the Skidegate House models back together.”

The notion that Haida resilience and museum-based research might be driving in the same direction is far from self-evident. The outright looting of totem poles and other treasures that ended up in institutional collections was indefensible. Still, art historians and anthropologists also learned and preserved. The celebrated carver and painter Robert Davidson first encountered that body of knowledge when he moved to Vancouver from his home village of Masset as a teenager in the mid-1960s. “It was a culture shock to see all these people, and they knew about Haida culture, they knew about Tsimshian, they knew about Tlingits, they knew about Kwagiulth,” Davidson said in 1984. “They were a lot more aware of what my ancestors did than I was.”

Lately the relationship between Indigenous artists and ethnographic institutions shows signs of evolving into a far healthier two-way exchange. A history museum in Berlin, the Humboldt Forum, commissioned Michael Nicoll Yahgulanaas to paint a mural about an 1882 expedition that brought a trove of West Coast objects to the German capital, recasting the episode in light of what smallpox did to the Haida. (Recently Yahgulanaas repurposed the mural into a remarkable graphic novel.) The Royal Ontario Museum in Toronto hired Kent Monkman — the Cree artist celebrated for big paintings in faux-historical styles that deliver wickedly satirical critiques of colonialism — to curate a show called Being Legendary, which displayed artifacts, such as beaded moccasins, in a sort of dialogue with his edgy art. Is it fanciful to see Chicago as a distant forerunner of these recent corrective collaborations?

When the fair was over, Boas was far from done with the Haida. In 1900, he dispatched a young linguistic anthropologist, John Swanton, to British Columbia. Working with local guides and translators, Swanton took down the epic poems that undergird Haida visual arts. Arriving at Skidegate, that once enchanting village, he was aghast by what he found. “The missionary has suppressed all the dances and has been instrumental in having all the old houses destroyed — everything in short that makes life worth living,” Swanton wrote to Boas.

What was lost must have seemed to him beyond recovery. But in the most uplifting passages in Skidegate House Models, Wright shows how the Haida have restored those things that make life worth living. In April 2017, for example, “a memorial potlatch and headstone raising was held in Skidegate for the late Chief Gidansda, Percy Williams (1930–2015), and a pole in his honor was raised on a hill overlooking Skidegate in the playfield outside the George Brown Recreational Centre.” In her respectful way, Wright then lists seven previous hereditary chiefs dating back to the 1870s — the era that all those carvers visualized when they set to work on the model village.

After the fair, the Skidegate models entered the collection of Chicago’s new Field Museum of Natural History, which still has nine of the houses and sixteen poles. The rest were traded, sold, or given away — scattered to Brooklyn, Philadelphia, and Vienna. Most are now lost, making Wright’s meticulous, moving account the closest thing possible to a reconstruction.

John Geddes previously served as Ottawa bureau chief for Maclean’s.