On my family farm is an outbuilding we call “the school.” About twenty-five feet wide and twice as long, it’s used for storage: gardening equipment and the farm truck, a rotation of tractors and other machinery. When I was very young, it held, for several calving seasons, a maternity pen into which cows would be brought to give birth in the relative warmth. The only physical evidence of its past function is a long greenboard that bears a few faded chalk markings.

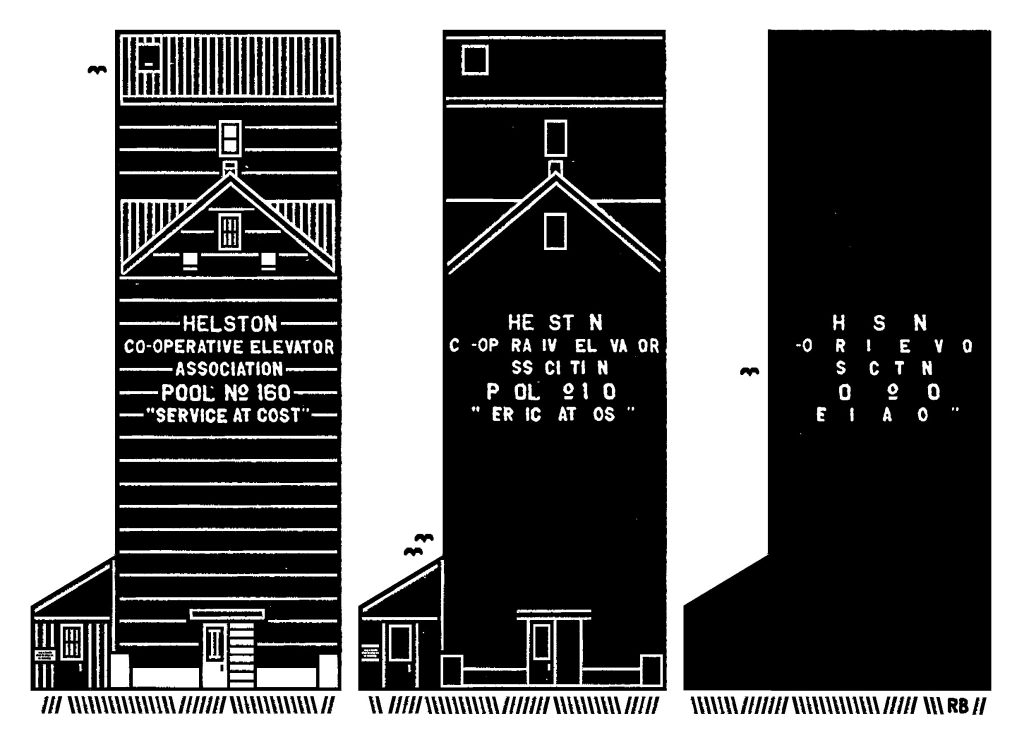

As its name suggests, the building had been, from 1939 to 1967, the schoolhouse in nearby Helston. Very little remains of that Manitoba town, which was never much of a town to begin with. (It was described in 1925 by one railroad agent as only “a little jumping-off place on the C.N.R. out east of Neepawa.”) At its peak, after the Second World War, it had, besides the school, a few houses, a post office, a general store, a dance hall, separate rinks for skating and curling, and a grain elevator to service the many small farms in the area.

The hall, rinks, and post office were levelled in time. The general store became a house (locals still call it “the store”). The school was moved and became our storage shed. In late 1978, the rail line was removed and the grain elevator shuttered. The local paper announced the “uncelebrated closing” and lamented that Helston, like “so many other small and friendly communities,” was falling “victim to growth disease that has captured our farming society.”

Documenting a province’s many sites and stories of abandonment.

Raymond Biesinger

The statement is drastic, but the sentiment — that things are changing and something sinister and uncontrollable is to blame — is heartfelt. The “growth disease” that “killed our villages” undoubtedly referred to the rising acreage of farms, as aging sodbusters with small holdings gave way to rapidly industrializing operations. By the late ’70s, elevators were considered sustainable only if they handled over 400,000 bushels per year. Helston was trading half that amount, and the gangway to its unloading dock could not handle the larger grain trucks then being used. Efficiency trumped community in a pattern that continues today, as smaller farms are purchased and incorporated into larger ones, as elevators increase their capacity, as farmyards are left abandoned across the country.

When Gordon Goldsborough’s Abandoned Manitoba appeared in 2016, I was chuffed to see the Helston elevator in its pages. “A rare treat,” Goldsborough described it from a distance, though, after a closer inspection, he surmised that “if rotting timber does not bring about its demise, a vandal with a match will.”

The book proved popular, and Goldsborough followed it in 2018 with More Abandoned Manitoba. His latest (and, he suggests, his last) instalment in the series is On the Road to Abandoned Manitoba, which follows the structure established by its predecessors. Several dozen “abandoned” sites across the province are presented in glossy photographs, their histories explained in Goldsborough’s chummy, conversational tone, which will be familiar to listeners of CBC Manitoba’s Weekend Morning Show.

“Abandoned” is a tricky definition. A former bank, say, now operating as a laundromat, isn’t so much an abandoned bank as it is a laundromat. Goldsborough, the head researcher and past president of the Manitoba Historical Society, as well as an associate professor of biological sciences at the University of Manitoba, is nothing if not methodical. Thus, while “abandoned” qualifies any site no longer serving its original purpose, inclusion in his series requires that sites also maintain some vestige of their former use, are unique or notable, and are important to Manitoba history.

From residential schools, sanatoriums, fisheries, cemeteries, and telephone exchanges, Goldsborough chooses places that can also stand for some larger movement or moment (in the case of Helston’s elevator, it was the Manitoba Pool Elevators cooperative). Telling the story of their abandonment “imbues them with deeper meaning.”

History does not explain everything, nor does it alone suggest what makes abandoned places so interesting. In the original Abandoned Manitoba, Goldsborough writes that whereas the creation of a site proves some importance, its abandonment shows that its value has slipped away: “That change in attitude is the basis for a story that I want to tell here.” Yet at the end of three books, Goldsborough seems muddled by his own obsession with all things abandoned. “Whatever the psychology behind my interests,” he writes, “it is a deep, abiding passion that I aspire to convey.”

Goldsborough makes the clear observations that abandonment “illustrates a fundamental aspect of life: everything changes” and that “humans are often reluctant to embrace this change.” But he’s not exactly mining new psychological territory: “We find comfort, maybe even safety, when conditions remain constant. Change implies uncertainty and, being inquisitive beings, humans want to know why something has changed so we can be better prepared to resist it. Abandonment may evoke feelings of sadness because we regret the injustice that it implies in the changes it symbolizes.” Of course, that’s not always true, and what precipitates change is too complex for this book of reminiscence. Change is not always resisted, is not always sad or unjust. One person’s greed is another person’s market force, another person’s progress.

What all of these abandoned places tell us, Goldsborough argues, is a story of “what worked and what obviously didn’t.” Those reasons aren’t always clear, and sometimes Goldsborough is left to surmise why a place closed down. Maybe it was a “been there, done that” attitude that ended pleasure cruising on the Red River. Or maybe it was the river becoming identified more with dead bodies than with sunny afternoons. Some closures were bound to happen, like that of the West Hawk Gold Mines, which produced just four bars’ worth in over fifty years, and of the Tilston Coal Shed, which held rock mined from a small seam near Deloraine. Others — the Sargenia Terraces and the Lemiez Sculpture Garden come to mind — were personal follies that drifted into obscurity when their creators died.

There isn’t any “good ol’ days” schmaltz in Goldsborough’s tone, but there is plenty of (rightful) lamenting for when individual innovation and grit met with and lost to insurmountable market forces. For every Haynes’ Chicken Shack that closes, there is a McDonald’s to fill the void; for every folded Pineland Forest Nursery, there is a Walmart.

Should I regret the collapse of Helston? My hometown of Gladstone — one of the “big towns” that outran the village — is now a flagging community itself. Should I mourn the beef ring that my grandfather presided over, splitting steers communally among the neighbours? Or should I be glad it’s gone, given that the few remaining people in Helston would probably fail to raise a single fat calf among themselves? Should I regret I didn’t attend a country school like that in Helston? There is the sentimental pull — my grandmother taught there, and my uncle was a student — but I feel lucky to have missed those rap-on-the-knuckle lessons. My memories of “the school” are different: watching my father fix a two-stroke engine, the viscera of birth, drying root vegetables littering the concrete floor, the tick of the tractor’s block heater in winter.

There is another, greater force at play behind the popularity of these Abandoned Manitoba books than regrets over “growth disease.” We don’t just miss a place: we miss the world it belonged to.

Community is Goldsborough’s main preoccupation. He notes that road development and urbanization have created a “negative feedback loop” that has gutted Manitoba’s (one could say Canada’s) rural areas of people and business. “By making it easier for people to travel from place to place, good roads make it easier for people to commute to and from large communities offering more services than smaller communities,” he writes. “The result is that fewer people are willing to live in small towns and they become ghosts.” (Goldsborough is correct that the rural Manitoban’s view of our capital is that “most Winnipeggers have no idea what lies beyond the city boundaries and are quite happy for it to stay that way.” He stops short, however, of using the condition’s common moniker, “perimeteritis.”)

Once upon a time, before the causeway between Hecla Island and the mainland was completed in 1971, there was a ferry; before the ferry (prior to 1953), any prospective visitors needed to trawl the shore looking for a fisherman willing to take them across. Goldsborough also records that in 1932, a pair of fifteen-year-old hitchhikers going from Winnipeg to Kenora gave themselves two weeks for the return trip. Travel, to use these two examples, took time, conversation, and effort — and conversation with a stranger wasn’t a consequence of failing to plan; rather, it was the plan itself.

Most of the sites featured in the Abandoned Manitoba series come from pre-digital times and are communal in some respect: libraries, clubhouses, rinks, churches, tourist cruise boats, colleges, campgrounds. These are places of collective memory, when community was a necessity for life and not a buzzword tossed around by politicos. Now — whether in the name of ease, indolence, or anxiety — casual interactions with neighbours, let alone strangers, are at an ebb. Alongside streamlined life — in everything from travel to shopping, eating, working, and, amazingly, socializing — came a retreat from community, first into the family unit and then into the self. There is hardly anything we cannot do, cannot receive, cannot learn on our lonesome, thanks to the internet and screen technology. Self-seclusion is no longer for the monkish but for the masses.

Yet Canada has no myth of the lone man. The lone ranger, the mountain man, the lone pioneer, the serial killer: these are constructs of America. No matter how much we wish to replicate them, we remain a country of the collective. Where the American sees exceptionalism, the Canadian is more pragmatic and therefore realistic: the vigilante is not a hero but a criminal; the loner is not a genius but a nutcase.

In our history, it’s what we have done together that defines our nation. Our heroes are people of collective action: Louis Riel, Tommy Douglas, Viola Desmond, Nellie McClung, Frederick Banting. Whatever greatness we have achieved as a nation has been wrung from ideas for and of the collective. An individualized world does not sit well on the Canadian psyche, given the brutal weather, the long distances, the wildlife. We harbour no illusions that anyone can bear these things alone. “Scratch a Canadian,” Margaret Laurence wrote, “and you find a phony pioneer.” We are not a go-alone-into-the-wilderness people. Goldsborough is not explicitly pointing to the fear of solitude (his outlook is far too cheery for that), but it is the emotion that drives the popularity of his books. He is a conduit, coalescing the nostalgic places of others, imbuing them with as much fact as possible.

Goldsborough, for one, is not afraid of strangers. His discoveries across the province are led and informed by locals and enthusiasts, and he bolsters them with historical records made by concerned citizens with a zeal for the past that matches his own. He underscores again and again the need to take stock of the past through our architecture, but few of the structures he mentions are destined for renewal. Most await demolition, and a sizable number are present only in the effect they have left on the landscape: scars on the earth, the rubble of concrete foundations.

At a time when official support for history is waning — the collections and records of the Manitoba Archaeological Society are stored in a car wash in Virden — it is quite often the private citizen who maintains these sites, slowing the passage of time just enough for the past to be recorded. In that way, Goldsborough, too, is making his mark on the preservation of Canadian history.

Note: The grain elevator back in Helston is still standing.

J. R. Patterson has contributed to The Atlantic and many other publications around the world.