A novel that opens with a kidnapping invites certain questions. Who is the victim? Why have they been put in this unfortunate position? Who are the kidnappers? Are they simple villains acting out of greed or spite, or is there (at least in their own minds) a higher motivation at work? The conventions of the crime novel dictate that these questions must be answered in such a way that the ending, when it comes, feels thrilling and organic — the working out of a dialectic between chaos and order. The challenge lies in using surprise and suspense to keep the reader engaged while the grim machinery of the plot grinds on underneath.

It takes self-confidence to subvert these expectations, and Colin Barrett proves himself a self-confident novelist with Wild Houses. It begins when Dev Hendrick, a kind-hearted but aimless high school dropout, gets a visit from the brothers Gabe and Sketch Ferdia, minor gangsters who regularly pay him to store drugs in his shed. This time, they want him to store a person: Doll English. Doll is the younger brother of Cillian, a wiseacre and former dealer who owes money to Mulrooney, the Ferdias’ stoic and terrifying boss. Dev does not particularly want to be party to kidnapping this teenager, but he’s unsure how to say no. The listless “good sitter”— who thinks of himself as “intrinsically unobjectionable, someone who, for better and for worse, could not be singled out in any way”— has made a habit of simply letting things happen to him.

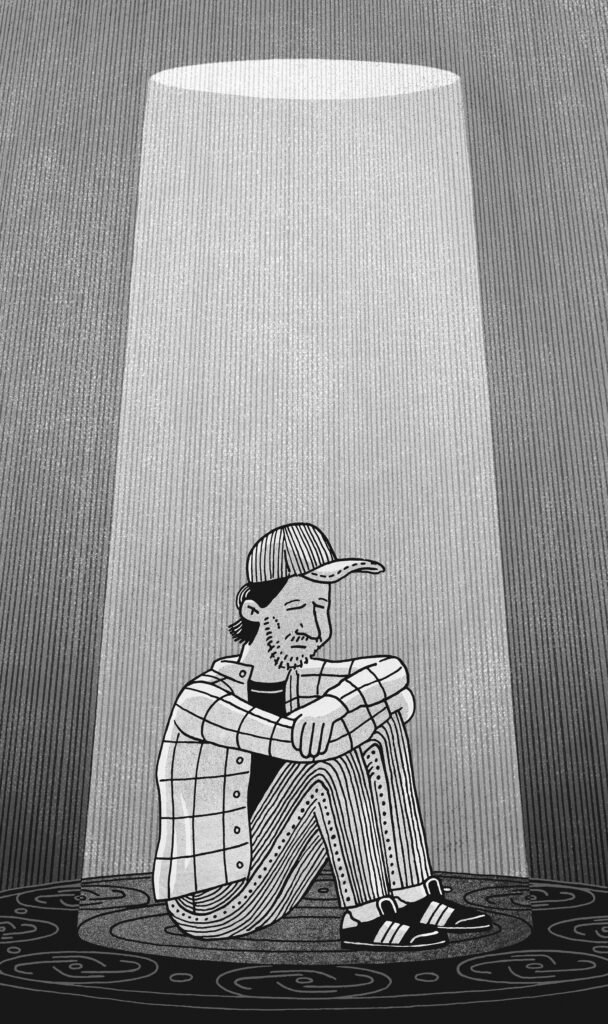

Characters trapped in more ways than one.

Tom Chitty

The next night, Gabe visits Doll’s girlfriend, Nicky, at the pub where she works as a bartender. He gives her an instruction: “You tell Cillian that we have Doll.” The sensible and composed woman is planning on moving to Dublin to study at Trinity College, and she has started to blow hot and cold about her apathetic partner. She initially assumed his disappearance was part of his general unreliability. When she realizes the severity of the situation, she falls in with Doll’s mother, Sheila, and the reviled Cillian to figure out how to rescue her boyfriend.

There’s plenty of action in this novel, but Barrett is less interested in the specifics of the drama than in emphasizing how ordinary such events are for his characters. Like Alice Munro or Flannery O’Connor, he has made a career writing short stories that focus on a particular place and the particular kind of people it produces. In his case, it is Mayo, the largely rural, relatively poor county in the west of Ireland where he grew up. (Barrett was born in Canada but moved abroad with his family as a child.) Violence and criminal activity are not outside forces to be held at bay in the Mayo of Barrett’s fiction. They are aspects of regular life that everyone will experience at one point or another. The “wild houses” of this book’s title are lawless zones where drugs are sold and parties never end, but they exist side by side with ordinary suburban dwellings. Every day, residents of Mayo must negotiate the lines between licit and illicit, intoxication and sobriety, mental health and mental illness.

That said, Wild Houses is not really a novel about crime. It is a novel about fate. At times, it seems as if Dev, the Ferdias, Doll, Cillian, and even Nicky are acting out scripts that were written before they were born. They can change where they live. They can change what they do. But they can’t change who they are. Sinister Gabe managed to kick heroin, yet he still drinks like a fish and relies on gangsterism as a way of life. Dev is sensitive and intelligent enough to know that he is adrift and miserable, but he inevitably winds up “back where he always seemed to end up.” His life is forever “circling, tighter and tighter, in on itself.” As for Nicky, there is never any question that she will eventually leave town and leave Doll. This sense of the self as a prison is described most pungently by Cillian. “Believe it or not, I know what I’m like,” he says. “Every so often, it dawns on me, in cold horror.”

Barrett’s prose is artful. He’s particularly strong with descriptions, and he has a fantastic ear. His characters are Irish and sound Irish on the page — not an easy accomplishment. After centuries of colonial oppression and class hierarchy, spoken English is highly politicized across this archipelago that Barrett and I call home, and a writer who relies heavily on dialogue, as Barrett does, needs to chart a difficult course. Go too far in one direction and you lose the sense of authenticity. Too far in the other, you risk landing in leprechauns-and-shamrocks territory. In its best moments, Wild Houses uses the music of speech to masterfully root the narrative in place.

Barrett’s approach to dialogue isn’t flawless, however. He has a somewhat maddening habit of writing entire conversations verbatim — down to the greetings and farewells. Many discussions continue ad nauseam, sometimes going for whole chapters. Characters reveal important pieces of information in these exchanges, but there’s an awful lot of verbal padding:

“What’s your name?”

“My name?” Doll said.

“If you don’t mind.”

Doll looked dubiously across at Nicky and back at the man.

“Donal,” he said.

“Donal what?”

“English.”

“Well, there you go!” the man said brightly. “Vincie English would be your father.”

“Yeah.”

It’s true that this is how conversations in real life tend to go. But the effect when you transpose such speech onto the page is exhausting.

Barrett runs into a similar problem when he describes people going about their business. They are constantly opening and closing doors, turning on taps, pouring drinks, and walking down hallways. A more charitable critic might argue that such descriptiveness grounds the story in reality. I couldn’t help feeling that all this stage business sapped the novel’s energies and dulled its sharpest edges. By the end, I was tempted to skim. And I hate skimming.

Unsurprisingly, Wild Houses ends with an anticlimax. The plot resolves with a couple of neat little thuds, and it is clear from the final chapters that the characters we have been watching for a few days will continue along their trajectories, fundamentally unchanged by the experience. Barrett recognizes that most of us will have the same basic problems ten years from now that we have today because such problems are part of who we are. Maybe there’s something admirable about that acceptance.

André Forget is the author of In the City of Pigs. His new Substack is called Oblomovism.