The day after the 2016 United States presidential election, the team behind New York Public Radio’s On the Media recorded an editorial meeting that was then broadcast to its million-plus weekly listeners. In a raw and unfiltered segment, the hosts, Brooke Gladstone and Bob Garfield, and their executive producer, Katya Rogers, processed feelings of shock and fear and anger, contemplated mistakes they may have made covering Donald Trump’s campaign, and pondered how they might approach the new administration. Given that they believed Trump’s presidency was a “historic threat to our democracy and to our values,” the central dilemma, as articulated by Garfield, was whether the show should continue moving in the direction of advocacy journalism —“amp up the skepticism and outrage”— or whether they should pull back as more dispassionate observers.

“Do we try to approach our jobs as leaders of a movement for truth and justice?” Garfield asked. “Or do we just try to do our jobs as journalists covering journalism, and let the rest sort itself out? I’m not sure we can do exactly both at the same time.” To which Gladstone replied, “I guess I would say I think we can do exactly both at the same time.” A type of conversation that typically happens behind closed doors was taking place out in the open, and audiences were listening as new editorial standards seemed to take shape.

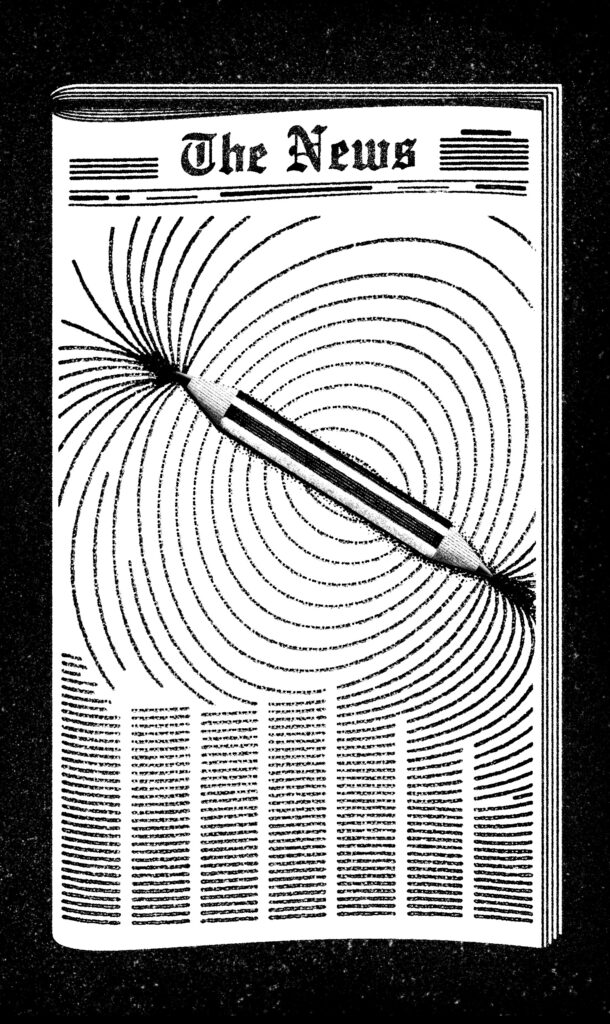

Yes, there are still two sides to a story.

Karsten Petrat

Those eighteen emotionally charged minutes of radio effectively took an emerging opinion — that Trump was dangerous and covering him ethically necessitated an abandonment of the news media’s characteristic detachment — and placed it squarely within the mainstream. The segment sent ripples out to the furthest reaches of the North American press corps, to journalists who didn’t even hear it and likely never would. It helped usher in an activist-oriented era in media, one that wreaked havoc on journalism’s credibility and set in motion an accelerating downward spiral of trust that continues to this day: according to the latest data from Statistics Canada, just 16 percent of Canadians report “a high level . . . of trust in information and news from the media.”

Understanding this spiral is essential for making sense of the crisis in Canadian media and for forging a sustainable path forward for our fourth estate. To unpack it, we must begin by looking at its origins in the U.S. and the hysteria that initially drove it.

An existential crisis. Leading up to the 2016 election, the U.S. media collectively lost its cool. Trump had long been a source of entertainment, a smug punchline, a ratings boon. But as election day neared, his habit of disparaging the press began to grate, and his knack for dominating the news cycle with outlandish claims started to raise legitimate alarms. The feeling that Trump was an extraordinary candidate, and that ordinary journalism was insufficient to the task of covering him, began to solidify.

David Mindich, a journalism professor at Saint Michael’s College in Vermont at the time, detailed a “launch moment” for the shift in the Columbia Journalism Review, noting in July 2016 a change in tone among the likes of Megyn Kelly, Anderson Cooper, and Jake Tapper, who had all become more openly confrontational. Mindich characterized the conundrum facing the press corps as a “Murrow moment,” in reference to Edward R. Murrow, the CBS newsman who famously set aside his own detachment to speak out against Joseph McCarthy in 1954: “If a politician’s rhetoric is dangerous, Murrow implied, all of us, including journalists, are complicit if we don’t stand up and oppose it.”

Writing in the New York Times the following month, Jim Rutenberg was even more explicit. “If you’re a working journalist and you believe that Donald J. Trump is a demagogue playing to the nation’s worst racist and nationalistic tendencies, that he cozies up to anti-American dictators and that he would be dangerous with control of the United States nuclear codes, how the heck are you supposed to cover him?” Rutenberg asked. “If you view a Trump presidency as something that’s potentially dangerous, then your reporting is going to reflect that. You would move closer than you’ve ever been to being oppositional.” Rutenberg conceded that would be a move into “uncharted territory for every mainstream, nonopinion journalist I’ve ever known, and by normal standards, untenable.”

The verdict was in: These were not normal times. Extreme threats called for extreme measures. Trump triggered an existential crisis in the press, and many observers were terrified by what they saw as creeping fascism. The media panicked and pulled down its guardrails, a move that many argued was justified by the exceptional circumstances. Guardrails exist for a reason, though, and discarding them came with unintended consequences. Consider, for instance, the newsroom taboo against labelling a politician’s false statement a “lie,” since the word is inflammatory and denotes not only an untruth but an intent to deceive, which is hard to prove. Ahead of the 2016 election, the Times opted to use that word in headlines about Trump. While Liz Spayd, the paper’s public editor at the time, agreed that it was warranted in select cases, she cautioned colleagues that it should be used sparingly: “Its power in political warfare has so freighted the word that its mere appearance on news pages, however factually accurate, feels partisan.” Indeed, many had reservations about using “lie” at all. As the investigative reporter Matt Taibbi said in a CBC documentary that aired in 2021, “Once you take that step into becoming kind of a political actor instead of a journalist, the problem is you can’t go back.”

And that is exactly what has happened. The erosion of journalistic norms and practices did not remain limited to Trump coverage or even to the Trump era. Instead, new emergencies have continually emerged: Russian interference, #MeToo, the pandemic, the racial reckoning, and so on. The exception has become the rule. “The media in the last four years has devolved into a succession of moral manias,” Taibbi wrote in 2020. “We are told the Most Important Thing Ever is happening for days or weeks at a time, until subjects are abruptly dropped and forgotten, but the tone of warlike emergency remains.” With each new cause for alarm and each new reason to take a strong stand, the media has been pushed further down the slippery slope of activism. “We’re living in times where everything is overblown and dire and an emergency,” David Greenberg, a professor of history and journalism at Rutgers University, told me in 2022. “In that context, there’s a sense of desperation — that we need to assert moral truths, unambiguously.”

Such an imperative inevitably leaves us open to “ideological capture,” when an ideology assumes disproportionate influence over, in this case, a newsroom and its operations. It stifles critical thinking and paves the way for factual errors, which engender hostility among the public. In the face of that mounting anger, we double down on certainty, refusing to admit mistakes lest we cede ground to actors or ideas that we consider malevolent — thereby further eroding norms and practices. Such behaviour leaves the citizens we’re meant to serve ever more distrustful of our work. And with each new downward cycle, they abandon us in ever greater numbers. Our credibility, our morale, and our ability — both emotionally and financially — to calmly evaluate the facts are diminished, which makes us more desperate, more anxious.

This anxiety of ours, it must be said, predates Trump. Indeed, the unravelling of trust in the media would not have been possible if our business had not already been on the edge of a precipice when he got into politics — if individual journalists’ lives and the state of entire media organizations were not already so precarious.

So the first stage of the trust spiral is not political at all but economic.

A failing business model. There’s an old saying about how you go broke, the journalist Jen Gerson told me last summer: “Slowly, slowly, and then all at once.” The co-founder of the news commentary site The Line, Gerson noted that the Canadian media has gradually been going broke for the past two decades — and now it’s all collapsing simultaneously. Indeed, the business on both sides of the border has been grappling with catastrophic declines in revenue, mass layoffs, and outlet closures for years. The bill has finally come due.

This past January alone offered ample evidence. “For a few hours last Tuesday, the entire news business seemed to be collapsing all at once,” Paul Farhi wrote in The Atlantic, lamenting layoffs at Time, National Geographic, and the Los Angeles Times. Sewell Chan, editor-in-chief of The Texas Tribune, a non-profit site, told Farhi that he worried 2023–24 could see an “extinction-level event” not unlike the 2008 recession. So far, it’s looking like Chan is right. The downsizings were followed, as the publisher Ken Whyte pointed out in his weekly newsletter, SHuSH, by cuts at Business Insider and the folding of the well-funded American start‑up The Messenger. The shuttering of Vice.com came next. In Canada, our market was reeling from the news that Bell was laying off 4,800 employees, roughly 10 percent drawn from its media division, and selling off forty-five regional radio stations, halting most weekday lunchtime newscasts on CTV, and ending many of its nightly newscasts.

Today Canada has between 8,000 and 12,000 journalists, covering a country of 41 million. Many work at our national public broadcaster, whose future is uncertain; a recent Spark Advocacy poll found that 45 percent of Canadians were drawn to the idea of shutting down the CBC to save tax dollars. What’s more, according to Toronto Metropolitan University’s Review of Journalism, the CBC employs more than 2,000 temporary and contract workers on any given day (including, in the past, me). In other words, roughly a fifth of our journalists have zero stability in their lives. The rest live in constant fear of being laid off. Our press corps is perpetually stressed, terrified of making even the most minor of missteps. This kind of precarity has profound consequences.

For much of the twentieth century, the news media enjoyed well-staffed newsrooms, large audiences, and robust advertising revenues — until the advertising business model began to implode with the rise of the internet. First, Craigslist rendered the classified sections of newspapers obsolete, decimating a reliable and crucial money-maker. Next, particularly in the aftermath of the 2008 recession, print publications lost commercial ad revenue. And as tech giants like Facebook and Google broke ground on digital advertising, offering targeted ads with detailed analytics, even more dollars went out the door. “I think people have underestimated the size of this disruption,” Peter Menzies, a former vice-chair of the Canadian Radio-television and Telecommunications Commission, told me recently. “It’s analogous to the invention of the printing press.”

As the massive disruption unfolded, the range of content available online exploded, attention spans fragmented, and the public began turning off television news. As Taibbi has detailed in his book Hate Inc.: Why Today’s Media Makes Us Despise One Another, to compete for elusive eyeballs, TV executives began targeting specialized demographics. Fox News went after conservatives; then MSNBC used the same formula to cater to liberals. The combined effect was a media ecosphere with more opinion, more outrage, more division. “We have today a very polarized media environment,” Batya Ungar-Sargon, an opinion editor at Newsweek, told me in 2022. “But it’s polarized only on behalf of . . . rich liberals and rich conservatives.” For the vast majority of Americans, she continued, “the media is just not talking to them, or about them, or about anything they care about. They’re completely checked out, and they’re increasingly boycotting the mainstream media.” I agree with Ungar-Sargon that this is a disaster for democracy.

Because the business model for the news used to be based on attracting as large an audience as possible, outlets reported the news down the middle. But as that model collapsed — and as an engagement-driven one emerged — digital outlets were incentivized to cultivate niche audiences. Since the most extreme audiences were also the most engaged, this new business model rewarded content that appealed to between six and eight million Americans, the fringe of an already tiny demographic, Ungar-Sargon estimates in her book Bad News: How Woke Media Is Undermining Democracy. Then, as the engagement model itself began to fail, a small group of marquee outlets successfully transitioned to subscriber models by cultivating urban, educated audiences, who were willing and able to pay for content — including the 10.4 million who pay for the New York Times and the 330,000 or so who pay for the Globe and Mail. (The Globe is privately owned, but Phillip Crawley, its recently retired CEO, has testified before the Senate about its subscribers, the majority of them digital.) Most others floundered. Jobs were slashed and operations were consolidated. Local news increasingly disappeared, and investigative reporting — the most expensive and time-consuming form of journalism — declined. The newsrooms left standing were significantly weakened, as was the quality of their coverage.

Predators also moved in. Hedge funds bought up newspapers, sold off real estate, and extracted as much money as possible from assets. They laid off staff, leaving skeleton teams in place. “Papers eventually are driven into the ground,” as Sohrab Ahmari, a co-founder of Compact magazine, explained on my podcast, Lean Out. “But more often, private equity holds on to them as ghost papers. Ghost papers typically do a lot of vacuous, advertorial-type content. Then, in between, they run mostly national coverage. Because national coverage is easy to syndicate across many papers.” The problem is the loss of “the local media watchdog function, and that element of local media as being crucial to the local democratic conversation.” (If a paper shuts down entirely, a community pays what amounts to a “corruption tax,” to repeat a phrase the former Boston Globe editor Ellen Clegg has used. “There’s no watchdog watching the local budget.”)

Gerson, who used to work at the Calgary Herald, prefers the term “zombies.” By the time she left, she was writing straight to the page, without her copy being checked by editors. “Typos went up, errors went up,” she told me. “As the editing process collapsed in on itself, the institutional judgment and norms that had been established from the previous century of journalism — that came under threat.”

If reporters can’t even trust their own product, how can we expect the public to?

In such a climate, the training of young journalists naturally suffers. And that is key to understanding the mess we’re in. Journalism is not something you can learn at university, Holly Doan, the publisher of Blacklock’s Reporter, recently told me. You need to apprentice. The consolidation of media and the disappearance of smaller outlets have meant fewer chances to do what Doan did: train for years at local publications and then regional ones, living in communities across the country before arriving in Ottawa to cover national stories. “That doesn’t happen anymore. Now you have journalists who go to journalism school, where they’re not taught anything about covering courts or local council,” she said. “The skills are gone. Journalism isn’t dying. On the ground level, it’s dead.”

A generational shift in skills has been compounded by a generational shift in class background. Journalists entering newsrooms these days are highly educated, often with multiple degrees. Competition-induced credentialism, coupled with the requirement to undertake internships in our most expensive cities, favours young people from economically privileged families. This trend has reduced the economic diversity of our newsrooms and thus the range of perspectives. It has reinforced the perception that the media belongs to society’s elites, despite its dismal financial prospects.

Media consolidation has obviously led to geographic consolidation, with many journalists now based in urban centres and cut off from the range of views elsewhere in the country. (How, Doan asked me, can a journalist cover a farm subsidy program if they’ve never even met a farmer?) A less obvious factor in the diminishment of newsroom functionality, however, is the exponential growth of the public relations industry. As the University of Winnipeg professor Cecil Rosner observes in Manipulating the Message, Canadians working in PR now outnumber journalists by a ratio of about thirteen to one. That makes daily journalism more difficult to perform, as teams of professionals stand between reporters and those they report on, necessitating lengthy negotiations over access.

The digital publications that initially found success during the 2010s, largely funded by private capital, often prioritized viral spread over truth seeking — emphasizing instead confessional essays, listicles, and off-the-cuff opinion pieces driven by outrage (headlines like “This Brave Woman’s Horrifying Photo Has Become a Viral Rallying Cry against Sexual Harassment” and “The Problematic Disney Body Image Trend We’re Not Talking About”). This type of work requires little expertise to produce — and no reporting. The more desperate legacy outlets became, the more they recruited the “digital natives” working for content farms, hoping they could reliably generate traffic. And as the decade wore on, these young journalists were increasingly influenced by a niche political culture that got enormous traction on social media.

It was this new ideology that truly accelerated the media’s trust spiral.

Ideological capture. In his book Canceling Comedians While the World Burns, the philosopher Ben Burgis describes a YouTube clip from a 2019 Democratic Socialists of America convention. In it, the gathering is repeatedly disrupted by delegates who complain about fellow participants standing (too distracting), whispering (too triggering), and wearing cologne and perfume (too aggressive). They ask that delegates avoid clapping (jazz hands work just fine) and gendered language like “guys.”

The video, which of course cherry-picks moments from many hours of a live-streamed event, was gleefully mocked on conservative media platforms. But it does demonstrate, Burgis argues, the gap between many far-left activists and mainstream public opinion. I’d say it also illustrates, albeit in a comically exaggerated way, a belief system that has taken over not just progressive politics but many of our most influential institutions, from the arts to education.

This set of beliefs has proven remarkably resistant to critical evaluation for several reasons. First, because it brands itself as a social justice movement, and few people are against the idea of a just society. Second, because it presents its ideas as moral imperatives — as basic human decency — and few want to be considered immoral. Third, because its adherents contest attempts to name their movement, arguing that the term “woke” is a slur and that those who use it are not able to define it, which obviously makes the movement harder to discuss. And fourth, because its more extreme members tend to shut down debate entirely, with vicious campaigns of online shaming. “What we have actually seen develop in the States,” the podcaster and media entrepreneur Kmele Foster told me in 2020, “is a real appetite right now to punish people who have bad ideas. And the universe of things that are considered bad, objectionable ideas is expanding at a pretty rapid clip.” As Chloe Valdery, who developed the Theory of Enchantment anti-racism training program, said in a separate conversation that same year, “Complexity of ideas, and the ability to hear from people who we disagree with, is critical for a functioning democracy.”

So unpacking the ascendant ideology remains an important task, despite its many minefields. We can begin by using as neutral a term as possible: “identitarian moralism.” And we can attempt as neutral a definition as possible: a political philosophy that examines social inequalities through the lens of identity and considers it a moral obligation to dismantle group disparities.

Having established what is, in fact, a definable political ideology, we should then feel free to evaluate it critically, as we would any other. In doing so, we might notice that while identitarian moralism is radical on social issues like race and gender, it does little to challenge the economic status quo, which may be why it’s been embraced by so many corporations. We might also observe that while it presents itself as leftist, it dispenses with key tenets of the left, from universalism to free speech, and ignores material conditions and class analysis. In many ways, identitarian moralism actually disdains the working class, whose members fail to conform to its ever-shifting mores. What do these mores involve? Transforming language and speech norms; interrogating interpersonal relationships; problematizing pop culture; increasing the representation of marginalized groups in elite spaces; enforcing symbolic gestures such as land acknowledgements; enacting diversity, equity, and inclusion training sessions; and building up an identity-focused bureaucracy to advance these efforts.

I point all this out because identitarian moralism is particularly prevalent among media workers, as the Marxist writer Freddie deBoer noted in a scathing essay in 2021. “In the span of a decade or so, essentially all professional media not explicitly branded as conservative has been taken over by a school of politics that emerged from humanities departments at elite universities and began colonizing the college educated through social media,” he wrote on Substack. “Those politics are obscure, they are confusing, they are socially and culturally extreme, they are expressed in a bizarre vocabulary, they are deeply alienating to many, and they are very unpopular by any definition.”

DeBoer asked, “Why does no one in media seem willing to have an honest, uncomfortable conversation about the near-total takeover of their industry by a fringe ideology?” (It was as if, he told me later, “the whole media crawled into a very narrow hole.”) The author of How Elites Ate the Social Justice Movement, deBoer is hardly the only leftist thinker to blast this brand of progressive politics. The socialist philosopher Susan Neiman has also published an influential book, Left Is Not Woke, and the Marxist scholar Adolph Reed has written extensively on the topic. So too have others across the political spectrum, including John McWhorter, Coleman Hughes, Yascha Mounk, Noah Rothman, Andrew Doyle, and Irshad Manji. Identitarian moralism has attracted so much attention in recent years that the Canadian political scientist Eric Kaufmann has even launched a course on it.

Although many journalists in this country reject the idea that identitarian moralism has a significant influence on our coverage, its impact can be quantified in several ways. A year ago, for example, Aaron Wudrick and David Rozado published Northern Awokening: How Social Justice and Woke Language Have Infiltrated Canadian News Media, a study for the Macdonald-Laurier Institute, in which they analyzed more than six million news articles and opinion pieces published in Canada between 2000 and 2021. What they saw was a dramatic rise since 2010 in social justice vocabulary, with terms relating to gender-identity prejudice in particular increasing by a staggering 2,285 percent.

Similarly, the University of Guelph political scientist Dave Snow has tried to empirically test any progressive bias at the CBC, examining its coverage of Saskatchewan’s 2023 parental consent policy for gender pronouns in schools as a way of understanding its coverage of “contentious social policy disputes,” as he phrased it in a piece for The Hub. Snow found that in thirty-eight articles, “the CBC quoted more than five times as many critics of Saskatchewan’s policy as supporters.” Just 16 percent of the pieces quoted at least one supporter of the policy, compared with 95 percent that quoted at least one critic.

Yet another way to assess the ideology’s influence is to listen to independent journalists, who are less constrained in what they can say publicly. Several prominent ones have begun to speak up about the dominance of identitarian moralism. “The CBC is not contributing to consensus reality,” the writer Stephen Marche has said on Canadaland, for instance. “It is an ideologically captured institution that is listened to by an increasingly fewer number of people — exactly because it does not reflect Canadian reality.” To which the political journalist Paul Wells added, “I hear Stephen’s complaint from a substantial number of the CBC employees I know.”

If we can agree that identitarian moralism is indeed influential within our media, we should then ask how representative it is of public opinion. And the answer is: Not very. Kaufmann has shown this to be the case in the United States and the United Kingdom. More recently, in another Macdonald-Laurier Institute study, The Politics of the Culture Wars in Contemporary Canada, he confirms that those who subscribe to this belief system are also in the minority here — by a ratio of about one in three — despite having an outsized impact on the public conversation. In an email, Kaufmann told me that we actually have higher trust in the media than Americans and Brits, though he thinks that level is likely to go down, since younger Canadians trust journalists less than older Canadians do. “I suspect Canada is at an earlier point in the cycle of decline, and expect to see Canadian journalism lose its innocence more in the years to come,” he wrote. “This will make it more difficult for the Canadian elite to diverge quite so sharply from the country’s public opinion as it has on ‘culture wars’ issues around race and gender.”

Here’s what we as journalists must face: Most Canadians are not progressive activists, and most don’t subscribe to progressive activist beliefs. It follows, then, that the media’s overrepresentation of an identitarian viewpoint does not help us earn back the public’s trust. Privately, a great many journalists already know this. So why have relatively few come out and said it? To answer that question, we must return to the American media — and to a series of upheavals in high-profile newsrooms.

A leadership vacuum. Every generation of journalists has a defining moment. For the current generation, that moment is the death of George Floyd, captured by a teenage bystander in a gut-wrenching video on May 25, 2020. When the images hit the internet, they shocked the country — and indeed the world — uniting people of all political stripes and sparking some of the largest, most multiracial, and most hopeful demonstrations in American history. As the days wore on, though, tensions escalated. Other videos began to circulate online, showing police wielding tear gas and batons. In some places, protests erupted into rioting, arson, and looting. A dozen people died in the first week and a half. The nation’s initial optimism gave way to something else, something far more combustible. “It was like all hell broke loose,” Michael Powell, formerly of the New York Times and now of The Atlantic, told me. “I mean, all hell broke loose in the culture, but also within the newsroom.”

Ten days after Floyd’s death, the Times opinion section published an op‑ed by Tom Cotton, in which the Republican senator from Arkansas referenced violence against the police in St. Louis, Las Vegas, and New York State. Given that officers had been shot at and run over by cars, he argued, an “overwhelming” military response was necessary “to disperse, detain and ultimately deter lawbreakers.” The piece proved explosive, not least within the paper itself. Within hours, Times journalists took to Twitter to argue that publishing it put Black staff in danger.

A thousand staff members then signed a letter addressed to management, including to James Bennet, the head of the opinion section. Bennet believed it was important to hear from Cotton, whose view was influential with the White House. But the paper’s staff disagreed. “Although his piece specifically refers to looters as the targets of military action,” the letter read, “his proposal would no doubt encourage further violence. Invariably, violence, official and unofficial, disproportionately hurts black and brown people. It also jeopardizes our journalists’ ability to work safely and effectively on the streets.”

The NewsGuild of New York was involved in organizing the letter. “I was a shop steward in the union,” Powell, who did not sign the letter, recalled last year. “I argued that this was antithetical to journalism. That an op‑ed page in particular — and, in particular, frankly, at a liberal paper like the New York Times — that it was incredibly important to hear from people like Tom Cotton. Even if you 100 percent disagree with him.”

“I have a lot of respect for A. G. Sulzberger,” Powell told me, in reference to the paper’s publisher, “and for Dean Baquet, who was, I think, largely a terrific editor. But I did think in that moment they came up short. And that there was a need to express the importance of values. There was a need to stand up to that tide.”

Instead, Times management backed down, saying the column failed to meet editorial standards and affixing a lengthy editor’s note to the piece, explaining that the process had been rushed, should have paid more attention to “factual questions,” and had not sufficiently involved senior editors. (Adam Rubenstein, the editor who handled the column, later contested this explanation in The Atlantic, writing that “it wasn’t rushed,” that “senior editors were deeply involved,” and that “there were no correctable errors.”)

Erik Wemple of the Washington Post has characterized the Times controversy as “one of the most consequential journalism fights in decades.” Writing more than two years after the uproar had died down, he blasted the editorial note, which apologized “for nonfactual issues,” and remarked that “a more pathetic collection of 317 words would be difficult to assemble.” The respected media critic also took the staff’s Twitter protest to task. “It was an exercise in manipulative hyperbole brilliantly calibrated for immediate impact,” he wrote. “TheErik Wemple Blog has asked about 30 Times staffers whether they still believe their ‘danger’ tweets. . . . Not one of them replied with an on-the-record defense.”

His own criticism, Wemple acknowledged, came 875 days too late. It was, he wrote, “long past time to ask why more people who claim to uphold journalism and free expression — including, um, the Erik Wemple Blog — didn’t speak out then in Bennet’s defense.” Wemple’s explanation was nothing short of breathtaking: “It’s because we were afraid to.”

Indeed, few journalists summoned the courage to defend Bennet, who was forced to resign, or Rubenstein, who eventually left. In an open letter five weeks after Bennet’s departure, Bari Weiss, an opinion editor who had worked under him, explained why she too was leaving: “Showing up for work as a centrist at an American newspaper should not require bravery.” Weiss argued that the lessons that should have been learned from Trump’s election —“lessons about the importance of understanding other Americans, the necessity of resisting tribalism, and the centrality of the free exchange of ideas to a democratic society”— had simply not been learned. “Stories that are inconvenient to the progressive political project are overlooked or ignored or explained away,” she later told me. “And I think that is doing an incredible disservice to readers.”

By the end of 2021, the industry had been shaken by months of internal newsroom revolts. The editor of Bon Appétit resigned over an old Halloween costume; the editor of Refinery29 resigned over accusations of an unhealthy workplace; the editor of Variety was placed on leave for calling a freelancer “bitter” on Twitter. More upsets at the Times followed, including controversies involving the podcast producer Andy Mills and the science reporter Donald McNeil. Lee Fang, then a reporter for The Intercept, was disciplined for posting an interview with a Black Lives Matter protester who questioned why Black lives mattered only when it was white men who killed them, because the sentiment was deemed racist by one of Fang’s colleagues. “I couldn’t believe they were coming for the man’s job over something I said,” the protester told Matt Taibbi. “It was not Lee’s opinion. It was my opinion.”

Here in Canada, we saw our own high-profile shakeups, including a scandal in June 2020 involving the CBC broadcaster Wendy Mesley. “After George Floyd’s murder last May, a Black CBC reporter tweeted that she had repeatedly been called the N‑word,” Mesley wrote in the Globe and Mail a year later. “I was furious. I wanted to put her on the air to discuss that, and said so in a conference call with producers for The Weekly with Wendy Mesley. During our discussion, I was so upset over what our colleague experienced that I stupidly filled in the N‑word.” Mesley maintained that she immediately apologized, but a subsequent investigation unearthed another instance when she had used the word — this time repeating a book title in a meeting. Mesley’s show was cancelled, and she eventually parted ways with her employer of thirty-eight years. “After a year of reflection and a whole range of emotions,” she wrote, “I’m left feeling mostly disappointed, because this could have been handled so differently.”

Another headline-making incident involved Jamil Jivani, a former iHeartRadio host (elected as a Conservative member of Parliament in March), who was fired by Bell. The telecommunications giant, in a statement of defence in the resulting wrongful dismissal suit, said that Jivani had failed to sufficiently push back on anti-vaccination and anti-government sentiments, had declined to use the pop star Demi Lovato’s preferred pronouns, and had exhibited an “open disdain” for Bell’s diversity initiatives: “The Plaintiff refused to participate in any of Bell’s DEI initiatives, suggesting instead that [Bell] ‘demonstrate a commitment to true diversity: diversity of thought.’ ”

Jivani, who was hired in the summer of 2020, told me that he saw the radio gig as an opportunity to showcase the wide range of perspectives within the Black community, which he felt was being overlooked by the mainstream media. “We don’t all think the same,” he said. “We weren’t all out there marching with Black Lives Matter — in fact, the vast majority of us were not.” Jivani said it soon became obvious that Bell had a very different approach to diversity and that arguments for a more nuanced approach seemed unwelcome in meetings. He felt the climate was not conducive to open dialogue, particularly on sensitive issues like race relations: “I think a lot of people are scared.”

Many have since argued that the newsroom purges of 2020 did indeed create a profoundly illiberal environment, including Michael Lind, a political scientist and co-founder of the New America liberal think tank. “It does remind you of the Soviet Union, or of a totalitarian state, in which you make one false statement, you make one reckless remark, and you’re ratted out,” Lind said when we discussed the industry. “And not to the secret police, but to the HR department.” It was such illiberalism that James Bennet focused on in his own account of the upheavals of 2020, in a lengthy piece for 1843, a magazine published by The Economist. “The Times ’s problem has metastasised from liberal bias to illiberal bias,” he argued, “from an inclination to favour one side of the national debate to an impulse to shut debate down altogether.”

All told, the purges of 2020 had a chilling effect on newsrooms throughout North America, sending a strong message to journalists that if they wanted to stay employed, they’d best proceed with extreme caution. But extreme caution does not foster a healthy newsroom culture, which requires daily debate. Without respect for disagreement, monocultures develop and newsrooms become echo chambers that have little connection to the wider public. The purges sent a signal, too, to the rank-and-file that leadership was more likely to appease radicals than to stand up to them, so journalists began to avoid confrontations with activist colleagues.

In this climate, an idea that had been smouldering for years caught fire. And it was this idea that finally set the trust spiral ablaze.

A rejection of objectivity. In his account of the Times newsroom revolt, Ben Smith, the paper’s former media critic, started not in June 2020 but on August 14, 2014, in Ferguson, Missouri. Wesley Lowery, a twenty-four-year-old reporter with the Washington Post, had woken up that morning — his face aching from having been pushed into a soda machine during an arrest the night before — and dialled in for an appearance on CNN. When the host relayed advice from MSNBC’s Joe Scarborough — that Lowery should move along faster next time police issued instructions to evacuate — he got angry. Lowery described a dystopian scene on the ground and invited Scarborough to “get out of 30 Rock where he’s sitting sipping his Starbucks smugly” and visit Ferguson for himself. “This is a community in the United States of America where things are on fire,” he fumed. Lowery’s dressing down of Scarborough earned applause on Twitter.

Smith’s choice of anecdote illustrated a number of themes that were simultaneously unfolding a decade ago: the tensions between reporters and officers; the shock that many young journalists felt encountering a militarized police force in the streets; the nascent Black Lives Matter movement, which would find many supporters among the press; and the generational shift away from a deference to authority and toward a new outspokenness, turbocharged by social media.

By the summer of 2020, Lowery had become a bona fide media star and had won a Pulitzer Prize. He’d also been pushed out of the Post, by its legendary editor Martin Baron, over his social media use. Not surprisingly, when Tom Cotton’s op‑ed appeared, Lowery quickly entered the fray, tweeting, “American view-from-nowhere, ‘objectivity’-obsessed, both-sides journalism is a failed experiment. . . . We need to rebuild our industry as one that operates from a place of moral clarity.” Later that month, he published an op‑ed of his own in the Times, arguing that the news business should move beyond objectivity and adopt a “method of moral clarity.”

It would be difficult to overstate the impact of Lowery’s idea. It effectively ushered in a new era — indeed a new standard — in journalism. At The New Yorker, Masha Gessen wrote a widely discussed essay, “Why Are Some Journalists Afraid of ‘Moral Clarity?’ ” Lewis Raven Wallace, who’d been fired from the public radio show Marketplace for penning a blog proclaiming objectivity dead, saw renewed interest in his work, including The View from Somewhere, published the previous year. In Canada, similar calls to question the role of objectivity followed, including an award-winning Walrus essay by Pacinthe Mattar, “Objectivity Is a Privilege Afforded to White Journalists,” and a prestigious journalism lecture by Denise Balkissoon, the executive editor of Chatelaine at the time. The University of British Columbia journalism professors Candis Callison and Mary Lynn Young advanced this view, too, with a book called Reckoning: Journalism’s Limits and Possibilities.

David Greenberg, writing in the quarterly Liberties two years ago, argued that “newly fashionable phrases” like “moral clarity” should make us pause, “not only because they were first popularized by Bush during the war on terrorism, but also because determining the correct moral posture on a political or policy issue is almost always difficult.” It was certainly, he suggested, “beyond the capacity of a daily journalist working at digital speed.” If we led with moral convictions before we determined what had happened, Greenberg later told me, we could get ourselves into trouble: “Because we’re always going to be wrong, no matter how virtuous or politic. Even if we believe that our own world view is fundamentally sound, sometimes the other side has a point.”

George Packer, an Atlantic staff writer, has also resisted. He told me that he was dismayed, while participating in a recent Columbia Journalism School panel, when objectivity was referred to as “the O‑word” and no other journalist would defend it. While Packer does not reject the concept of moral clarity entirely, he believes that most things are not black and white. “Moral clarity has a way of blinding us to the nuances and the details that make it harder to make up your mind. But that’s what readers have to confront: that things are difficult, that most issues are hard to make up your mind about.” Packer worries that the next generation of journalists celebrate “the freedom that comes with not having to be objective,” which, he fears, could ultimately mean freeing oneself from “the tyranny of facts, the tyranny of reality.” Objectivity, he notes, is hard work.

The moral clarity standard has met with comparatively little resistance in Canada, though some of our mainstream journalists have finally begun questioning the wisdom of abandoning objectivity. On a recent podcast featuring the veteran broadcaster Steve Paikin, The Hub ’s Sean Speer brought up the tensions between the ethos of objectivity and “a growing expectation, particularly among younger journalists, that their work is in some way an expression of their values.” Had Paikin observed the disconnect himself? “Only every day,” Paikin joked. Indeed, he considered such tensions to be one of the major fault lines of modern journalism. “I think it’s a big problem.”

Harrison Lowman, The Hub ’s managing editor and a former producer of my podcast, subsequently published a piece criticizing the anti-objectivity ethos in journalism schools — a trend, he argued, that paves the way for bias. These schools are “not raising left-wing partisans, or telling them to support left-wing political parties,” he noted. Instead, they are “developing and encouraging almost exclusively left-wing storytellers, who are most comfortable with progressive storylines.” In the end, he wondered, isn’t that almost as bad for democracy?

To appreciate how objectivity debates impact the trust spiral, journalists must put ourselves in the public’s shoes — and think about what ordinary people say when they hear that many of us no longer believe objectivity is an aim worth pursuing. At a recent Trust Talks panel discussion in Toronto, the CBC’s Nahlah Ayed did just that, speaking with three media bosses, from the CBC, Global, and the Toronto Star. “There are some real debates in newsrooms [regarding] what role the word ‘objectivity’ has, if any, in the work that we do,” Ayed said. “Can you speak to how that, when it spills out into general public discussion, also has a role in undermining, or perhaps boosting, trust?” The responses proved unsatisfying.

But we don’t really need media bosses to answer Ayed’s question for us, because the public is answering it every day. Just give us the facts, they tell us, again and again. In tweets, in online comment sections, in emails and letters to the editor, in ombudsman complaints, the Canadian public asks us, over and over, to deliver straight news. Audiences would like us, to the best of our ability, to gather the facts and a range of perspectives and to trust Canadians to make up their own minds about what it all means. Indeed, reporting from Blacklock’s noted that a recent poll commissioned by the Privy Council found “a large number believed news had become more opinion-oriented and sensationalized in recent years” and that “it was thought that almost every outlet now appeared to have its own perspective and as such it could be difficult at times to determine what the truth of a story was.”

Intramural debates over objectivity flatly ignore the public interest. And by that I mean what the public believes is in its best interest. The thirst for straight facts has been confirmed by anecdotal accounts, by copious amounts of online feedback, by government polls, and by extensive research from the Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism. Its report The Relevance of Impartial News in a Polarised World, from 2021, demonstrates that audiences place a high value on impartiality, despite the complexity of the concept of objectivity. Most people want to be exposed to a wide range of perspectives and are more concerned about suppressing speech than they are about the risks of giving airtime to extreme views. All told, the study found “detailed evidence that impartiality — along with accuracy — remains a bedrock of trust in the news media.”

Ultimately, it is the media’s lack of accuracy that should concern Canadian journalists most when thinking through the spiral of lost public trust.

A failure to acknowledge mistakes. In late November 2022, thousands gathered at Roy Thomson Hall, in Toronto, to watch four prominent journalists spar at the prestigious Munk Debates. The resolution: “Don’t trust mainstream media.” Because the semi-annual event holds an audience vote at the beginning and at the end of the evening, attendees that night had the rare experience of watching public trust in the media erode in real time. It was an astonishing spectacle, with Matt Taibbi and the British journalist Douglas Murray roundly defeating the New York Times columnist Michelle Goldberg and the New Yorker writer Malcolm Gladwell.

From where I was sitting that night, the debate was won when Taibbi laid out, in his opening argument for the resolution, his theory of what has gone wrong. The news veteran grew up in a family of journalists, but he now mourns for the press, because it has destroyed itself “by getting away from its basic function, which is just to tell us what’s happening.” He continued:

My father had a saying: “The story’s the boss.” In the American context, this means that if the facts tell you the Republicans were the villains in a political disaster, then you write it that way. If the facts point more to the Democrats, you write that. If they’re both culpable, as was often the case for me when I investigated Wall Street for almost ten years after the 2008 crash, you write the story that way. We’re not supposed to thumb the scale. Our job is just to call things as we see them and leave the rest up to you. But we don’t do that now. The story is no longer the boss. Instead, we sell narrative, in a dysfunctional new business model.

Taibbi explained that most audiences of mainstream media outlets, whether on the left or on the right, are now politically homogeneous. And “this bifurcated system” is “fundamentally untrustworthy,” because it involves selecting which facts to highlight “based on considerations other than truth or newsworthiness.” The result is not journalism but rather political entertainment — and thus unreliable.

“With editors now more concerned with retaining audience than getting things right,” Taibbi went on, traditional practices have been thrown out. Silent edits have become common, as have anonymous sources. Serious accusations are now levelled without calling subjects for comment. In the Trump era, “an extraordinary number of ‘bombshells’ went sideways,” including multiple allegations made in the 2016 Steele dossier and repeated in the press. “A good journalist should always be ashamed of error,” Taibbi said, “and it bothers me to see so many of my colleagues not ashamed.”

James Bennet made a similar point in his 1843 essay about the Tom Cotton affair: “The Times was slow to break it to its readers that there was less to Trump’s ties to Russia than they were hoping, and more to Hunter Biden’s laptop, that Trump might be right that covid came from a Chinese lab, that masks were not always effective against the virus, that shutting down schools for many months was a bad idea.” These same mistakes were, of course, reproduced here in Canada, though there has been almost no introspection. The CBC’s Brodie Fenlon even admitted as much at the Trust Talks event: “We’re not actually — and I’ll put myself at the front of the line — we’re not very good when questioned ourselves.”

The fact that we lack self-reflection does not stop the public from demanding it of us. The complaints I see most regularly centre on trends in pandemic coverage, specifically on a lack of proportionality, a negativity bias, a deliberate omission of dissenting voices, and an unwillingness to acknowledge errors. From the moment that the pandemic was first declared, as the former CBC Ideas documentarian David Cayley wrote in the Literary Review of Canada in 2020, “newspapers excluded all other subjects from their pages for weeks on end — as if it were almost indecent to speak of anything else. CBC Radio, with a few exceptions, followed suit. Soon, the pandemic filled the sky.” Was this tsunami of coverage proportional? Or did it instead drum up unhealthy levels of fear, in both the media and the public? Is anyone in leadership going to look back at our coverage and assess it?

“Media reporting on COVID has been replete with doom, gloom and hysteria,” the physicians Martha Fulford, J. Edward Les, and Pooya Kazemi pointed out in the National Post in 2022. They cited a report from the National Bureau of Economic Research that showed that in major American media outlets, 91 percent of pandemic stories were negative in tone, as compared with 65 percent of stories in science journals and 54 percent of articles in major media outside the U.S. “Exaggerating the risks of COVID‑19 is harmful,” the group courageously warned, “given the profound negative consequences for children, parents and society. It engenders a perpetual and paralyzing cycle of anxiety and fear, with many unable to return to normalcy.”

I asked Kazemi about that column and others on a recent Zoom call. “There was quite a discrepancy between what I was reading in the medical literature, as well as what was happening in various jurisdictions, especially in Europe, versus what was happening in the North American context and what was being reported in the media,” he recalled. He and his colleagues wanted to urge journalists to consult a wider range of experts and present differing views. “The media was basically feeding one narrative to the population,” Kazemi said. “It allowed the policy makers to push really bad policies without scrutiny.”

It is this lack of dissenting voices that, in my experience, most rankles the public. It’s a criticism that applies to the biggest stories of the pandemic era, including lockdowns, school closures, and vaccine mandates: all unprecedented public policies that had massive impacts on people’s daily lives, finances, health, and well-being. Dissenting voices certainly existed, from the population health expert John Ioannidis of the Stanford School of Medicine to the epidemiologist Knut Wittkowski. “Such opinions — contrary to the headline news — were easily available to those who sought them out, but they made little dent in the emerging consensus,” Cayley observed in these pages four years ago.

The former New York Times columnist Joe Nocera and the Vanity Fair contributing editor Bethany McLean have written that “the weight of the evidence seems to be with those who say that lockdowns did not save many lives,” counting some fifty studies that come to the same conclusion. Mark Woolhouse, an esteemed British epidemiologist, has also told me the lockdowns were not proportionate, sustainable, or effective. Considering the efficacy of lockdowns, or lack thereof, a more robust public debate throughout the pandemic would have been profoundly useful.

Despite the muted warnings of dissenting experts in medicine and public health, school closures were allowed to roll out with almost no mainstream media scrutiny. And as ProPublica’s Alec MacGillis correctly anticipated, these closures were especially devastating for marginalized youth. The New York Times has now reported that “the more time students spent in remote learning, the further they fell behind,” and “extended closures did little to stop the spread of Covid.” Similarly, in a recent presentation for the BC Centre for Disease Control, the medical microbiologist Jennifer Grant, who worked with the province’s ministry of health on COVID‑19 therapy, led colleagues through the large body of evidence detailing the harms to youth, notably in education and mental health and, especially, among vulnerable students. The title of her talk was “Why BC Should Commit to Never Closing Schools.” Yet too few legacy media organizations have admitted they were wrong in uncritically accepting extended closures.

Vaccine mandates also occurred without much scrutiny, and probably the biggest media error in recent years involved the Freedom Convoy that protested against them in 2022. Before the truckers even arrived in Ottawa, Gary Mason at the Globe and Mail declared that it was “clear” the demonstration had been “hijacked by a fringe element that sounds an awful lot like the ‘freedom fighters’ and ‘patriots’ who gathered at the U.S. Capitol building on Jan. 6, 2021, and ended up storming the premises in a poorly organized coup d’état.” On Twitter, the Toronto Star columnist Bruce Arthur described the protesters as “a homegrown hate farm.” A former CBC host in Ottawa referred to the truckers as a “feral mob.” Ultimately, however, the Public Order Emergency Commission told a different story.

I asked the Lakehead University professor and constitutional law expert Ryan Alford, who had standing at the commission, about the disconnect. He observed that members of law enforcement, who were running intelligence operations on the ground, testified “how this was not being driven by those ideologically motivated violent extremists who, if they existed, had only the most tangential connection to what was going on, particularly in Ottawa.” In his POEC report, Justice Paul Rouleau wrote that while the truckers may have been spreaders of misinformation, they were also victims of it — at the hands of a media that amplified a small extremist element. But even after Rouleau tabled his findings, the narrative lived on. In Doppelganger, for example, Canada’s most famous journalist, Naomi Klein, paints the truckers as dangerous extremists. “Many convoy supporters attempted to portray the obviously racist elements as isolated,” she writes in her best-selling book, but “the connections run deep.”

A failure to insulate media from power. At this extreme moment in history — rife with all the challenges I have detailed — the federal government, arguably at the behest of powerful lobbyists for the News Media Canada trade organization, was busy attempting to save Canadian journalism. Ottawa’s subsidies, which included a $595-million bailout, were meant to be temporary but have since been extended and expanded. So far, they have failed to stem cutbacks and closures. As Blacklock’s Reporter noted in a recent brief to the Standing Committee on Canadian Heritage, the Winnipeg Free Press took $822,000 in annual payroll rebates before shuttering its Parliament Hill bureau in 2023; the Toronto Star qualified for $6 million in annual rebates but nevertheless closed its Vancouver office in 2023 and cut 600 Metroland Media jobs. Most recently, the SaltWire newspaper chain in Atlantic Canada, which accepted subsidies, filed for creditor protection.

Not only have the subsidies failed to stem outlet closures and cuts, Blacklock’s has reported, they’ve also negatively impacted the media’s relationship with the public. In its polling weeks before newsroom payroll rebates were increased, the Privy Council found the public opposed the media bailout. Few respondents agreed that supporting the Canadian news industry should be a priority.

A segment of the public now regularly espouses the idea that the Canadian media is a “mouthpiece for the PMO,” an accusation that Lana Payne, national president of Unifor, has said her members in the media now face. It’s a criticism all too familiar to many journalists. “The first thing any idiot on Twitter says is, ‘Oh, I guess you’re waiting for your paycheque from the government,’ ” the Globe and Mail columnist Andrew Coyne recently told me. “Now obviously, that’s loony and cheap. But it feeds that perception — and to some extent it’s a reality.”Marc Edge, a media columnist for Canadian Dimension, agreed: “I think a lot of people look at [the subsidies] and see the press as being on the payroll of the federal government. I don’t think that’s quite true. I don’t think most journalists consider themselves to be on the payroll of the federal government. But this is a public perception. And, in many cases, perception is reality.”

Journalism derives its credibility from its independence. Failing to insulate ourselves from the power that we are supposed to hold to account was always going to be a terrible idea — but it’s an especially terrible idea right now. Certainly the public seems to think so: an Angus Reid poll in July 2023 found that a majority of Canadians — 59 percent — opposed the government funding private newsrooms.

Trading objectivity for activism left us open to ideological capture. It stifled critical thinking. It paved the way for mistakes, which lost us both audiences and trust. It has also put us in a position of taking government money — when it is very much against our interests to do so. And the upcoming U.S. election, replete with a full‑on Trump panic here and elsewhere, threatens to kick off yet another downward trust spiral for our press. Journalists face a choice: Do we do what we’ve done for the past eight years and continue the failed experiment of press activism — hemorrhaging trust, audience numbers, and revenue — or do we correct course and get back to the basics, most especially the aim of objectivity?

A fork in the road. The end of 2023 saw On the Media make its own decision on this front, when it circled back to the questions raised on that fateful morning in 2016. Donald Trump was up in the polls again, and the public radio show finally had to concede that he wasn’t going away.

The same couldn’t be said for Bob Garfield, who’d been fired in the great media purges. His de facto boss, Brooke Gladstone, had announced his departure on the air in 2021: “Bob Garfield is out this week, and as many of you know by now — every week, having been fired after a warning and other efforts at amelioration for a pattern of bullying behavior. The entire staff agreed with that decision.” (Garfield later wrote on Substack that one incident involved him telling a producer that he was “sick and tired of being told how woke I am not.”)

Despite all that had changed at On the Media, the central question about the former president had not. “He has never paid a price for his bare-faced lies,” Gladstone declared on its year-end program. “He challenges journalistic conventions of polite interrogation with pyrotechnical defiance. But to such an irreconcilable electorate, how should the media cover Trump in 2024?” Suggestions from guests on the program constituted a buffet of the same old solutions, including being less squeamish about using words like “fascism” to describe Trump’s political movement and working harder to stress the colossal stakes of the 2024 election to listeners.

While the sky was yet again falling at On the Media, some cooler heads were prevailing elsewhere. Consider a forum at Stony Brook University’s School of Communication and Journalism in New York State. Hosted by the SBU professor Musa al‑Gharbi, it brought together the Vox co-founder Matt Yglesias, the New York Times opinion writer Jane Coaston, and James Bennet to talk through strategies for the coming year. Yglesias, in particular, focused on turning the temperature down on Trump alarmism and scaling back on disproportionate volumes of coverage, which, as al‑Gharbi pointed out, had already surpassed coverage of any other president in history. (Excluding “and,” “but,” “the,” and other non-substantive terms, “Trump” was the fourth most used word in the Times in 2018, spanning all sections, from sports to fashion.) Trump’s four years in office had felt extremely eventful to those covering him, Yglesias reflected, “but there actually wasn’t an incredible amount of enduring policy change.” The best way to handle Trump’s excesses, he maintained, was by calmly and painstakingly interrogating them: in other words, by doing journalism.

As for the trust question, Yglesias acknowledged that those who don’t trust the media basically have an accurate perception of legacy institutions, such as CNN and the Gray Lady — which is that most staffers are on the left. The people who cover politics at mainstream organizations, he continued, tend to be careful, in order to maintain professional relationships. But the people who cover, say, entertainment, feel free to indulge. “I got to a point, though, working at larger places, where I was constantly being annoyed by random asides that were occurring in articles that weren’t really political,” Yglesias said. “I was like, ‘Don’t you guys see? It just discredits us if our review of a Marvel movie is just, in the third paragraph, ‘also Donald Trump is bad.’ ” Nobody reads something like that and changes their vote, he said. Instead, they think, “This is not a publication whose output I need to take seriously.”

News managers were increasingly contemplating that very problem, he said.

The future of news. Despite the dilemmas and dire straits described here, you may be surprised that I am optimistic. This is because, however complex and multi-faceted our problem, the takeaway is actually quite simple.

If we want to restore trust, we need to take the public’s concerns seriously. We do this by interpreting the call for objectivity not as a misguided demand for the sort of purism that’s obviously not possible but as an appeal for a guiding ethos of public service — and for an orientation toward curiosity, humility, fairness, and thoroughness, coupled with a sincere and sustained attempt to remain politically neutral. It’s an approach that Dean Baquet, former executive editor of the New York Times, once described as showing up with an empty notebook and being open to whatever you might hear. This attitude, to quote Baquet’s old boss A. G. Sulzberger, “requires journalists to be willing to exonerate someone deemed a villain or interrogate someone regarded as a hero.”

Practically speaking, journalists must expose ourselves — and our audiences — to more viewpoint diversity and recognize that most people are not as exercised about politics as we in the media are. “The fact is that when Donald Trump was elected in November of 2016, it was such a shock to the system,” the media critic Steve Krakauer recently told me. “There is this existential threat that they were fighting against to save democracy. . . . Most of the people that I encounter here in Dallas, in Texas, who are not overly political — maybe lean left, maybe lean right — they are not thinking about the world during those years in the same way that the media did.”

In his book Uncovered: How the Media Got Cozy with Power, Abandoned Its Principles, and Lost the People, Krakauer, a former executive at CNN and the current executive producer of The Megyn Kelly Show, outlined a number of thoughtful recommendations for helping us reconnect with the public, including allowing reporters to work remotely from smaller communities across the country, hiring more public editors, and reducing the education requirements to enter the profession — effectively opening up the talent pool to a wider range of experiences and perspectives.

Admittedly, a workable twenty-first-century business model might be more elusive, but the answer to our trust problem is right in front of us: we must get back to serving the public. This is what democracy, in fact, is all about. If we believe in democracy, we must believe in the public. What the public is telling us boils down to this: Stop taking money from the government. Stop indulging in moral panics. Stop ignoring dissenting views. Stop letting your personal politics blind you to the facts, making you vulnerable to mistakes. Stop refusing to acknowledge mistakes when you do make them. Stop inserting your views into the news.

I’m convinced that the survival of our industry depends on our ability to hear our fellow citizens. I, for one, will choose to listen.

Tara Henley is a current affairs journalist, podcast host, and the author of Lean Out: A Meditation on the Madness of Modern Life.

Related Letters and Responses

@markfproudman via X

@L_St_Laurent via X

@MrOttawaSlim via X

Dean Beeby Ottawa

Evan Bedford Red Deer, Alberta