Four years ago, the writer and filmmaker Alex Pugsley published Aubrey McKee, the first of five planned autobiographical novels. Aubrey narrates his life in Halifax between 1963 and 1985. The history of the “saltwater city, a place of silted genius, sudden women, figures floating in all waters” confronts him as he passes “through streetscapes where stone townhouses neighbour lofty office developments, a tattoo parlour abuts a low-rise union for longshoremen, and ironstone warehouses preside over grimy wooden piers.” As a teenager becoming a young man, he immerses himself in comic books, bears witness to second-wave feminism, and spends time as a drug dealer, punk rock guitarist, and capable tennis player. Aubrey changes with the cultural and coastal winds of his hometown and its residents. “Whatever these recollections have been,” he says near the end of the coming-of-age tale, “they have been mine, for this was Halifax as I knew it, as I lived it and felt it.”

Pugsley’s characters are drawn from a diverse cast of the misunderstood, the progressive, and the bizarre. There’s Howard Fudge, with “his own kinds of folly and truth and instincts and humour.” Aubrey describes Fudge’s friends as a “cartoon fraternity” of tough kids “from an alternate Halifax, a Halifax outside the scheme of the city as I knew it.” There’s also Karin Friday, the lead singer of Aubrey’s band, the Changelings, who is somewhat embarrassed by her “abundant blonde bangs” because she “did not wish to be regarded as an object of beauty.” The most notable and fascinating character, however, is Cyrus Mair, a “whiz kid, scamp, mutant, contrarian pipsqueak, philosopher prince, pretender fink, boy vertiginous”— and Aubrey’s dearest friend. Pugsley invests these individuals with a familiar, sometimes tragic relatability that nonetheless preserves their outsider mystique.

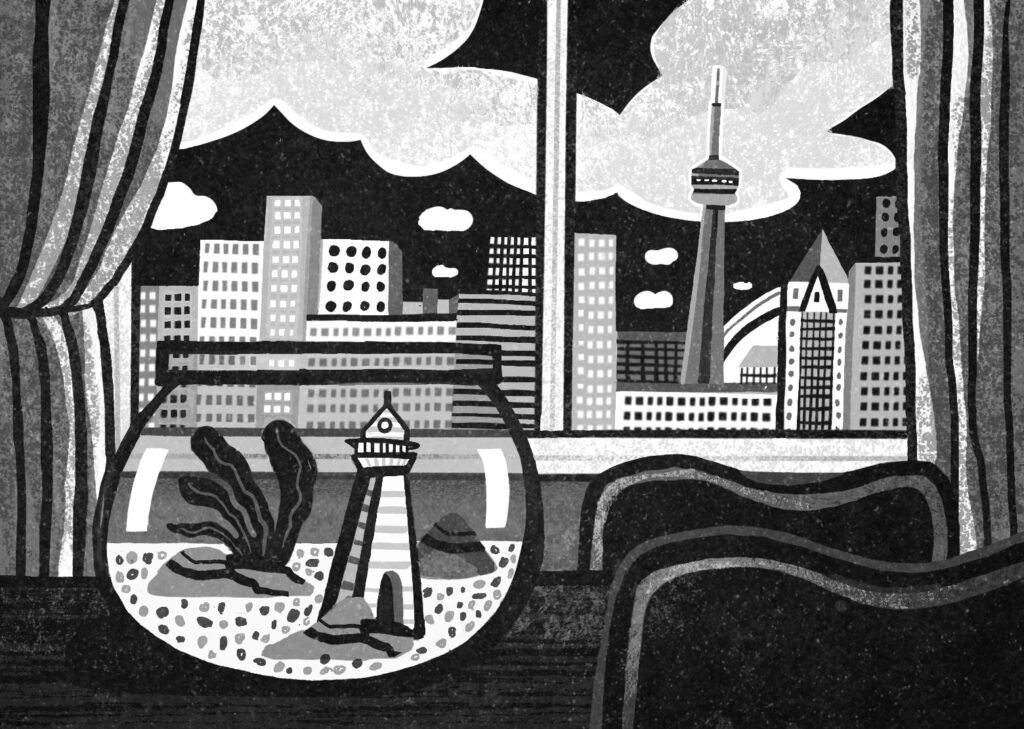

Acts 1 and 2 of a sweeping personal drama.

Sandi Falconer

Aubrey himself emerges as a sort of melting pot of everyone he knows. He feels divided, stretched between too many identities — an internal conflict that he attributes, in part, to his estranged parents. Several passages on the burgeoning divorce rates of the 1970s are among the book’s finest. “What happened to my parents’ marriage was happening everywhere,” Aubrey recalls. “After reporting to a bearded child psychiatrist who asked rather over-placidly which parent I wanted to live with — and me not being able to answer — I lapsed into a surly, uncomprehending funk.” This funk colours Aubrey’s formative years and is amplified when his mom and dad separate for a second time. Instead of revelling in it, he finds his “unsupervised freedom distantly oppressive” and tries to reassure himself that his life “is only somewhat suspended and that moments of fulfillment and euphoria are still possible.”

Aubrey remains emotionally suspended at the novel’s end, even as he prepares to leave Nova Scotia following the death of Cyrus: “I was made to realize that my friend’s time and possibilities, and all those he imagined for us, had ended.” Taking stock of his life so far, Aubrey explains, “I do think of Halifax vast and big, rich and strange, changeless and changing, this mess of small eternities, and in my mind I’ve counted all the cracks in its sidewalks, seen all the tennis balls on its school rooftops, looked in the eye all its leading lights. But in its complexities of course I have moved only a very small part.”

The Education of Aubrey McKee unfolds in a different time and place than the first book, with Aubrey navigating the skyscrapers, fringe theatres, and uncertainties of Toronto during the ’80s and ’90s. Here he encounters another scene full of telling juxtapositions: “People were leaving. Streets were changing. Neighbourhoods were gentrifying. Toronto was a city emerging from a continental recession. On College Street, an Italian shoe store became an upscale organic grocery. The Portuguese laundry, with its paint-peeling Coin Lavandaria sign, became a martini bar called Bar Ultra. And that nameless place with all the second-hand sewing machines in the front window, that became a Baby Gap.”

Now a writer on the comedy series The Calvin Dover Show, Aubrey attends poetry readings, the SummerWorks Festival, and the MuchMusic Video Awards, where he walks the red carpet. As he deploys settings that will be familiar to many readers — Le Sélect Bistro, the 501 streetcar, Kensington Market — Pugsley effectively contrasts the intimacies of Halifax with the artifice of Toronto’s creative scene, where “the idea of a friend is sort of tactical. It’s about how you can use someone to advance your career.” Aubrey confesses that he’s an East Coast fish out of salt water.

Aubrey’s personal relationships often exacerbate the challenges of living in Toronto. Pugsley’s latest characters are as intriguing as his first batch, and he endows them with humour, creativity, and hints of mischief. His talented boss Calvin Dover, for example, possesses a “lunatic brightness” that reminds Aubrey of his late friend Cyrus. The poet Gudrun Peel metamorphoses “from scrappy grad student to glossy national celebrity” while Aubrey falls madly in love with her. Some long-lost acquaintances from Nova Scotia materialize as well, including the playwright and painter Sebastian Hickey, who can be “snobby and cruel,” and Sebastian’s intelligent brother, Dalton, who is “never warm or generous or encouraging” unless Gudrun or other women are nearby.

The persistent funk of Aubrey’s formative years re-emerges during his decade-long relationship with Gudrun, which is equal parts love and heartache — the throes of passion inevitably followed by insecurities and disorder. Recalling a fight during which Gudrun threw plates at his head, Aubrey says, “I began to understand I was being defined by some severe dysfunction, that I’d become involved with a very troubled person, and I wondered if I was giving myself over to something that would sooner or later destroy me.” Personal conflict, it seems, will follow Aubrey wherever he ventures — no matter how “smart, tart, and luminous” the company.

Although Aubrey loves Gudrun, he describes their time together as one of “emotional schizophrenia,” full of feelings that are “vexed, confused, disordered.” As it was in the earlier book, Pugsley’s writing — with declarative prose and stylistic confidence — is consistently poignant in The Education of Aubrey McKee.

While the second book builds upon the themes and tone of the first, it is nonetheless imaginatively original. Indeed, Pugsley concludes the novel not with first-person narration but with a poem, by Gudrun, and a three-act play, by Aubrey. With insightful, tormented fragments, the speaker of the poem echoes many of Aubrey’s thoughts, even using some of his words:

and me a girl playing at poems

vexed in texts and haruspex

fulgurating in some desperate canton

so you followed me down one-way streets

The play, A Night with Quincy Tynes, takes the form of an extended conversation between Aubrey, forty-three, and a slightly older man from Nova Scotia who makes a brief appearance in Aubrey McKee: “Many years later, Quincy Tynes will re-enter my biography at a crucial juncture, saving my life in another city, but when I am thirteen I am mostly terrified of him.” They talk about music and basketball, about sobriety and alcoholism, and especially about relationships. “Sometimes these things are about a connection,” Aubrey tells his friend, who responds, “Says the man who has gone out with the most dysfunctional, fucked-up women on the planet.”

Whether it’s prose, poetry, or drama, Pugsley’s writing is a force to be reckoned with. He does not shy away from illuminating the dark aspects of life that many would sooner repress than indulge. Readers willing to confront the deep-seated moments that build character may extract something sublime from Pugsley’s work of intense self-discovery. Along the way, they may find themselves lost in their own memories, revisiting joys and sorrows that are familiar yet bewildering. Bold and dynamic, Pugsley’s novels are lively and vivid, filled with individuals who are benevolent and cruel and with scenes that are captivating and terrifying. Aubrey McKee and The Education of Aubrey McKee are the first two acts of a sweeping personal drama, and any remaining volumes cannot come fast enough.

Liam Rockall studies English literature at Western University.