In 1938, the Jewish architect Victor Gruen left Nazi-occupied Vienna for New York. When he relocated to Los Angeles a few years later, he was taken aback by the impersonality of the city’s shopping scene. Across Europe, commerce was a communal activity, an opportunity to walk the high streets, admire elegant storefronts, mill about, and perhaps meet new people. In Southern California, consumers drove to their destination, picked up their stuff, and drove home. Gruen set out to change such behaviour by uniting disparate retailers in a single structure built around walkways. These “shopping centres” would be a “restful, even life-affirming” tool to vitalize a lonely activity and restore a sense of community to fractured urban design. His brainchild — the first fully enclosed, climate-controlled mall — would open halfway across the country in 1956, just outside of Minneapolis. The Southdale Center, in the suburb of Edina, continues operating nearly sixty-eight years later.

On many counts, Gruen’s endeavour was a phenomenal success. Some 40,000 visitors attended Southdale’s grand opening, and in the ensuing decade, developers built more than 250 shopping centres throughout the United States. But Gruen’s broader vision never came to pass. Malls didn’t help bring people together; they deepened isolation even more. Why? The construction of malls caused the value of surrounding land to skyrocket. Savvy investors bought up that property and sold it to make way for houses — not the vital if less profitable community pillars such as dental clinics, post offices, and schools that Gruen had envisioned. Shortly before he died in 1980, he disowned his invention as a “bastard development” that had “destroyed our cities.” Like another famous (albeit fictional) Victor, he vigorously repudiated his own creation.

A writerly defence and celebration of the shopping mall.

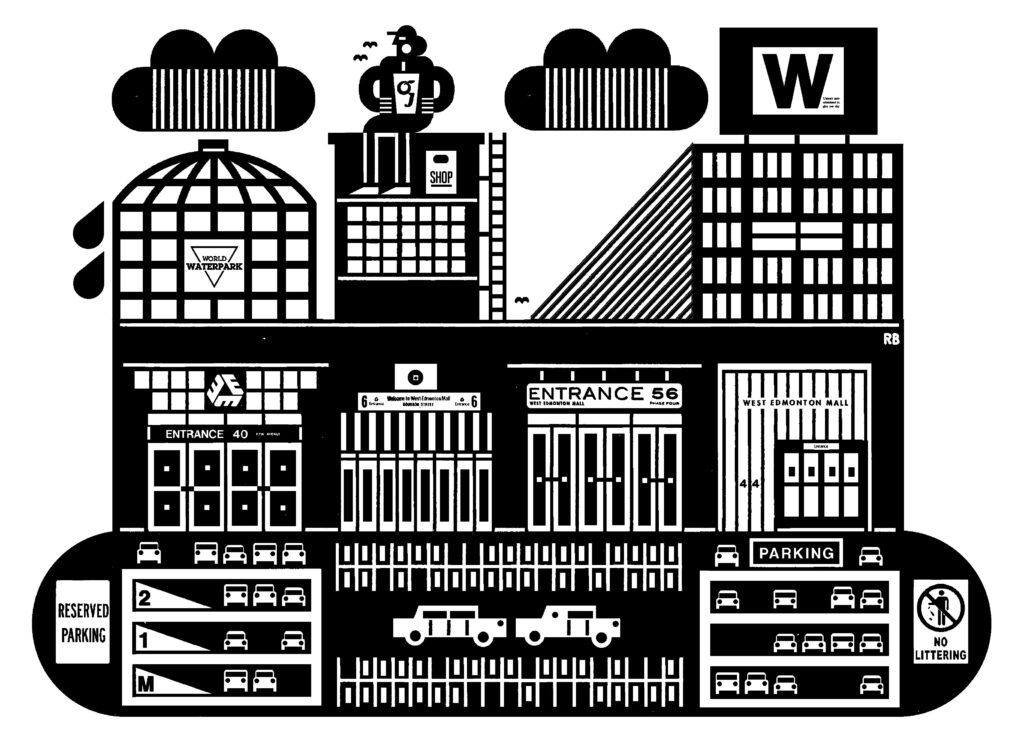

Raymond Biesinger

Gruen would probably be happy that — at least by many accounts, including Rinny Gremaud’s All the World’s a Mall, originally published in French but recently translated into English by the University of Ottawa’s Luise von Flotow — shopping centres are inching toward extinction. Kate Black, however, disagrees with that prevailing assessment. In Big Mall: Shopping for Meaning, the essayist and fiction writer observes that, “judging by American think pieces alone, you’d be led to believe that malls — all of them, everywhere — are dying.” But she contends that rumours of their demise are greatly exaggerated. Across the United States, mall blight has principally affected smaller locations, particularly those anchored by failing department stores like JCPenney and Sears. These account for around a quarter of the country’s thousand shopping centres. All over America and elsewhere, bigger malls are doing better than ever because they have “transcended merely functioning as a place to buy things.” Many have become “massive spectacles” that can include libraries, movie theatres, roller coasters, and zoos, among other amusements. In some places, malls even serve as vital places of respite. Throughout Asia and the Middle East, Black reports, “the mall is a shelter, rising to meet the needs of an increasingly unbearable climate.”

Today Black lives in Vancouver, but she grew up in Alberta, about twenty kilometres north of a particularly notable shopping centre: West Edmonton Mall. When it opened in 1981, the 1.1-million-square-foot behemoth was the biggest in the world. Now nearly five times its original size, West Edmonton Mall remains the largest in Canada — a gargantuan structure that “rises like a spray of brutalist mountains from Anthony Henday Drive.” (With some twenty-one million square feet, Tehran’s Iran Mall has held the world title since 2018.) Inside, visitors will find 800 stores, 100 restaurants, a Crunch fitness club, two hotels, North America’s largest indoor amusement park, and the world’s largest indoor wave pool. Outside, they’ll find the world’s largest parking lot, with some 20,000 spaces. On busy days, some 100,000 guests pass through the building’s doors. With descriptive prose, Black captures the place’s sheer immensity: “You can’t get a photo that captures its size. It’s an amorphous puzzle of material, defying faithful description, facing inwardly on itself, shy.”

Although it touches on history, philosophy, and statistics, Big Mall is essentially autobiographical. Black explores West Edmonton Mall and the mall as a concept through the prism of her personal experiences, including her first panic attack — as a teenager at the food court A&W. Her tone is generally lighthearted but at times earnest. She laments that today’s young mallgoers are “never not texting or TikTokking or whatever it is now,” and she pokes fun at those Albertans who arrive with “metal testicles on their trucks.” The book is well written but sometimes heavy on jargon. Black describes the mall of her childhood, for instance, as a “space of agency during the frustration of that liminal time.”

Black is at her best when she grounds her reflections in more straightforward prose. One memorable account is of the Mindbender accident of 1986, when the rear car of the mall’s roller coaster derailed, killing three passengers and seriously injuring a fourth. Black is fascinated with the tragedy because it could easily have happened to her on that fateful day; writing in the second person, she describes the derailment as “the event that could have vaporized your existence, or the possibility of your future existence, all in an unlucky instant.” Elsewhere, Black details her former “dolphin obsession”: as a young girl, she would watch the regular performances of the mall’s resident cetaceans, Howard, Mavis, Maria, and Gary. Only later did she become aware that they had been kidnapped off the Florida coast and that advocacy groups had been lobbying for their release for years. Today it’s not unusual to see an African penguin dawdling among shoppers’ feet. In fact, a dozen or so of the flightless birds live in the mall’s underground aquarium. Occasionally their keepers let them out, one at a time.

Black’s abstract theoretical detours are less compelling. “If we define neo-liberalism as the ideology of people’s entire lives taking place in the marketplace,” she argues, “the mall makes for a pretty perfect metaphor.” (Most of the malls I know close at 9 p.m. — or 6 p.m. on Sundays. There’s a lot of life taking place elsewhere.) She forecasts a “coming social and environmental collapse” but finds solace in the fact that our impending doom “means that things won’t be this way forever.” (She seems to take for granted that whatever comes next will somehow be better.) Black also maintains that for young people, the mall contains “liberating elements,” because it’s a place where they can “aesthetically depart” from the values of their parents and teachers. (These departures actually strengthen dominant economic modes, however, since they reinforce the supposed fair-mindedness of the overarching system that allows for the possibility of such consumerist deviations in the first place. Hardly liberating.)

Yet Black does offer a lucid critique of utopia as a concept. “If you just look at the potential of the space alone,” she writes, “the mall could be a pretty perfect place: protecting us from the elements, entertaining us, giving us everything we need to make ourselves more beautiful.” Looks can be deceiving, of course. The mall can never reach that “platonic ideal of meeting all our needs and desires.” One obvious reason is that none of us has infinite money, so we can’t afford everything we want at any given time. On a deeper level, it’s because the mall has rules: “Security can look at anyone using the mall incorrectly, call it loitering, and escort them from the utopia.” No place can be ideal if one must conform to some external standard for admission. Inclusion must be unconditional; otherwise, the place is not for everyone and is not properly utopic. “Inevitable dysfunction” is baked into any mall developer’s pie-in-the-sky aspirations: “The dream doesn’t look right when it comes to life.”

Ultimately shopping centres like Southdale and West Edmonton Mall exist to make money. Throughout Big Mall, Black strives to separate that harsh reality from her nostalgia-influenced sense of what the mall could be. In her most pointed observation, she articulates why she, like so many others, is drawn to shopping centres despite the capitalistic imperatives: “The mall gives me the full sensation of life without meaningful interaction with other people. There’s safety in that, in a journey unbound to the unpredictability of others.” Whether you’re actively shopping or not, the mall offers a substitute for organic relationships, with nameless people fulfilling their prescribed social roles. This environment closes the gap between Black’s simultaneous fear of and need for human connection. It collapses what she calls the “friction point” between herself and the world. Restful? Perhaps. Life-affirming? Not exactly.

Alexander Sallas is a doctoral candidate at Western University and an editor-at-large with the Literary Review of Canada.