Toward the end of Corinna Chong’s sophomore novel, Bad Land, six-year-old Jez asks her aunt Regina how the badlands, the region of southern Alberta dominated by towering sandstone hoodoos and sculptural rock face, got its name. Regina’s tentative answer: European explorers — no, Indigenous people — first called it that, and can you blame them? “Imagine,” Regina remarks, “how cruel this land would have seemed to someone who had never known anything like it before.” Jez considers this while looking out of a car window at the arid hills, eventually adding that those people must have changed their minds: “They saw it wasn’t really bad.” The words speak just as much to the landscape as to Jez and her aunt.

Bad Land foregrounds questions of inheritance and redemption, using its setting of Drumheller, Alberta, known for its otherworldly terrain and fossil beds, to explore family ties, destiny, and agency. Set during a sweltering summer in 2016, the book is divided into sections named for the steps in a petrified rock’s formation and discovery —“Layer,” “Press,” “Alter,” and “Expose”— each accompanied by an explanatory note. These references go beyond geological information. They mirror the transformations undergone by Regina and the unearthing of family truths long buried and forgotten.

Regina returns home one day to find two figures waiting for her, surrounded by suitcases. She recognizes her younger brother, Ricky, whom she hasn’t seen in seven years, and his daughter, Jez. They give no reason for their arrival at the old family home, nor do they explain where Carla, Ricky’s wife and Jez’s mother, is. As Ricky settles in, his silence bothers Regina. “Nothing had changed, was what he said without saying,” she tells the reader. “As if he’d never left, we’d never grown beyond childhood, this house had never become mine.”

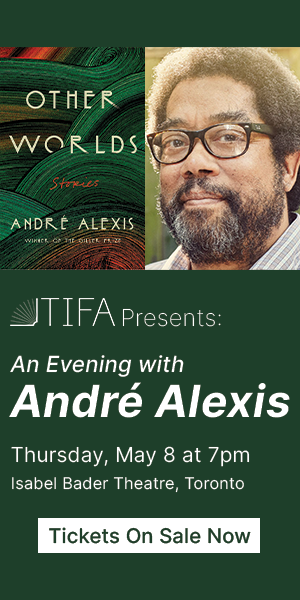

The towering hoodoos of Drumheller.

Jake Warren; Unsplash

While she’s irritated by her brother’s disregard for the passage of time, Regina does seem averse to change herself. Her mother, a lone parent and amateur paleontologist from Germany, brought her to Drumheller as a baby. Now in her thirties, Regina works at the Fossil Land admission booth and still lives in her childhood home. Recent developments in her life consist of an awkward blind date at a bowling alley, the introduction of animatronic dinosaurs at work, and her doctor’s recommendation that she start walking regularly for her health. Ricky and Jez’s appearance, therefore, upends what has been a routine, unexamined, and mundane existence.

Almost immediately, Regina detects that something is off with Jez. After being instructed to hold her aunt’s pet rabbit gently, Jez grabs him violently. Another time, she casually calls Regina a “big ol’ bitch.” At the museum, she bites another visitor. Jez’s behavioural issues have obviously played a role in her and Ricky’s departure from Phoenix, where they live, but we’re left to wonder about the catalyzing incident until halfway through the novel, though there are hints that whatever happened was serious. Most notably, Ricky gets inexplicably upset when his sister takes Jez to a local park frequented by other children.

By the time all is revealed, we’ve also learned about Regina’s past, with its own share of painful moments and cruelties, both accidental and deliberate. She reflects on her childhood and her obsession with fossils, and she wonders “if it wasn’t one of the many reasons I was friendless.” These revelations are doled out judiciously, so that we begin to see her eccentricity and dysfunction in relation to Jez’s problems. The devastating act that brought Ricky and Jez back to Alberta is shocking — she shot a boy through the eye, killing him — but Chong isn’t particularly interested in exploring child psychology or the ramifications of a violent event for a family or community. Instead, the focus is on Regina and how her relatives’ arrival alters her life, with the shooting serving an almost utilitarian purpose in the larger story. It creates intrigue and then it affirms something Regina has already realized: that she and her disturbed niece share a rare kinship. “I recognized now what had always been true,” she says, “that Jez and I belonged to each other, bound by blood. If I were asked to call it by a name, I would call that feeling love.”

Regina reacts to this most troubling of realizations by trying to spirit her niece away from any further disruption, whether that be talking to psychiatrists or a reunion with Carla. Without telling Ricky, Regina and Jez hit the road in the middle of the night. In the second half of Bad Land, the pair journey northwest past raging wildfires. Regina recalls her own childhood as they head to where her estranged mother, Mutti, now lives.

Chong is skilled at writing landscapes — at turns, you feel both the claustrophobia and the sense of freedom evoked by the sprawling badlands — and she has an eye for the odd detail that can vividly anchor a scene. Her use of reliquiae as a metaphor for generational inheritance is also compelling. A fossil “was not the animal’s self but rather an imposter,” Mutti once told young Regina. “A kind of empty shell filled up with minerals to become a perfect imitation of the original.” We may be formed in the shape of our ancestors, the novel suggests, but we aren’t condemned to repeat their mistakes.

Unfortunately, Bad Land sinks under the weight of its ambitions and heavy subject matter, including parental abandonment, mental illness, abuse, body image, gender-based violence, the slippery nature of memory, and social disconnection. Perhaps its disappointments are a matter of incorrect proportion: without more sustained focus on one or two of its themes, the novel feels too slight to handle all that it gestures to. Instead, many plot points create distractions, compensate for thinly drawn characters, and produce a layer of frustrating ambiguity. For instance, Regina feels threatened by a man she encounters at a campsite and strikes him with a large rock. She and Jez leave him without looking back. Does he die, or is he merely injured? The narrative never returns to him, except briefly when Regina admits to herself that she acted in an “unhinged” manner and later when she conjures the image of his “face contorted by fear, the crack of rock on skull.”

In her 2023 short story collection, The Whole Animal, Chong makes productive use of elision, but here so much is left in shadow, including Regina herself, that the overall effect is one of muddy confusion.

Marisa Grizenko is the reviews editor for Event magazine.