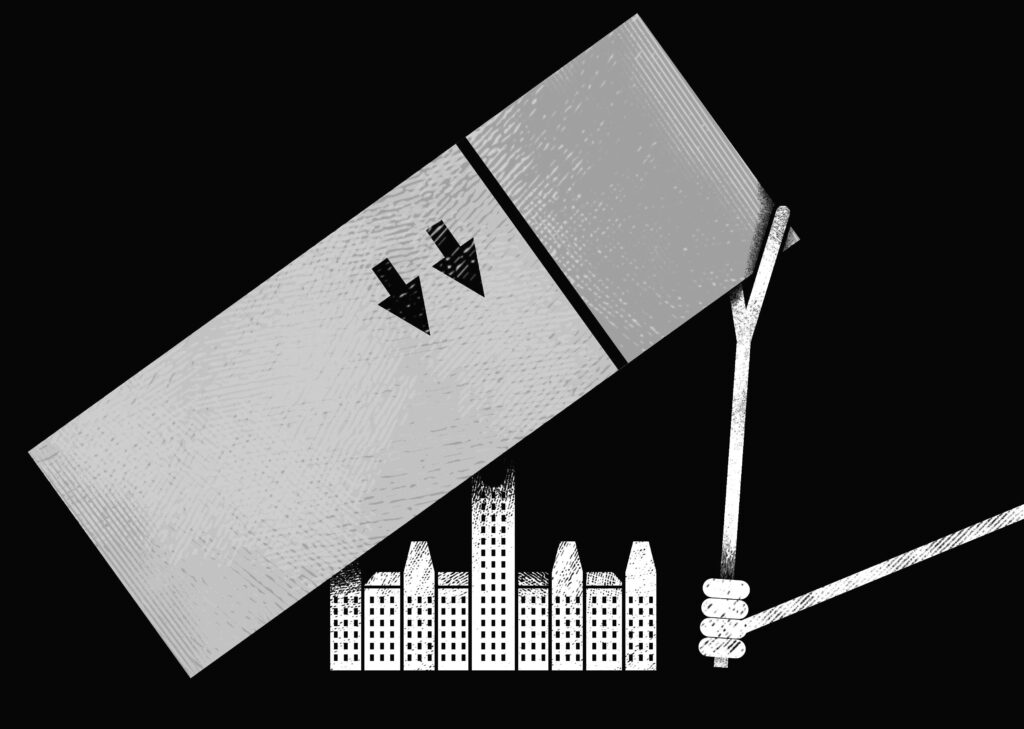

Chris Hurl, a sociologist at Concordia University, and Leah B. Werner, a doctoral candidate in his department, want to see big transnational professional service firms, known as TPSFs, pushed out of government. Their book, The Consulting Trap, is a “citizen’s guide”— verging on a manifesto — that encourages readers to challenge officials to stop hiring these companies. They argue that TPSFs undermine our democracy by setting out “to restructure the state in a manner that hooks governments, fostering growing reliance on their services.” Such firms hard-wire “a policy program built around neoliberal principles inside the state, effectively fostering the establishment of hybrid governance arrangements,” along with austerity and efficiency. TPSFs are “increasingly positioned at the core of public service delivery but with very little accountability or transparency.”

These are large claims. Certainly the huge size of TPSFs suggests they are formidable actors, even relative to government. The elite strategy firms (McKinsey, Boston Consulting Group, and Bain) had a combined 83,000 employees globally in 2022. The so‑called Big Four accounting firms (Deloitte, PwC, EY, and KPMG) had 1.3 million employees, while the top three information technology firms (Accenture, Capgemini, and IBM) had 1.2 million. By comparison, the government of Canada has 368,000 employees. Hurl and Werner report one estimate that consulting services in 2019 totalled $71 billion (U.S.) in the United States and over $4 billion (U.S.) in Canada; others suggest the market is four or five times larger.

The Consulting Trap describes the rise of the three major types of firms, how they cultivate government contracts, and the products they offer, while outlining perceived problems with their ideological bias and lack of transparency. It reports on various scandals as well as on money wasted on poor advice or services, often in the United Kingdom (the authors just briefly mention the collapse of the outsourcing giant Carillion, which cost taxpayers $270 million). No happy stories are included here.

Has Ottawa really been captured by professional service firms?

Matthew Daley

Hurl and Werner are in good company in distrusting TPSFs. In the recent U.K. election, both Labour and the Tories pledged to halve contracts with the big consulting firms. In France, Emmanuel Macron was targeted for his too-close relations with McKinsey, and the Cour des comptes urged the government to rein in its sometimes “inappropriate” use of consultants. In 2015, Justin Trudeau’s Liberals promised to cut back on consultants, though they actually increased their use; undeterred, the 2023 budget promised reductions in professional services, notably management consulting. Pierre Poilievre has also said he’d cut them back if the Conservatives form government.

So TPSFs are not popular. But are they a threat? One of the authors’ first charges is that the Big Four accounting firms “orchestrate tax avoidance for economic elites and transnational corporations” on a massive scale, saving their clients nearly $500 billion a year globally. Tax avoidance is a major issue, but cracking down on it is a perennial cat-and-mouse game. In 2023, the Organisation for Economic Co‑operation and Development announced a “groundbreaking international tax agreement” of 145 countries designed to help prevent tax avoidance and protect against the erosion of tax bases. While we might deplore how accounting firms and lawyers abet such avoidance, it seems unrelated to governments’ use of consultants. The authors do not suggest that accounting firms shape tax policy. Rather, they become experts on the loopholes.

What, then, are the charges against the TPSFs as consultants to government? They carry neo-liberal ideological baggage. They often give bad value for money. Sometimes their behaviour can be egregiously self-serving and even illegal. And they can be too cozy with political friends.

Among Ottawa’s recent high-profile consulting scandals, the worst featured obscure firms, not TPSFs. A small group of these businesses, some with only two employees (and in one case, one of those employees actually had a day job for the Department of National Defence), collectively won over $1 billion in contracts from the federal government over thirteen years. Their mastery of a dysfunctional procurement regime enabled them to secure contracts in areas where they had no direct competence and then to pass the actual work on to subcontractors, while keeping 15 or 30 percent for themselves. The scandal of the ArriveCAN app provided a feast for opposition MPs. The police are investigating.

The favourite political target of critics of TPSFs is probably the elite firm McKinsey. It recruits stars from top universities, many of whom go on to top jobs in industry, and it has impeccable links with government. Its corporate purpose statement shows its strong sense of self-worth, with an ethos of clients’ interests first and the highest professional standards. But the bloom is off the rose. McKinseyites now find their beloved company embroiled in political controversies and the focus of such exposés as When McKinsey Comes to Town, by Michael Forsythe and Walt Bogdanich, and The Firm, by Duff McDonald, which depict an organization engaged in an amoral pursuit of profit, promoting downsizing and offshoring. These books reveal McKinsey’s advice to Purdue Pharma on how to turbocharge opioid sales, the convictions of two of its own top partners for major insider trading, and its role in enabling the Gupta family’s “state capture” in South Africa. (Nonetheless, McKinsey still makes a lot of money, which is more than can be said for the big accounting firm Arthur Andersen, which was destroyed by its actions in the Enron scandal.)

Some journalists and opposition politicians have seen scandal in McKinsey’s contracts with the federal government and supposed links to the prime minister. In July, The Walrus ran a breathless article characterizing the consultants as a “shadow government.” And well over a year ago, Parliament asked the auditor general to do a special investigation, which found frequent disregard for contracting and procurement rules — a problem internal to government — but no evidence of political interference or malfeasance by McKinsey. Moreover, its $200 million in contracts from 2011 to 2023 represented less than 1 percent of federal spending for similar services in that period. Small beer for a scandal.

Of course, we have seen genuine scandals involving TPSFs and the federal government, notably the woeful tale of the Phoenix pay system for civil servants. IBM was awarded $5.7 million, which grew to $393 million, for a system that virtually crashed upon launch, with countless cases of over-, under-, and non-payment. Another $2 billion may be needed to clean up the mess. There has been much blame to share — among consultants and, as the auditor general found, within the government. Ottawa is now engaged in a long-term process aimed at replacing Phoenix, and its first step, inevitably, has been to award a new consulting contract.

Hurl and Werner get closer to detecting a threat to democracy in their discussion of privatization. Although privatization comes in many guises, the authors are focused on public-private partnerships, or PPPs. These can be more expensive for governments than operating projects directly, and having a profit-seeking enterprise deliver a public service can be problematic, at least without adequate accountability and protections. Major issues occurred with the first wave of PPPs in the 1990s, but risk sharing and protections for the governmental role have much improved. One learns little of these developments from Hurl and Werner’s sketchy account of PPPs in Canada, however. They don’t mention the Harper government’s Building Canada Fund or its infrastructure projects worth nearly $9 billion. More surprisingly, there is scant discussion of the Trudeau government’s ambitious $35-billion Canada Infrastructure Bank. Hurl and Werner are right that TPSFs have a major interest in PPPs, as do engineering and law firms, insurance companies, and pension plans. Indeed, the government has staffed the Canada Infrastructure Bank with many TPSF alumni: its chief executive officer came from McKinsey; its chief financial officer and chief investment officer spent time at PwC. Would Hurl and Werner see here a government admirably bringing expert capacity inside — or allowing a neo-liberal takeover of a major initiative? Governments of various political stripes have sponsored some 300 PPPs in this country; a book remains to be written on the experience.

Aside from PPPs, Canada has seen very few privatizations for the direct delivery of government services by professional firms — nothing like the privatization of prisons and some social services that has happened in the U.K. and the U.S. Direct privatizations more often involve small contractors who get cleaning and security service contracts. In March 2023, eyebrows were raised when a Veterans Affairs contract for rehabilitation services worth $570 million went to a health firm owned by Loblaw Companies. But the key role of case officers remained within government, and the private services were largely provided by health professionals, as happens more generally in the sector. In Ontario, Doug Ford’s Progressive Conservative government has been accused of opening the way to more privatization of health care by permitting private clinics to undertake certain procedures. These issues merit careful scrutiny, but they have little to do with TPSFs.

One area where Hurl and Werner believe the ideological bias of TPSFs really shines through is benchmarking. In 2001, for example, Mike Harris’s PC government in Ontario mandated a performance measurement program for municipalities. Municipal staff worked with a consulting firm (subsequently acquired by KPMG) to categorize services: mandatory, essential, traditional, or discretionary. The authors suggest that benchmarking gave the consultants “considerable power in defining norms for service delivery” and made discretionary services vulnerable. While some such risks may have arisen, they also report that when Rob Ford, as mayor of Toronto, proposed cutbacks using the KPMG framework, a majority of city council said no. Politicians have independent judgment and are free to exercise it, and benchmarking is a tool of limited utility.

On balance, Hurl and Werner fail to make the case that TPSFs are a major threat to our democracy. They receive perhaps 1 or 2 percent of the roughly $16 billion Ottawa spends annually on professional and special services — a much larger category than consulting services alone. That’s not chump change, but around 80 percent of consultant money goes to IT contracts, where governments legitimately need outside expertise. There is little evidence that governments turn to TPSFs for public policy advice; rather, consultants sell advice and services that are largely oriented to efficiency and effectiveness. The purchase may be a computer system or a management arrangement. It may be good or bad value.

Hurl and Werner seem to see almost no value, at least for government, in the work of TPSFs — almost as if the huge firms have nothing to offer. But these organizations have developed expertise in specialized areas with the advantages of scale and wide-ranging international comparisons. As for their role in promoting neo-liberalism, this is a baby with many parents. The banks, large companies, think tanks, and economists have all contributed. TPSFs are arguably more the servants than the masters of neo-liberal policies, which are now increasingly questioned. No doubt they would happily seek contracts in a post-neo-liberal world too.

Yes, there are issues with TPSFs, as with contractors more generally. They can be self-interested. They can oversell and underdeliver. They are expensive. They can avoid accountability and be opaque. They can try to hook governments into long-term dependency. Governments very much need better procurement systems and greater staff capacity to handle complex procurement, whether it be for contracts with TPSFs or for fighter jets. Caveat emptor.

George Anderson served as deputy minister for intergovernmental affairs, as well as for natural resources.