Diana, Princess of Wales, believed that “dancing makes you feel heaps better.” But I’m not sure Her Royal Highness would feel that way after reading the book her dancing instructor and friend, Anne Allan, has written about her. It’s not that Dancing with Diana has negative things to say about the princess (it doesn’t), nor is Allan anything but empathetic (she’s non-judgmental to the point of credulousness). It’s just that this is yet another work that proves if you’re a celebrity, the question isn’t whether your acquaintances will exploit your notoriety; it’s simply a matter of when. Diana never learned the lesson, strictly followed by her in‑laws, that it’s best to never complain and never explain — especially to the hired help.

Originally from Glasgow, Allan trained at the Royal Ballet School in London. In 1981, while she was ballet mistress of the London City Ballet, she was asked to be the private dance teacher for Diana. Lessons continued for nine years, with breaks for her pupil to give birth to William and Harry, do royal tours, summer at Balmoral, and so on. Later, Allan directed plays and musicals in Canada and served as artistic director of the Charlottetown Festival for a decade. She now lives in Toronto.

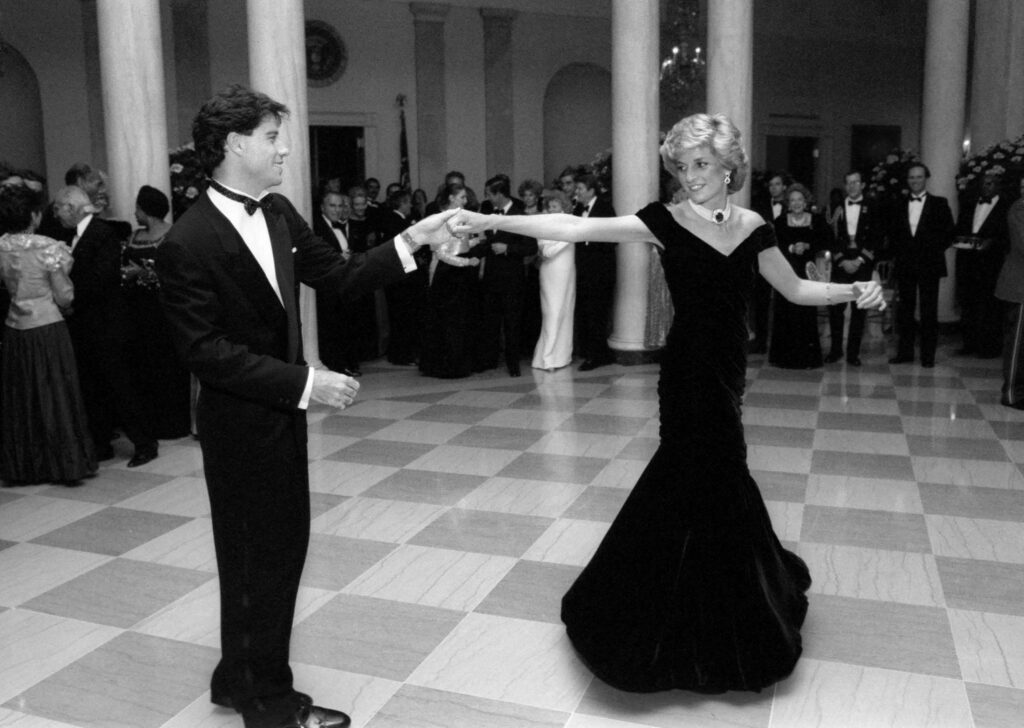

John Travolta dances with the Princess of Wales at the White House, on November 9, 1985.

DPA Picture Alliance; Alamy

Diana has been quite the gravy train for writers. There’s the classic 1992 Andrew Morton biography, Diana: Her True Story, which was written with the princess’s participation as part of her revenge tour against Buckingham Palace and Charles, then Prince of Wales. Morton returned to the trough in 2004 with Diana: In Pursuit of Love. Tina Brown, the former Vanity Fair and New Yorker editor, has done double duty as well, publishing The Diana Chronicles in 2007 and Remembering Diana a decade later. And there’s Diana in Search of Herself: Portrait of a Troubled Princess, by Sally Bedell Smith, who has also dipped into the royal well to produce books about King George VI and his queen consort, Elizabeth, as well as their daughter Queen Elizabeth II and her eldest son.

Some maintain that authors who write about Diana have only been doing their job, just like all those paparazzi who stalked her for photographs. And while the princess may have felt those in the media were her adversaries, she was adept at using them for her own purposes. Recall the post-separation television interview that was adroitly choreographed to stick it to Prince Charles. Remember the brilliantly staged photo ops, the most iconic being of Diana sitting alone in front of that great symbol of spousal devotion the Taj Mahal. Replay in your mind scenes of Diana touching an AIDS patient or her land-mine walk in Angola. Regardless of who was using whom, Diana didn’t have any illusions about reporters and editors. Surely she’d be devastated that the greatest exploitation has come not from them but from those closest to her: friends, lovers, and employees.

Diana’s brother, Charles Spencer, who appeared a tad opportunistic with his attention-grabbing attack eulogy (as it’s been called) at her funeral twenty-seven years ago, made circumspect references to his big sister in The Spencers: A Personal History of an English Family. Brotherly love also prompted him to create the must‑see attraction of her grave at their ancestral estate, Althorp. (One wonders whether the stately home would attract many visitors today without this shrine.) But at least Lord Spencer hasn’t written a tell‑all about his sister.

Leave that sort of thing to Wendy Berry, who published The Housekeeper’s Diary: Charles and Diana before the Breakup, in 1995. Perhaps inspired by Berry’s domestic espionage, Diana’s butler Paul Burrell revealed even more eight years later with A Royal Duty. (He continues to be asked for comments about her and her sons, William and Harry.) In 2002, one of Diana’s bodyguards, Ken Wharfe, collaborated on Diana: Closely Guarded Secret. Not to be left out, Diana’s psychic and alternative healer, Simone Simmons, co-wrote Diana: The Last Word. Over the last five years of her life, the princess had shared a lot of confidential stuff with Simmons, who seems to possess a prodigious memory for juicy material. And just recently, Diana’s long-time hairdresser co-authored It’s All about the Hair: My Decade with Diana, H.R.H. Princess of Wales, a slightly gimmicky “interactive book” about her “timeless influence on fashion, culture, and the hearts of millions.”

If Diana asked her staff to sign non-disclosure agreements, they had little impact. It’s certainly trickier to ask a lover to sign one. Most egregious among that cohort is James Hewitt, with whom Diana had her first extramarital affair. Hewitt’s the cad who kissed and told and told and told, in Love and War and then in Moving On and then again in A Love like No Other: Diana and Me.

In publishing their books, those whom Diana trusted usually suggest they have little interest in cash or fame. They’re just compassionate insiders who want to set the record straight! So it is with Allan. “I have often been bitterly disappointed with interviews regarding the Princess,” she explains in her publisher’s marketing materials. “There was always so much more to this incredible woman than what was depicted.” Allan’s book is intended as a “fresh look at the more personal side of Diana.” And, of course, reading it is supposed to give us “a deeper understanding of just how extraordinary she was.”

Unfortunately, there’s not much new to be learned in this telling. Diana liked to dance, she enjoyed attending the ballet and musicals, and she was interested in artsy types. She was desperately needy for love and reassurance — and indiscriminate about where she sought it. Most writers portray Diana, as Allan does, as a modest, kind, well-mannered aristocrat with a penchant for writing sweet notes at appropriate moments. She had a sense of humour, something many commentators say her ex-husband lacks. She did the things devoted moms do, Allan gushes, as others have gushed before. Diana might have been less saintly and more of a real mom if she had survived that car crash in Paris or had to confront, eventually, an emotional emptiness greater than her own: that of her “spare” son, Harry. We’ll never know, and Allan doesn’t speculate.

Even without major revelations, Dancing with Diana does offer some amusing observations. Allan recalls Diana’s first lesson, when “her underwear was showing below her leotard and tights — what looked like Marks and Spencer knickers were very evident.” (Just imagine one of those iconic couture ball gowns concealing the most egalitarian of underwear!) Allan also remembers how the princess “came bounding into the studio” after she had “confidently danced” with John Travolta at the White House: “I was delighted to see that she had stretched her arms beautifully and lifted her head as she moved.” The prurient or cynical reader waits and waits for Allan to spill something shocking, to be critical or at least skeptical of her idealized student. That doesn’t happen, because this book sits firmly within the Diana Fan Club School of Writing.

Allan begins her story with a “very British upper-class voice” on the phone informing her she’s to teach Diana. Aware she was being considered for this role, Allan knows it’s not a crank call. She doesn’t speculate on why she got the job, though given the longevity and apparent intimacy of her relationship with Diana, she might have asked — at least eventually. That phone call isn’t much to fill a chapter, so we’re presented with a long description of Diana’s wedding, just in case we’d forgotten the fairy-tale frenzy of it all. Elsewhere, similar riffs are all but non sequiturs, including the plot of Swan Lake, a snippet about notable ladies-in-waiting, a definition of a “Sloane Ranger” (an upper-class lady living in tony Chelsea), and a quick history of Kensington Palace.

With an insider view of the dance world, including ballet life and the staging of musicals, Allan does offer some fascinating asides. In this manner, her personal story drifts in and out and gives context to the fleeting moments she had with Diana. Allan changed jobs, had children, went on tour to Japan, got divorced. Although these memories are heartfelt, they’re disjointed in presentation.

Their classes, Allan confesses, often involved as much conversation as dancing. Clearly Diana loved to chat and had the ability to make people feel that they were among her most trusted confidants. But did she solicit or accept advice? Even if she did, most interlocutors likely didn’t feel empowered to offer any. They were there to listen (or, as it turns out, listen and transcribe). “She was a little worried about the attention she got as it seemed to bother Charles a bit,” Allan concedes, though that concern didn’t stop Diana from wondering “how lovely it would be to feel what it was like to do a performance.” This musing led her to ask Allan to organize a Covent Garden dancing debut at the high-profile Annual Friends Gala. Allan couldn’t resist: “I decided to see if I could make this dream of hers happen.”

A friend might have pointed out that surprising your insecure husband with an unprecedented royal performance would certainly make international news and would once again upstage him. They might have suggested it was not a wise move. All these years later, Allan describes that evening at Covent Garden as something of a coup, because Diana performed so well. Allan does not grant that she might have enabled a willful, naive impulse by the princess that she should have discouraged instead.

Throughout the book, Allan refers to her student’s difficulties with body image and eating disorders. The two discussed both in regard to other dancers, and one day Diana finally confessed, “I suffer from bulimia.” Her transformation from a healthy-looking young woman to a rail-thin fashion plate was always an excuse for media innuendo. Allan certainly knew about the rumours and was staring at Diana’s body regularly as it melted away. She wonders if she “should have been more forceful when suspecting there might be a problem,” but she ultimately lets herself off the hook. Perhaps proximity to stardust is not something anyone wants to jeopardize by telling their famous friend what they don’t want to hear.

Lots of unhappiness and many tears accompanied the lessons, and Allan describes the requisite breakdown moment shortly before Diana’s divorce, though she’s somewhat reticent to do so in full. Diana was unhinged after the Palace phoned Allan to say, “The Princess may want to stop her dance classes and do something else.” If gaslighting was part of the Firm’s plan to discredit her and move her off stage, it was certainly working, given Diana’s volatile emotional state. And here is where all those “extraordinary” qualities feel the most like PR concoctions. Diana obviously needed help and wasn’t getting it. She acted not like an extraordinary person but rather like an average one — unprepared for the exceptional circumstances that had swallowed her, with the entire world relishing her indecorous flailing.

Like many others no longer useful to the rich and powerful, Allan did the dutiful thing and receded into the background after the lessons ceased. While she may have felt rejected or forgotten by Diana, her consolation prize was the material for an effusive moneymaker about their ephemeral friendship.

Kelvin Browne wishes Savannah weren’t in the United States — so that he could visit again.