Is there such a thing as a truly national newspaper anymore? This question haunted me as I read A Nation’s Paper, an entertaining and informative essay collection about the Globe and Mail, one of North America’s most influential news organizations, and the seminal role it has played in the events that have shaped Canada.

In the United States, where I was the most senior news editor at the New York Times, the answer to that question would surely be no. News consumption south of the border is as polarized and balkanized as the politics. Times readers are concentrated in the progressive, highly educated, affluent urban areas of the country. Think of it as the national newspaper of Blue America, the part of the country that voted for Kamala Harris. For news consumers in Red America, those who get their news from Fox and conservative podcasters, the Times is viewed as a left-wing rag, publishing what Donald Trump calls “fake news.”

It isn’t only politics that divides newspaper readership in the U.S. It’s also technology, particularly social media platforms, where more than half of Americans get their news. YouTube, Facebook, and the like have shattered the old news media hierarchy and created a different landscape entirely, where everyone can design their own aggregated diet of stories that conform to their existing interests and politics. The lightning speed of the digital revolution has both democratized journalism and fragmented it. Many Americans feel they are drowning in news, and not all of it is produced by professionals.

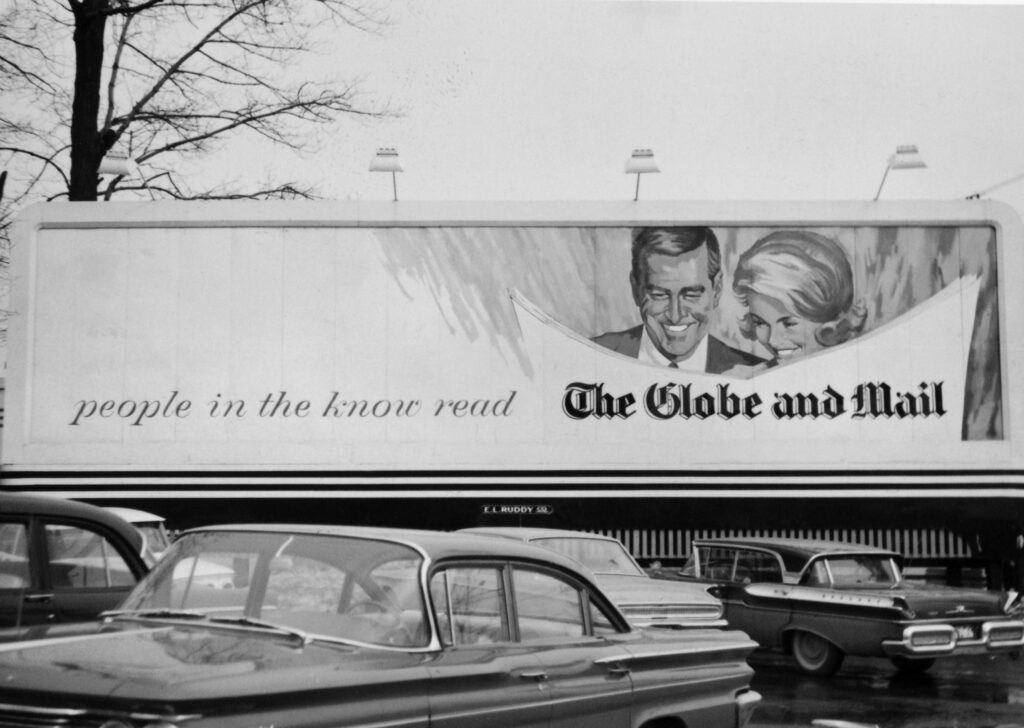

A billboard from 1962, the year the Globe launched its stand-alone Report on Business section.

Arthur Austerberry; E. L. Ruddy Company Limited; City of Toronto Archives

Canada’s experience has been slightly different. The Globe and Mail is still widely read and respected, both in print and online. Reduced distribution and the internet have cut into the physical paper’s readership, though it retains a national sensibility. In the U.S., the few other papers that once saw themselves as national publications, like the Washington Post and the Los Angeles Times, have managed to stay alive only because they have been bought in recent years by billionaires like Jeff Bezos and Patrick Soon-Shiong. The Globe has been in the hands of the wealthy Thomson family for much longer.

Reading this illuminating history of the Globe and Mail was, for me, a tonic. A Nation’s Paper covers the full 180-year life of the organization, from the original Globe’s founding by George Brown to its merger with the Mail and Empire in 1936 and on to the present. This is a vivid story of a bygone era, when a single publication with a large and broad readership could still serve a crucial role in uniting vastly different parts of a huge and important country. Having a true national newspaper may be one of the reasons that Canada — not immune to polarization, of course — has so far avoided the rancid divisions that have overtaken American politics.

As general editor of the Globe History Project, the writer at large John Ibbitson has gathered thirty essays by dozens of Globe alumni, who chronicle in fascinating detail the key events in Canada’s history where the paper played an important role, either in a pressing political issue, like Quebec independence, or in the nation’s cultural life. There are gripping pieces about the mistreatment of children in residential schools and about the growing influence of women, both in the country and inside the newspaper. The collection is not strictly a history of the Globe, in other words. Almost all the essays manage to shed light on the intimate and sometimes prickly relationship between nation and paper.

For an outsider coming to this anthology, the most captivating essay is the first one, penned by Ibbitson himself, about the Globe’s founder, George Brown, and the instrumental role he played in both Canadian journalism and politics. Brown was only twenty-four when he left Scotland for Toronto in 1843, a time when everything in Canada was, as Ibbitson aptly describes it, “newborn.” The place Brown encountered was a vast, scattered group of lands, each with its own distinct culture. The battle to unify Canada and create a real country gave him the biggest challenge but also the biggest achievement of his life.

The dramatic battle over Confederation pitted Brown and the Reform Party he built against John A. Macdonald, leader of the Conservatives. Their enmity was so great that the two men couldn’t stand to be alone in the same room. In their early political fights, Macdonald often had the upper hand. In the pages of the Globe, Brown strongly argued that “the people of Canada must be nationalized.” Eventually, after years of fighting, Macdonald came to agree, and the sworn enemies became allies in the creation of a united country. The chapter also includes a charming portrait of Brown’s wife, Anne Nelson, who helped mellow him and, as the historian Frank Underhill once wrote, may have been “the real father of Confederation.”

Brown was a journalist involved in politics who saw no conflict in using the Globe as a bullhorn for his political dream. Papers aligned with political parties were also common in the U.S. in the 1800s, but the standards of editorial independence today would make it impossible for a newspaper publisher to simultaneously hold or even seek office. When the former New York mayor Michael Bloomberg ran for president in 2020, for example, Bloomberg News kept a guarded distance from his campaign. Similarly, it would have been unimaginable if Chrystia Freeland, whom I knew as a reporter when she and I both worked in Washington, had continued to cover politics after she was elected to Parliament in 2015.

The book is brutally honest about the Globe’s past insensitivity toward immigrants from Asia and eastern Europe, and it rightly calls the residential school system “a national disgrace.” It is also forthright about the lack of women in top editorial positions — a failing I recognize from having risen through the ranks of the New York Times, moving from reporter to become the first and so far only woman to lead its newsroom.

The Globe’s editors realized early on that what were originally called “the women’s pages” made money, but those pages became a ghetto for the paper’s female journalists. A Nation’s Paper includes colourful portraits of pioneers like the star sportswriter Christie Blatchford, for a time one of the few women covering professional teams. She did so with a “tough and witty exterior,” but she left for the rival Toronto Star in 1977, because being one of only a handful of women at the Globe was, as she later wrote, “isolating and unnerving.” Blatchford’s comments rang true to me, especially considering the early days of my career, when I covered politics alongside a virtually all-male press, in their uniform of blue blazers and khakis. Back then, I was rarely invited to join “the boys on the bus” for drinks and campaign gossip. Later, when I became an editor, I was still often the only woman with a speaking part at most conferences and meetings — because organizers usually felt they needed to have at least one of us present.

There has often been a significant pay gap between male and female journalists, a shortcoming the Globe belatedly tackled with some success in the early 1990s. More recently, it looked outward at the rest of Canada with its investigative Power Gap series, which examined inequities between men and women in fields like law, medicine, and academia. While the recently retired columnist Elizabeth Renzetti describes gender equality at the Globe as improved, she ends her chapter by noting that women may now be at the table where the top editors make the most important decisions about news coverage, but “the best seats, at the head of the table, still remain out of reach.” (That’s not the case across town at the Star.)

Unsurprisingly, one perennial topic that has consumed editors at the Globe is Quebec’s relationship to the rest of Canada. At its founding, the paper was “hostile toward French Canada’s cultural and religious protectionism.” More than a century later, in 1980, its editorial board urged readers to vote no in the first sovereignty referendum. Its news pages were more sensitive to Quebec’s “peculiar interests,” which is perhaps no surprise. (At the Wall Street Journal, where I worked for a decade, it was not unusual to find its conservative opinion pages offering different takes on national issues than the news pages.) On the difficult Quebec question, Konrad Yakabuski concludes, “Whenever possible, The Globe has advocated for the accommodation of Quebec’s differences within the federation. It has not always been easy to square this circle in Charter-era Canada.”

A Nation’s Paper is well-stocked with delicious anecdotes, especially the chapter devoted to its sports coverage. There, tucked in the middle of Cathal Kelly’s review of what in olden times was called the “toy department,” is a lovely kernel of broader truth, an assessment of the surpassing value of quality writing: “This is what happens when you work with people whose journalism really matters. It gives you a freeing sense of perspective. Important human stories that just happened to involve sports would also be told.”

This book doesn’t only look backwards. It also tackles serious contemporary topics, like the difficulty of keeping enough reporters on staff to cover Canada and the world at a time when revenues are shrinking. One of the most painful decisions the Globe has made in recent years was to close almost all of its international bureaus, which it began opening only in the 1950s. The timing of these cuts — just as Canada’s international role was growing — was terrible. Again, this move resonated with me. While I was at the Times, budgetary pressures forced me to make certain trade‑offs in coverage, but I was lucky to work for a publisher who was fiercely protective of our international reporters and bureaus. Today the Times is, in a certain sense, a global newspaper if not a national one, with some 11 million paying subscribers and bureaus from Europe to Australia.

Running a paper — however global, national, or local — carries with it great moral, financial, and cultural responsibilities. Those involve both joy and, at times, terror. During my career, I had to deal with all kinds of emergencies, including reporters being kidnapped, a topic that thankfully doesn’t come up in these essays, though it certainly has affected journalists from other Canadian outlets. Ultimately, A Nation’s Paper shows how the Globe and Canadians have grown up, almost in lockstep, helping to build a strong and fascinating country together.

Jill Abramson served as executive editor of the New York Times from 2011 to 2014.