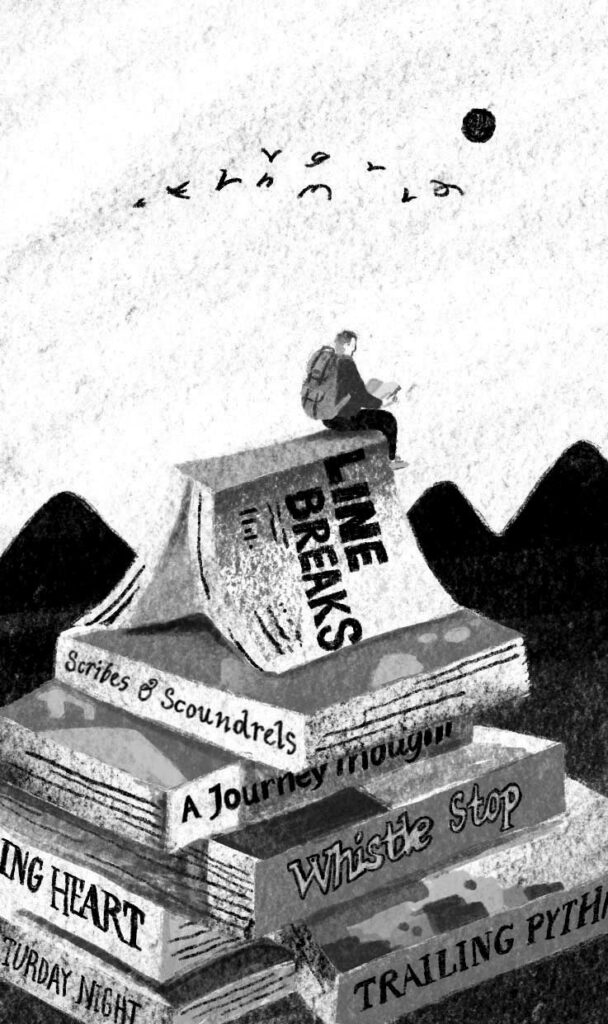

In Line Breaks, George Galt reflects on the past. He acknowledges that “lives are accidental in more ways than many of us are ready to admit” and perceives the course of his own life as “a series of accidental transits.” Now in his mid-seventies, Galt avows that he was not “an ambitious life planner” or “a lifelong journalist” and refuses to inflate the years he laboured as a writer and editor into a career. I admire Galt’s candour. After perusing his appealing narrative, readers are likely to feel a similar appreciation.

In reviewing his writing life, Galt considers his origins. He was born in Winnipeg in 1948 to parents who were devout Christian Scientists. When he was an infant, the family moved to Montreal, and he spent his first ten years in the Town of Mount Royal, where he attended public school. His mother was a homemaker, and his father was employed by Sun Life. Thomas Galt was president from 1972 to 1978; he and his wife relocated with the firm to Toronto in 1978. Thomas traced his ancestral roots to the Scottish novelist John Galt, who established the city of Guelph, Ontario, and worked in Canada for two years. Back in Britain, John Galt was incapable of managing his personal finances and was interned in debtors’ prison for four months. This tale, entrenched as family lore, helps explain Thomas Galt’s practicality and prudence.

Surveying a personal history of letters.

Nicole Iu

George Galt found the “cerebral religion” of Christian Science difficult to explain or love. From a young age, he was “a reluctant and doubting adherent,” which led to “one of the roughest” points of friction with his father. Their discord deepened when Galt was transferred to Selwyn House, a private boys’ school, where beatings were frequent.

For high school, Galt attended Bishop’s College School, an Anglican boarding school for boys in the Eastern Townships. He depicts its insular scholastic environment, which had served Quebec’s elite anglophone community since its founding in 1836. In this militaristic and regimented atmosphere, thrashings continued. Galt was among the lucky ones to escape sexual predation by the pedophile priest Harry Forster.

After Bishop’s, and once again living at home, Galt was given no choice by his “autocratic” father but to enrol at McGill University. He was so unhappy — one lecturer “nearly ruined” his love of literature — that he dropped out after one semester. At the time he was “an angry young man” who sought independence. After two years as a bank teller, he returned to learning, this time at Sir George Williams University (now part of Concordia), where he studied French, as well as Québécois literature with the separatist Léandre Bergeron.

Never an ardent student, Galt completed his undergraduate degree but decided to depart from “Montreal’s political hothouse.” In 1970, with Quebec nationalism taking hold, he felt conspicuous as the English-speaking “enemy”— though his affinity for the city endures to this day. He also had literary aspirations and meant to try his hand at writing a novel. His father was “suspicious” of that goal, which gave Galt an added push to leave.

Soon serendipitous encounters and events guided Galt’s otherwise “inchoate” path. He spent his first cash-strapped summer away from Montreal in Saint-Pierre, where he met the journalist Larry Zolf, who was staying on the Atlantic island to learn French. Fay, the Zolfs’ babysitter, became Galt’s first wife. During their marriage, they lived in Toronto, London, Ottawa, and later Prince Edward County, Ontario, in a stone house on Hay Bay. Their union was characterized by a series of unsatisfying jobs (including Galt’s brief stint at the Heritage Canada Foundation) and financial strain, as well as extended stays in Greece, Peru, and Bolivia. A serious car accident in Ottawa in 1976 left Galt with three broken ribs, an injured leg, and chronic headaches. During his prolonged recovery, he began psychoanalysis, which he credits with having saved his life.

The year 1982 saw the birth of Galt’s daughter, Vanessa, as well as the publication of his first book. Trailing Pythagoras, based on the author’s Greek travels, was reissued in 1988 as A Journey through the Aegean Islands. But Galt concedes that he was an inattentive husband and parent, and in 1987, just as he “was pushing forty,” he and Fay separated. That same year, he released a second travel account, Whistle Stop, a record of his four-month train journey across Canada from Sydney, Nova Scotia, to Prince Rupert, British Columbia.

The need for a steady income drives this reminiscence as much as it drove Galt’s every day. Once he became a father, he settled in Toronto and abandoned “the dream of becoming a full-time writer of books.” As a freelance journalist, he wrote feature articles and profiles for Saturday Night. Then Bob Fulford, the editor from 1968 to 1987, invited him to join the magazine’s staff. Galt happily accepted the offer, which came with a regular weekly salary of $700. Fulford, who died in October 2024, left his mark. Galt recalls the man’s “extraordinary memory,” informed opinions, and colourful conversation, as well as his “large ego needs.” Galt remained at the magazine under John Fraser, who was the editor from 1987 to 1994. Fraser was energetic, quick, and ambitious. That he was also “open to experimentation” was a boon to Galt.

Assignments brought him into contact with prominent writers and cultural and political figures. Galt’s depictions of the diarist Charles Ritchie and the actor Peter Ustinov, like those of Margaret Atwood and Pierre Trudeau, display novelistic skill. However, it’s Al Purdy who reigns as the commanding “literary father figure” in Galt’s life. He met the poet in 1978, when he was in need of an entrancing mentor. They bonded over books and booze and went on to form a “long and sometimes intense relationship.”

Galt, who grew strategically attuned to Toronto’s “cultural pecking order,” was instrumental in reviving the English-language centre of PEN Canada and in establishing the Woodcock Fund of the Writers’ Trust of Canada. He stepped down as chair of the trust’s board of directors in 1998, one year after the publication of Scribes & Scoundrels, his long-delayed novel. Galt regards his subsequent years studying and teaching history at the University of Toronto as relatively “quiet” and so ends his chronicle in 1999 — though his preface reveals that he and his wife now live near Vanessa on the West Coast, where he founded the small literary publisher Stonehewer Books in 2022.

As this polished memoir shows, Galt’s life of “accident” has been anything but subdued, and he is the writer he always envisaged.

Ruth Panofsky teaches English literature at Toronto Metropolitan University. She recently received the Royal Society of Canada’s Lorne Pierce Medal.