Book banning, a pernicious form of censorship, is as old as the book itself. Ancient Romans banned those that contained political criticism or discussed topics deemed immoral, though given the facts of ancient androgyny, pederasty, and bestiality, it seems puzzlingly hard to draw a clear line between moral and immoral. Ironically, Romans of social standing had private libraries, many of which were destroyed by the Goths. Centuries later, the Catholic Church instituted its bans of 1599, a few decades before the first book was suppressed in the future United States (Thomas Morton’s New English Canaan, which was critical of Puritan customs and powers) and almost 300 years before Canada’s state-sponsored censorship regime began under the Customs Act of 1867.

In many respects, as Ira Wells shows in On Book Banning, things are even worse today. “Where book banning once largely involved the legal and disciplinary apparatus of the state, the new censorship consensus works through both state actors and a constellation of special interest groups operating inside and outside of institutions,” he writes. “Their target is libraries: public libraries, in which all taxpayers have a stake, and especially school libraries, which can be uniquely vulnerable due to chronic funding shortages and lack of full-time librarians able to cultivate their collections over time.”

Libraries prove to be ripe targets, especially because they are “one of the last public institutions committed to intellectual freedom.” But apparently the only freedom that matters to censors and banners is their own. Would‑be saviours, false prophets, crackpots, and perverse politicians are modern-day incarnations of those who for centuries burned with ardour to save others from the sins and crimes they most feared themselves. In schools, universities, town halls, senates, and parliaments, the walls resound with Orwellian doublespeak. The censorious proselytizers may not yet have produced an official Index librorum prohibitorum, but they certainly have assorted criteria for weeding and banning titles, chiefly if not fully based on their religious, political, and social biases.

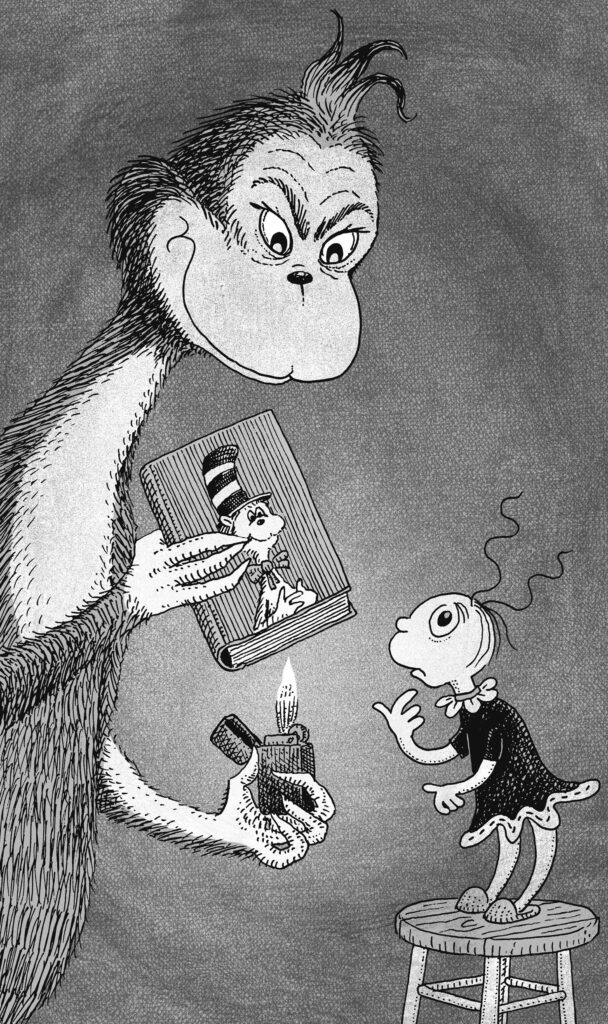

His sophistication was two sizes too small.

Tom Chitty

Often the expurgators demonstrate a shocking inability to read at any level beyond the literal. Infected by literary and moral blindness, they soldier on — seemingly immune to mockery of their absurd platitudes. Their first marks are books for early readers and what is broadly termed young adult literature. They seem to echo Donald Trump, that self-styled expert on gender. Boys should be boys, and girls should be girls: never queer. Therefore anything that smacks of “a trans boy” (When Aidan Became a Brother) or two male penguins raising a chick together (And Tango Makes Three) is heresy to these latter-day puritans. I don’t take Oscar Wilde as gospel, but he was epigrammatically shrewd, as in this declaration from The Picture of Dorian Gray: “There is no such thing as a moral or an immoral book. Books are well written, or badly written. That is all.” Such clarity is totally absent from the sensibilities of book banners and of many chief executives of arts granting bodies, for whom aesthetic quality is the least important.

“When some cultural critics fret about the ‘ever-more-appalling’ YA books, they aren’t trying to protect African-American teens forced to walk through metal detectors on their way into school. Or Mexican-American teens enduring the culturally schizophrenic life of being American citizens and the children of illegal immigrants. Or Native American teens growing up on Third World reservations. Or poor white kids trying to survive the meth-hazed trailer parks. They aren’t trying to protect the poor from poverty. Or victims from rapists,” the Spokane novelist and filmmaker Sherman Alexie wrote in the Wall Street Journal more than ten years ago. “No, they are simply trying to protect their privileged notions of what literature is and should be. They are trying to protect privileged children.” Censorious North Americans detest hearing such hard truths, because they simply confirm that banning a book does not automatically lead to preventing any of the sins or crimes referenced in its pages. Indeed, money and religion often misspeak in the name of freedom.

With this slim volume, Wells lays out cogent arguments against culture warriors who continue to warp our children’s relationship to literature. His subtitle sets the focus: How the New Censorship Consensus Trivializes Art and Undermines Democracy. I don’t personally believe that much-touted democracy has ever truly existed in the United States, which, after all, was given its economic strength, constitution, and “moral” path by slave owners. And I see no evidence of true democracy under Trump and his MAGA disciples, who contaminate the body politic with monstrous ignorance, paranoia, and fascism masquerading as Christian righteousness. But I willingly subscribe to Wells’s multi-pronged discourse, which identifies paradoxes of censorship. First, “book banners assign extraordinary power to books at a time when, by objective measures, books and literature seem to matter less and less.” Second, “in an era where book banning feels less feasible than ever, more and more people are attempting it, which forces us to think again about their goals.” Besides, bowdlerizers on both the right and the left “ignore the cyclical nature of censorship, presuming that the new censorship apparatus won’t eventually come for them.”

Wells recalls his own experience in the spring of 2022, when the principal at his children’s elementary school recruited a group of parents for a “library audit.” Beneath an objection to Eurocentric, male, heteronormative “old books,” Wells detected a dangerous, fast-spreading dogma that insulates itself against intellectual challenges. His children’s school provided an “equity toolkit” with which to conduct a severe audit of the library, but the very term “equity” is questionable for being “an umbrella term for anti-racism, anti-oppression, gender inclusivity, and Indigenous advocacy” that was already “at the heart” of its work. What would “the equity perspective” have to say about Charlotte’s Web, Where the Wild Things Are, or Bridge to Terabithia?

A literature professor at the University of Toronto, Wells persuasively explains how book banning reduces and devalues art and how it constitutes an attack on intellectual autonomy and on “your right to determine the future of your own mind.” I concur, especially given the influence of literalist readers (many of them, alas, certified teachers) who show no understanding of literary textures or sophisticated forms and for whom books are reduced to simple moral lessons or messages. Such “readers” would be better served by telegrams than by books.

Arguably, the epicentre of contemporary book banning is Florida, where one high school teacher, Vicki Baggett (unburdened by literary expertise), has challenged more than a hundred titles. Apart from her, there is a plague of Bible-thumpers eager to denounce whatever they deem flat-out abominations, though conveniently forgetting that the Bible itself (especially the Old Testament) is rife with allusions to abominations. Wells states that by the end of 2023, more than 1,600 books, including the Merriam-Webster’s dictionary (with descriptions of sexual acts that might constitute pornography under Florida law) and works by Anne Frank, Toni Morrison, Cormac McCarthy, Stephen King, Jonathan Franzen, and Margaret Atwood, as well as Guinness World Records and Ripley’s Believe It or Not!, had been targeted in and around Pensacola. To compound the insanity, the state’s Republican governor, Ron DeSantis, signed legislation “to preserve the rights of parents to make decisions about what materials their children are exposed to in school,” suggesting, in effect, that kids might be exposed to degeneracy unless Mom and Dad were given the right to approve what was being taught. (Isn’t that akin to giving parents the right to approve scientific experiments in fields totally beyond their expertise?) No amount of “vaguely Orwellian language” could disguise the fact that pornography was DeSantis’s central concern, along with anything smacking of “obscenity,” “indecency,” or “scurrilousness.” Of course, those are impressive words that no law has successfully defined in unimpeachably objective terms — but that’s no problem for alarmists, whether in Florida or in Ontario’s Peel Region, where a “book weeding” directive applied to nearly 260 schools. “Some of them threw out thousands of books,” Wells writes. “The total number is unknowable.”

Wells summarizes 2,000 years of censorship in the West, surveys the philosophic and legal foundations of expressive freedom, and describes various intellectual challenges to that freedom. In his final chapter, he considers how we might “futureproof” our freedom to read against an onslaught of misinformed adjudicators. To do so, we must acknowledge that even well-intentioned “foundational thinkers of expressive freedom” have mucked up the issue, including John Stuart Mill and John Milton, whose Areopagitica is especially influential: “Milton was prejudiced against Catholics; J. S. Mill supported and worked on behalf of English colonialism in India.” However, “these failings no more invalidate the ideal of expressive freedom than Albert Einstein’s cruelty toward his wife invalidates the theory of relativity.”

Wells sounds a soft note of regret as he concludes with a proposal to renegotiate “the norms around public and private spheres,” while also appealing for careful thought “about the scope of education within highly diverse, pluralistic democracies.” When parents and politicians accuse educators of “indoctrination,” they must be challenged by a clearly articulated line of division between educated critical thinking and blind submission to fatuous doctrine. Unlike censorship, literature must not be reduced to “a shrunken, misshapen parody of itself.”

Keith Garebian has published thirty books and five chapbooks, including the poetry collections Three-Way Renegade and, most recently, Stay.

Related Letters and Responses

@yvetteleclair via Instagram