Margaret Atwood resisted autobiographical writing for years. “That would be tedious,” she says at the beginning of Book of Lives. “You’ve heard the bad joke about the old East Coast fisherman counting fish? ‘One fish, two fish, another fish, another fish, another fish . . .’ So, my ‘literary memoir’ would go, ‘I wrote a book, I wrote a second book, I wrote another book, I wrote another book . . .’ Dead boring.”

What changed her mind?

Well, time passed, for a start. And her “sinister alter ego whispered” in her ear: “I could thank my benefactors, reward my friends, trash my enemies, and pay off scores long forgotten by everyone but me. I could spill some beans, I could dish some tea.”

Atwood does all of the above in Book of Lives, some of it repeatedly.

She also changed her mind because “people die, and after they do, things may be said about them that might have been held back before.”

Before her introduction, Atwood quotes a few voices from her past and present, beginning with this exchange:

You were such a sensitive child! — MY MOTHER

But I’m quite flinty now. — ME

Yes. You are. — MY DAUGHTER

Then in her introduction, which is prefaced with an allusion to doppelgängers, she tells a fun story about the television personality Rick Mercer persuading her to make a stunt appearance on his show as a hockey goalie: “So I was a goalie, in a full set of pads, with gloves and a stick. There I am on YouTube, still goalie-ing it up; and yes, it is kind of funny.”

A body double did the actual skating. “It’s the job of the body double to take the risks you yourself are too sedate or chicken or unaccomplished to take,” she explains. “I wish I could have a body double in my real life, I thought. It would come in so handy.”

And here comes the Atwood twist:

Of course, I do have one. Every writer does. The body double appears as soon as you start writing. How can it be otherwise? There’s the daily you, and then there’s the other person who does the actual writing. They aren’t the same.

Sensitive and flinty, Atwood and her body double. Body doubles, in fact: “In my case, there are more than two. There are lots.”

You know that one about the legendary author counting her books?

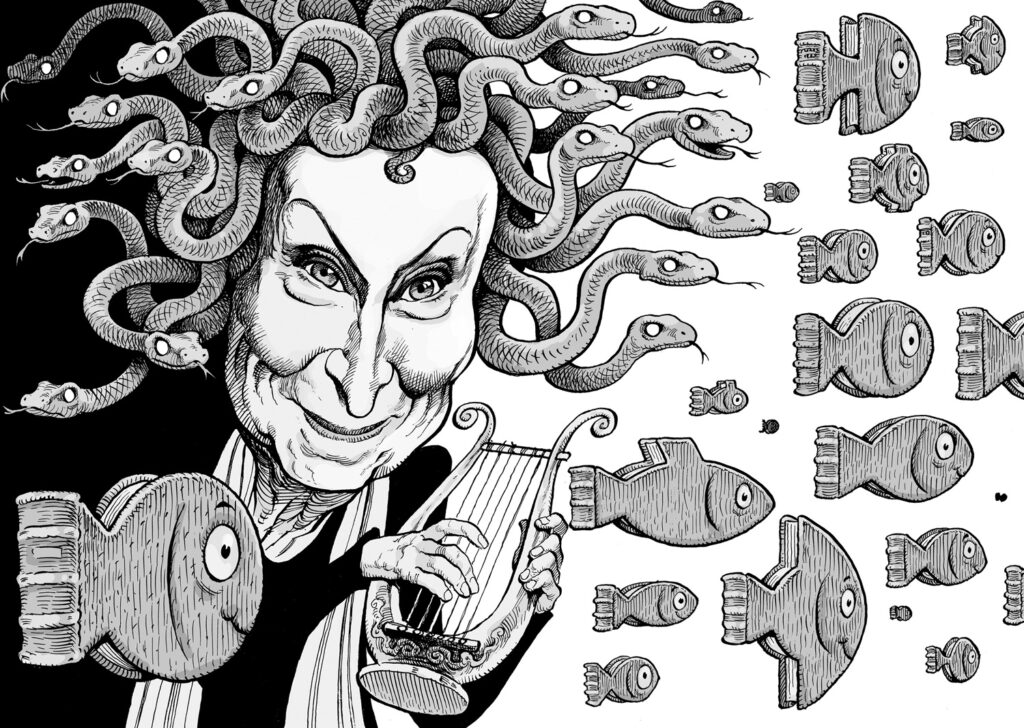

David Parkins

Medusa being one alter ego, Atwood compares both her hair (“curly and/or frizzy and/or Pre-Raphaelite”) and her eyes to those of the mortal Gorgon: “One glance from my baleful eyes and strong men weep, clutching their groins, lest I freeze their gonads to stone with my Medusa eyes.”

Unlike Medusa, however, Atwood is droll. Also quick, intelligent, smart, shrewd, varied, multi-faceted, playful, unpredictable, cunning, and mercurial.

If it’s not enough to view her as Medusa, it’s at least as difficult to see her as a sunny, lyre-strumming Apollo busying herself with structure and harmony. As she’s casting about for a doppelgänger, she mentions another son of Zeus, Hermes, “god of tricks and jokes and messages, concealer and revealer of secrets, patron of travellers and thieves, conductor of souls to the Underworld.”

Is she, then, a frizzy-haired Hermes figure with baleful eyes, strumming a lyre? Not quite.

Atwood is a storyteller, most of all, and her Book of Lives is full of memorable stories, some of which are funny and some of which are not funny at all. Atwood can be toxic, too, the way mercury is toxic, and many of her stories are enlivened by her wicked delight in trashing people who did her wrong.

Here’s another example from the telling epigraph page:

Don’t piss her off, or you will live forever. — JULIAN PORTER, MY FRIEND

Dorothy Livesay will live forever. Middle-aged and hostile when Atwood was teaching in Vancouver in the mid-1960s, Livesay “continued to jealously dislike me and undercut me as much as she could, a program she continued all her life.” You’ll have to read the book to discover how Atwood gets her own back on Livesay.

When The Edible Woman was published in 1969, Atwood got a reputation for eviscerating anxious, jealous, and condescending journalists. This is “only partly deserved,” she protests. “I never eviscerate interviewers unless they attempt to eviscerate me first.”

And if you still don’t believe her friend Julian Porter, you might like to check out Atwood’s vitriolic account of Shirley Gibson, who was Graeme Gibson’s estranged wife, mother of their two sons, and the president of the House of Anansi Press when Atwood was sitting on the board of directors in 1972. If anyone will live forever, Shirley Gibson will.

A few of Atwood’s targets escape unnamed, if not unscathed:

“She writes like a man,” a fellow poet said of me in the early 1970s, intending a compliment.

“You forgot the punctuation,” I told him. “What you meant was, ‘She writes. Like a man.’ ” Ripostes of this kind came in handy at the time.

Atwood’s mother and father were married in rural Nova Scotia, but they moved into the northern Quebec bush after he was hired by the federal Department of Agriculture as an entomological field researcher. Margaret and her older brother, Harold, spent most of their childhood in the wilds.

Young Atwood was a timid outsider with a funny accent and weird hair when she went to school in Toronto; when she was nine years old, three of her classmates decided they needed to “improve” her. They were cruel, and she was traumatized. And here, as happens elsewhere in her book, Atwood interrupts her mostly chronological account to move decades into the future to tell us how she recreated an experience in her writing. The childhood abuse she suffered in grade 4 reappears in her novel Cat’s Eye, from 1988, where she calls the ringleader Cordelia.

On a happier note, she adds that Cat’s Eye was nominated for the Booker Prize, and that the students at Victoria College, her alma mater, chose to name their campus pub the Cat’s Eye. “Now that,” she writes, “is an achievement.”

She was sixteen when she wrote her first poem, walking home from school:

I hadn’t been a poet when I got up that morning, but by the time I reached the end of the football field I was one. A bad one, true, and the poem I’d composed in my head had only four lines, but I was so intoxicated by it that I stepped off the path I was on — by that time it was leading in the direction of biology — and took another, the one that eventually wound its way, via many twists and turns and detours, to the book you are now reading.

Why poetry? Where did that come from?

After a brief attempt to address that question —“There is no reliable why, as far as I can tell”— Atwood veers off into some of the reasons one might not want to be a poet. But she also tells us about Miss Bessie Billings, the inspiring grade 12 English teacher who was “probably the first person to encourage me as a writer.” (Billings also appears in the story “My Last Duchess.”)

Atwood’s evidently accomplished essay on mushroom hunting led Miss Billings to praise her in extravagant terms to another teacher:

Truly, a remarkable piece of work! What a feeling for words and what an observant eye. Also she must surely write for the love of writing. We should give her every encouragement — tell her now that a scholarship and great satisfaction — both are within reach.

At the end of several chapters about her childhood, Atwood’s story moves into a higher gear in 1957, when she enrolled at the University of Toronto. There she met Dennis Lee, a fellow student at Victoria College who was “obviously brilliant, having won the Prince of Wales scholarship for top marks in the province.”

“Keep your eye on Dennis,” she commands (she can be bossy). “He has a major role to play. Robertson Davies, in his outstanding novel Fifth Business, defines a fifth business as a character who is neither the hero nor the heroine, nor is he the antagonist. Instead, he’s the one who sets things in motion, often unwittingly.” The future author of Alligator Pie was to become “the fifth business of a major part of my life.”

During her undergraduate years, she spent summers at Camp White Pine, in Haliburton, Ontario, where other pieces of her life started falling into place. She met Charlie Pachter, who later became an artist and a lifelong friend. Known at camp as Peggy Nature — which remains “one of my disguises”— Atwood was working out of her nature hut, while Pachter was a “bratty fifteen-year-old” working as the camp’s assistant arts and crafts teacher.

Rick Salutin — now a playwright, journalist, memoirist, and another good friend — turned up next, on a visit to see Pachter.

Rick was a pious, obnoxious, sanctimonious twerp in those days, as he himself now freely admits. He said later that he did all that praying to annoy his father, who was very secular, a compulsive gambler, and an actively unpleasant dad. Once Rick had got over his praying and had ventured out onto the sea of letters, he sought me out for my vast experience — at age twenty-seven — and we became close friends. When I wanted someone to go to the Barbie movie with me recently, whom did I choose but Rick? (He liked it.)

This is one of my favourite character sketches in Book of Lives. And on a personal note, I’ll add that one of the very few times I have met Atwood — with Graeme Gibson — was in 2012, at the Massey College launch of an essay by Rick Salutin that happened to be the first book published by Linda Leith Publishing.

The dynamic cultural scene that was emerging in the Toronto of the ’60s and ’70s is another character in Book of Lives, sketched here somewhat differently than in Atwood’s friend Susan Swan’s recent memoir, Big Girls Don’t Cry. This was the city in which Dennis Lee took his place across the table — often in the Red Lion pub on Jarvis Street — at meetings of the board of directors of the House of Anansi Press.

Around that table in 1972 were Graeme and Shirley Gibson, along with Atwood (then married to Jim Polk, whom she had met at Harvard) and an accountant, because Anansi was in serious financial trouble. Its very survival, in fact, depended on an idea that Atwood proposed for a book to be called, appropriately, Survival: A Thematic Guide to Canadian Literature.

Lee liked the idea, the others agreed, and Atwood embarked on the creation of that landmark essay along with Lee and others. After four months of crazily intense collective work, Survival was launched later that year. When it became a national bestseller, it saved the day for Anansi. It also paved the way for a world in which all the Atwoods and all their many associates could thrive.

Those of us who have followed Atwood’s career will know much of her story long before we crack open a copy of Book of Lives: her outdoorsy childhood, her graduate studies in American literature at Harvard, her scholarly interest in Puritan New England, her first poetry collections, her surprise Governor General’s Award for The Circle Game in 1967, and then the publication, in swift succession, of The Edible Woman, Surfacing, and Survival, not to mention innumerable other and more recent books, plus umpteen films, accolades, travels, and adventures.

The landscape she entered as an unknown changed radically in the 1960s, as “many of the Canadian publishing and writing institutions that we would later take for granted were formed.” If you were a Canadian who wanted to be a writer back then, you soon discovered that real writers came from somewhere else. You had to go to London, New York, or Paris to make a career, as Margaret Laurence, Mordecai Richler, and Mavis Gallant had done —“not that we knew who Mavis Gallant was yet.”

Atwood was working with many others who were reshaping the face of Canada. The rest of us, coming along in later decades, have learned from them — most especially from Margaret Atwood herself. We learned how to be writers, how to make literary careers as outsiders, and how we could be writers here in Canada. We learned how to create a framework for our own accomplishments and those of our companions — and not only in Toronto.

Those of us who are women learned how to be women writers. And — as Atwood and Graeme were soon a couple, and their daughter, Jess, was born in 1976 — some of us also learned how to be women writers with families. One or two of us might even have chosen companions with some resemblance to Graeme Gibson.

Atwood credits Gibson with creating the Writers’ Union of Canada and the Writers’ Trust, although, as she knows better than most, there were and are countless other literary figures and organizations that have played crucially significant roles in English, in French, and in other languages, right across the country. It cannot be denied, however, that Atwood herself was and is key to putting Canadian literary culture on the map both here and elsewhere.

Reading her, watching her, listening to her, and following her spectacular career, we have learned what to do and how to do it. We learn a great deal more of those skills — and much else besides — from Book of Lives.

However familiar we have long been with her public persona, we have known less about the private person who was abused in grade 4 and unsure of herself as a young woman. Even if we guessed the extent to which she was reading everything from psalms to palms, not to mention drawing, playing, exploring, and writing, we have been little acquainted with the loving daughter, sister, co-conspirator, partner, mom, and friend we get to know in these pages. By the time she is honouring the kindly Mrs. Sims, who was her compassionate boss at the market research company that figures in The Edible Woman, Atwood has revealed herself as anything but flinty.

We can’t help being aware of her as a public intellectual. We all know how famous she became, especially after the staggering success of her novel The Handmaid’s Tale, which won a Governor General’s Award for fiction in 1985, was shortlisted for the Booker, and then, decades later, became an international sensation as a result of the television series and the publication of a sequel, The Testaments, in 2019.

The closing sections of Book of Lives bring the vulnerable private person together with Atwood’s public persona. This is the moving story of Gibson’s dementia and his last days with her in London. Shortly after the launch of The Testaments, he suffered a massive cerebral hemorrhage; he was admitted to hospital for palliative care and died a week later.

Some people were surprised that I continued with the book tour for The Testaments. But ask yourself, Dear Reader: The busy schedule or the empty chair? I chose the busy schedule. The empty chair would be there when I got home.

It was difficult, though:

I think I looked normal during the book events, whatever “normal” had come to be. Then, at night, I was alone in hotel rooms. I’d been alone in hotel rooms a lot and never minded it: I could always phone Graeme. But now I was really alone.

Depending on your age, your background, and your own story, you might — or you might not — realize how extraordinary it is that Margaret Atwood has become such an iconic literary figure. She had some very lucky breaks, certainly, and was especially fortunate in her family, her friends, and her education, and in being in the right place at the right time. But even her critics must agree that she has made her own luck, most of the time. She’s the one who writes these books, after all. And she’s the one who deals with the misogynists, who are still around, in case you hadn’t noticed. Being flinty can be a necessity rather than a choice.

She was also disadvantaged in some ways, and not only as an outsider and as a woman. At the outset, she was a Canadian keenly aware of Canada’s literary reputation, or lack thereof. Part of the secret of her success, surely, is that she has refused to let the disadvantages discourage her. She acknowledges the truth, that Canada was indeed a provincial backwater — and then she puts her formidably sharp mind to good use, pointing out that the movement of a wheel is fastest at the edges. The centre remains static.

And she doesn’t stop there.

Not satisfied with turning a disadvantage into a clear advantage, she then focuses on other writers — writers like herself, writers blessed with neither wealth nor social status. It was rarely the English upper classes who were writing the books, she reminds us. The most impressive writers were mostly hacks and impoverished women with “inky fingers.” Some of them were stuck in provincial backwaters immeasurably far from the glittering metropolis: “So, I was from a provincial backwater and I had inky fingers. Deal with it, I admonished myself.”

Did she ever deal with it.

Margaret Atwood was right about autobiographical writing. It does have something in common with the fisherman’s joke she told at the outset: one fish, two fish, another fish. Grade 3, grade 4, grade 5. One story, another, yet another. Book after book after book.

But that’s a feature, not a flaw. Book of Lives is a remarkable accomplishment. It is, and it had to be, a big book, for Atwood’s is a big life. Oceanic, in a word, and teeming with great fish.

Linda Leith founded the Blue Metropolis Montreal International Literary Festival in 1998 and Linda Leith Publishing in 2011.