Ties That Bind

Traditional bookbinding involves folding, sewing, and gluing pages together to make a codex—or book—as we know it. Today, the process is often a commercial one, as sheets soar through factory machines and come out properly collated on the other end. But there are still craftspeople who bind books by hand; a small number even call it a career. Don Taylor is one such professional.

As a teenager in Windsor, Ontario, Taylor first encountered the practice in a 1959 Daily Mail Boys Annual article, “Bind Your Magazines into a Book.” Fascinated, he and a friend began taking the four-hour train ride to Toronto in search of old works to deconstruct and reassemble. On one such excursion, Taylor found a bona fide bookbinding manual. The rest, according to him, is history.

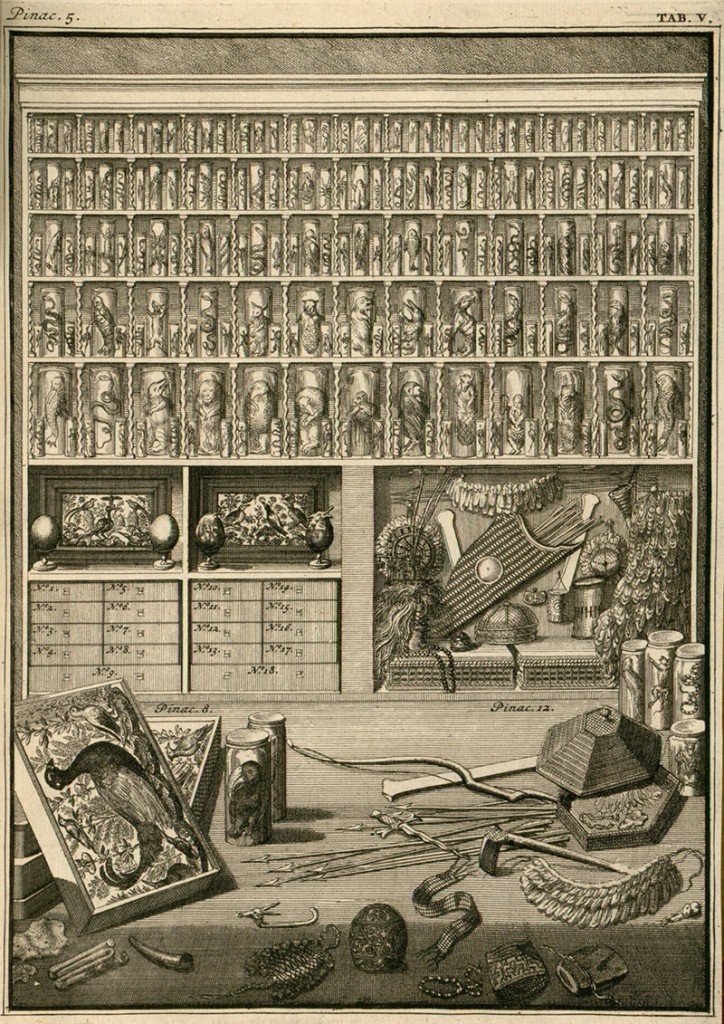

Projects of all shapes and sizes line Don Taylor’s studio walls.

In 1980, he set up shop in Toronto’s downtown core, sharing a building with artists, fashion designers, and other creatives. Four years ago, he was renovicted to make way for a bitcoin store. His operation moved to a repurposed warehouse in Etobicoke, about twelve kilometres west of downtown.

The imposing concrete structure contrasts Taylor’s small, delightfully chaotic space. (He admits to having trouble keeping things neat.) There are books in various stages of completion everywhere. Tools, such as awls and bone folders, litter the cramped workstations. Surrounded by the smell of old paper and the sounds of machines—like the guillotine that binders have been using for centuries—it’s easy to feel transported to a bygone era.

Mostly, Taylor does restorations, fixing books that have suffered the ravages of use and time. He also binds self-published titles, whose authors range from business tycoons to Holocaust survivors. While he produces fewer wedding albums than he did in the ’80s, his work hasn’t slowed down. Not even the trend toward digital publishing has made much of an impact. New clients consistently approach him with exciting projects: artists covering stones in case bindings, university administrators replacing ceremonial ledgers, producers requesting original props for films like Guillermo Del Toro’s Scary Stories to Tell in the Dark. Taylor tackles every venture with enthusiasm. “It’s very rare that we say we can’t do something,” he explains.

Somehow, he also finds time to share the tricks of the trade. He teaches at schools around the country, mentoring students through the Canadian Bookbinders and Book Artists Guild and at the University of Toronto. Thousands have passed through his courses, learning skills like hand-eye coordination and the ability to visualize in three dimensions, among others.

Ironically, the Daily Mail Boys Annual that inspired Taylor became a binding project in and of itself. Damaged in a flood, it now lives on one of the shelves lining his studio walls, among projects of all different shapes and sizes. Taylor has weathered many changes in the industry, and even a few recessions, but it seems that books aren’t going anywhere—and neither are the binders. As he says, “Forty years later and I’ve never been busier.”

Kirsten Brassard is a graduate of the University of Toronto’s book history and print culture program.

Originally published in the November 2, 2019, instalment of