Northrop Frye started teaching at Victoria College in September of 1939, just as Marshall McLuhan began his PhD in England. Frye had studied for the church and worked as a student minister. But he hated theology and could not talk with people, so he quit preaching for another pulpit, one from which he could invent his own theology and do more writing than talking. McLuhan loved talking but hated Winnipeg, and so, with the help of an American aunt and the Imperial Order Daughters of the Empire, he left Manitoba for Cambridge, first for a second undergraduate degree and then for a doctorate in medieval and early modern English literature. In the spring of 1946, he accepted an offer from St. Michael’s College, just south of Frye’s corner of the University of Toronto.

In the 1960s, Frye and McLuhan were the best-known Canadian intellectuals in the world. Even today, they remain the best-known humanities professors their university or their country has ever had. Frye’s Anatomy of Criticism, published by Princeton University Press in 1957, is the first and only book of literary criticism by a Canadian to become required reading for a generation of students and professors of English. By the mid 1970s, it was the most cited book in humanities scholarship by a 20th-century author, and Frye was the humanities’ eighth most cited scholar, behind Marx, Aristotle, Shakespeare, Lenin, Plato, Freud and Roland Barthes. McLuhan’s Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man made him required reading for anyone with intellectual pretensions, not just or even mostly English professors. It sold 100,000 copies in a pocketbook edition from Signet, on the cover of which the New York Herald Tribune declared McLuhan “the most important thinker since Newton, Darwin, Freud, Einstein and Pavlov.” A follow-up pocket anthology of McLuhan’s aphorisms published in the early spring of Canada’s centennial year sold a million copies worldwide.

Besides fame, they had much else in common—more than divided them, really, even if the differences are more important. For starters, they were both white men of the same age, place and time. They both grew up in small Canadian cities that were not Toronto, McLuhan in Winnipeg and Frye in Moncton. Both came from Methodist homes; Frye was ordained in Methodism’s gentler descendant, the United Church, and McLuhan converted to Catholicism. They both believed in God, whatever version. They both went to England to do doctorates in English literature, Frye to Oxford and McLuhan to Cambridge, although Frye never finished his and McLuhan turned his into something else. As teachers and critics, both mostly avoided evaluative or moral criticism in favour of close attention to style and structure, to how literature (or media, for McLuhan) works instead of what it says, how well it says it, or whether it is good for you or not.

Less commonly for their discipline and time, both chose to remain in Canada when they could have moved to American universities (partly because to keep them, the University of Toronto created an entirely new rank for Frye and gave McLuhan his own centre). Teaching was important to both, at a time when their profession was learning how to avoid it. They were both extremely ambitious, in a country generally uncomfortable with ambition. Both aspired to a theory of everything, a key to all that man had made or imagined. Both believed that criticism was literature’s equal, maybe its better.

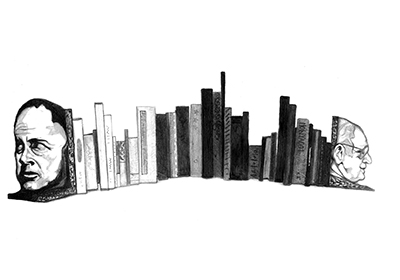

Gabriel Baribeau

According to B.W. Powe, McLuhan and Frye not only had more in common than we might think, but together they created a uniquely Canadian intellectual tradition. Until now, the small industries that are McLuhan and Frye scholarship had not produced a book on both, partly because fans of one are rarely fans of the other. Powe, a professor at York University who was a student of both in the late 1970s, says he was “never fully a McLuhanite or a Fryegian,” but from his book it is clear he is certainly a serious scholar and an ardent fan of both his teachers. In Marshall McLuhan and Northrop Frye: Apocalypse and Alchemy, he offers what he calls an appreciation and an extension of their thought. Along the way, he argues that the relationship between the two was a productive antagonism, a “coinciding of opposites,” that “initiated a -visionary-apocalyptic tradition in Canadian letters.”

McLuhan and Frye met for the first time at a faculty gathering at Victoria College in 1946, the year McLuhan was hired. In public, their relationship was polite, even friendly. Frye does not mention McLuhan in his main works, although he does in his notebooks, with remarks like “global village my ass” and “I never understood why that blithering nonsense ‘the medium is the message’ caught on so.” Still, he convinced a dubious selection committee to give a Governor General’s Award to McLuhan’s second book, The Gutenberg Galaxy: The Making of Typographic Man. He told a friend that he was “personally very fond” of McLuhan. “I don’t always agree with him, but he doesn’t always agree with himself.” After McLuhan’s death, he said he thought McLuhan had been praised for the wrong reasons during his vogue and ignored for the wrong reasons after it passed.

McLuhan wrote a favourable review of his senior colleague’s first book, an influential monograph on William Blake published in 1947. But he hated Anatomy of Criticism, and not just for its success. In a mercifully unpublished review, he called it “almost unreadable,” an odd criticism from a writer who deliberately confused his readers. By the time the Anatomy appeared, McLuhan was well on his way to working out one of his core ideas, the notion that the printing press had created a culture of specialists, a culture currently being “re-tribalized” by electronic media into a single, organic -consciousness: the global village. Frye’s systematic classification of literary species in the Anatomy—his attempt to make a specialized science of criticism—would have epitomized McLuhan’s sense that the end result of 500 years of print culture was professional myopia. Less understandably, McLuhan also seems to have believed that Frye was part of a clandestine Masonic chapter at the University of Toronto that was secretly opposed to him and his work. (Neither Frye’s nor McLuhan’s biographers have uncovered any evidence that Frye was a Mason, and opposition to McLuhan at the university was hardly secret.) Powe once heard McLuhan dismiss Frye’s thinking as “Protestant.” Frye taught us that although one poem can of course be better than another, literature itself never evolves or improves. All stories at all times by all peoples are parts and versions of a single story, the story about who we are, told in pieces, over and over. McLuhan taught us that no technology is neutral, that every tool changes not just our lives but our world. The typewriter, for instance, changed women’s fashion, and English prose style. The telephone created the call girl. In turn, we become the servants or “servomechanisms” of our technologies, in the way that “an Indian is the servomechanism of his canoe, the cowboy of his horse,” or you of your iPhone.

Those are Really Big Ideas, still. If we do not find them as compelling today as we did when they were new, that is because they are now the way we think. Gravity is no longer a terribly exciting argument, but that does not make it any less effective.

For those ideas alone—and as McLuhan said, if you don’t like those, I’ve got others—McLuhan and Frye may well be what Powe says, Canada’s “most necessary literary figures.” I might enjoy reading Margaret Atwood more, but novels are never necessary. As Frye showed, they have all been written before, and will be again. As McLuhan showed, no novel is more consequential than the technology that delivers it, no content more meaningful than its form.

But McLuhan and Frye both being important thinkers does not necessarily mean they belong in the same book, any more than they belonged in the same college or the same classroom. Powe says they “converge on the idea of apocalypse,” but all that really means is that both looked for big answers to big questions. Mostly, they looked in different places, and they came back with different answers. Sure, we could group them as Powe does under the general heading of theorists more interested in communication than ideology. Frye himself said in an interview that he supposed his work belonged “to some extent” in the same category as Harold Innis’s and McLuhan’s theories of communication. But the term did not excite him, because communication for Frye was for dealing with the world we have, whereas literature was for imagining the world we want.

McLuhan and Frye had much in common, both the expected similarities of men of their generation and the coincidental similarity of their fame. But their differences are ultimately more meaningful. They were both professors, but McLuhan made his lectures up on the spot and never gave the same lecture twice, while Frye wrote his lectures in advance, mostly read from them in class (although he was a good enough lecturer to fool many of his students, including a young Margaret Atwood, into thinking their teacher could speak in finished paragraphs), and eventually published them. Frye followed a syllabus; McLuhan never had one. Frank Kermode called Frye “the finest prose writer among modern critics”; McLuhan thought clear writing was a sign of a weak mind. McLuhan loved collaborators, mostly as an audience; Frye thought and wrote alone. Frye read and wrote about canonical books; McLuhan read and wrote about technology, which he called media. Both were more interested in effects than causes, but Frye cared about the effects of myth on literature and McLuhan about the effects of technology on life. They were both formalists, but Frye studied form in order to reveal its content, the One Big Story we keep telling; for McLuhan, the form is the content, the medium the message.

Appreciation is fine, but Powe’s study of his teachers verges on worship. As he says, he is “still their awe-struck student.” I learned from his book, but I could have done with a little less awe, and maybe a little more skepticism about the respective weirdnesses of his teachers, like McLuhan’s numerology or Frye’s charts. For me, though I am sure not for others, Powe is too mystical a guide to these very difficult thinkers, too attracted to what I find least convincing in both, the usually hidden spiritual foundations that I try to forget in order to appreciate what they built on them. Literature was a religion for Frye, as electronic media was for McLuhan; for me, they are just human expressions.

Unless we mean a tradition of intellectuals of faith, in which case there are both Canadian precursors and examples elsewhere in the world, I am not convinced by Powe’s argument that McLuhan and Frye form an intellectual tradition. McLuhan’s Understanding Media is a much harder book to read than Frye’s Anatomy, and a much harder book to understand. It is difficult for a number of reasons, but mostly because McLuhan liked it that way, because that was his way of thinking and writing. McLuhan looked at what many people saw, and described it in words that few could understand; Frye looked at what few people saw, and described it in words that many could understand. They are both fundamentally religious thinkers, but McLuhan has the Catholic’s affection for mysteries that stay mysteries; Frye, the Protestant’s rebellious desire for answers. Frye leads you through the labyrinth; McLuhan leaves you there.

Ironically, McLuhan’s work became more widely known and has outlasted Frye everywhere except in their discipline. McLuhan predicted his victory, the defeat of the book by the sound bite, though it would be a mistake to assume he was entirely happy on or with the winning side. Frye read books. McLuhan liked books, but he read technology, and technology is with us still.

Nick Mount is a professor of English at the University of Toronto.