Before the summer of 2013, when United States National Security Agency contractor Edward Snowden leaked documents proving the U.S. government had been conducting mass surveillance on its citizens and others, the mechanics of America’s post-9/11 security architecture were almost completely opaque. Snowden’s leaks shone new light on a security architecture the government had been building in private, allowing citizens to finally scrutinize the surveillance regime they now lived under.

In Surveillance after Snowden, David Lyon, a professor at Queen’s University and head of the Surveillance Studies Centre, picks through the implications of Snowden’s revelations and what they mean for understanding the reality we now live with. He focuses first and foremost on the internet: the quintessential information technology of the modern age and the site of our most pervasive new forms of surveillance.

In a very short amount of time from its inception, the internet has become the medium in which many of us express our deepest thoughts and store our most private information. With the development of that medium, Lyon notes that many of us have just come to accept that privacy is an antiquated notion. As he writes, “social media users are now the most intensely surveilled groups in the world, and many of them paradoxically also live in democratic societies.”

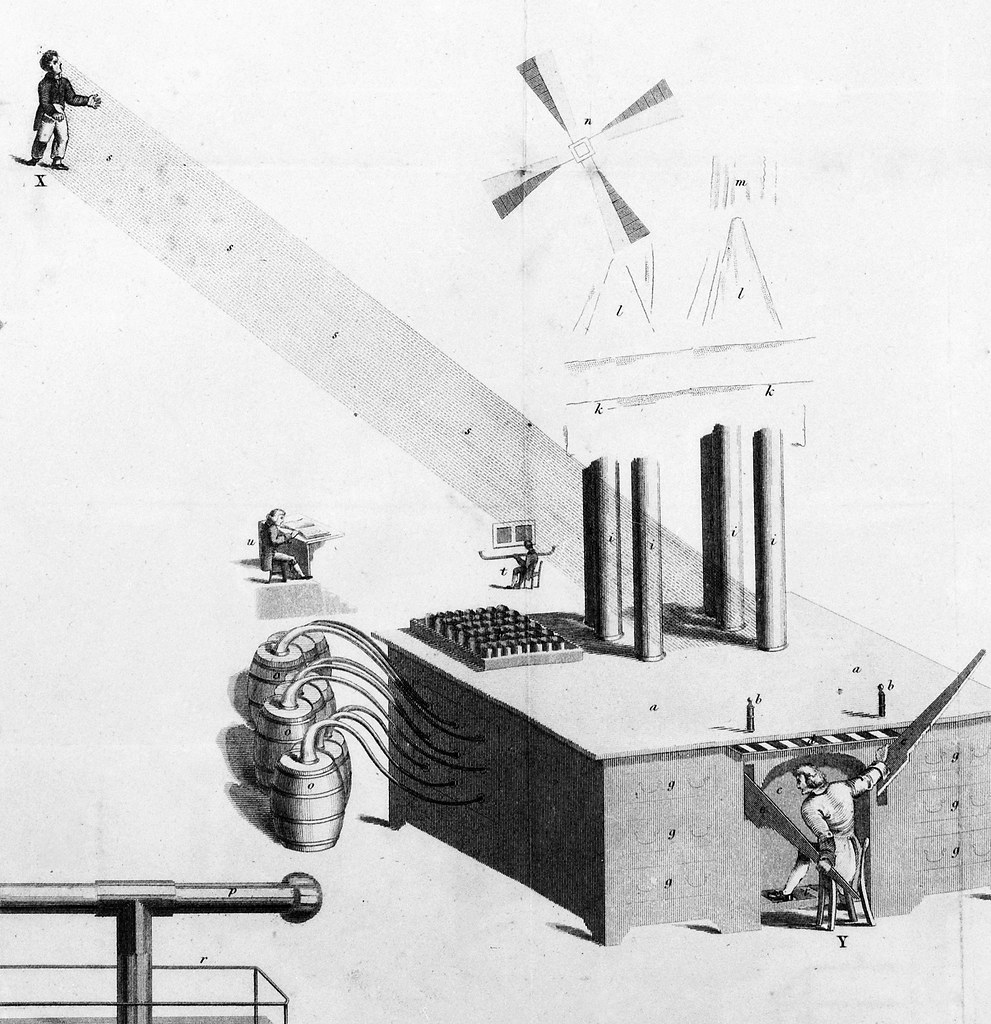

Public Domain Review

This situation came about without any public debate, but rather through the authoritarian and private decision-making process of the national security state. “‘Surveillance’ is simply not the word that they would use to describe the situation,” Lyon says about this new generation that has come of age along with the internet. “It is merely the way the internet works, the conditions of current -modernity.”

The implications of this observation are striking. If we live in a world in which our every aired thought, movement and interest are not only surveilled but also permanently documented, we have entered a period in which we have willingly and unthinkingly sacrificed our democratic freedom. Indeed, we have sacrificed much of what allows us to be human, by allowing our own private thoughts to no longer privately exist.

Like many creeping changes in society, often including those which are ultimately the most impactful, there is a sense of disbelief on the part of the populace. A sense that it cannot happen here, as Lyon notes, is one that is pervasive in democratic societies where the sense of returning to a state of authoritarianism seems unthinkable. Unfortunately, it does happen and has happened elsewhere. Following 9/11, Americans gave their national security agencies a blank cheque to do whatever they prescribed as necessary to keep the country safe.

U.S. vice-president Dick Cheney famously promised a crossing to “the dark side” in order to fight terrorism. Unaccounted for in this promise, though, was the idea that Americans would also need to sacrifice their own freedoms as part of this fight, particularly their right to privacy.

In the 1970s, following the revelation of illegal activities on the part of government agencies that culminated in the Watergate scandal, Senator Frank Church issued a stark warning to Americans about the power their government now possessed. “In the need to develop a capacity to know what potential enemies are doing, the United States government has perfected a technological capability that enables us to monitor the messages that go through the air,” Church said. “If this government ever became a tyranny, if a dictator ever took charge in this country, the technological capacity that the intelligence community has given the government could enable it to impose total tyranny.”

Church, who chaired a committee tasked with investigating Nixon-era excesses on behalf of security agencies, issued his warning in an era decades before the existence of the internet. The powers of surveillance that government agencies possessed at the time pales in comparison to those which exist today, and those which have been made possible by the vast data storage and communications possibilities provided by the internet. America may not be a tyranny today, but political currents can change (as the ascendance of political figures such as Ted Cruz and Donald Trump has shown).

Toward the end of Surveillance after Snowden, Lyon offers a number of prescriptions for activists and others to press authorities to modify abusive practices, while teaching people to protect their own privacy independently. Running through his work is a deep skepticism of the stated reason for the surveillance dragnet: the fight against terrorism. Noting that surveillance tactics have already been expanded to environmental activists and others, Lyon highlights a critical byproduct of the growth of the surveillance state: the possibility that its tools will be turned on future movements for social change unrelated to the current fight against terrorist groups.

While it is easy to imagine such tools being used in the future on a large scale against individuals rebelling against the growing income inequality in western countries as well as environmental degradation by corporate power, today surveillance is being employed mainly to target minority communities living in the West.

In 2014, as a reporter working on the Snowden documents, I published a story along with journalist Glenn Greenwald on the NSA’s systematic surveillance of activists and lawyers in the Muslim American community. One of the fundamentally underreported aspects of mass surveillance in the modern era is its racialized nature. Although many Americans were shocked that their privacy had been invaded in such a way, even in a way that did not target them directly, for people living in minority communities even more invasive forms of surveillance have long been a fact of life.

In the poor districts of American cities, often heavily populated by African Americans, Latinos and Asian immigrants, direct surveillance by law enforcement agencies has long been the norm. With the onset of the war on terror, Muslim communities also became a target, as they were infiltrated with informants and subjected to frightening “mapping” projects by agencies such as the New York Police Department’s Demographics Unit.

Following the Snowden revelations, when many of the Muslim Americans involved in our 2014 story were contacted, they barely expressed surprise at their surveillance. For them and others, the idea that their privacy would be violated by the state was expected and something to which they had long become resigned. “Surveillance after Snowden” was, for them and others, a confirmation of something they had long expected. Only the mechanics were new.

Ultimately, the book offers a brief, thoughtful and generally hopeful look at the new reality we live in. Noting that “modern societies have always been ‘information societies’,” Lyon fairly lays out the pitfalls and opportunities presented by our new hyper-charged modernity, flush with information but also a Panopticon-like level of surveillance. Although many count on government to legislate change and restrict their own powers in the face of public outcry, history has shown that this seldom occurs. In the end, individuals marshalling the powers of encryption, grassroots organizing and technological awareness will be the only thing stopping us from reaching the worst consequences of a surveillance state.

“The challenge of the Snowden revelations is to all of us, globally and at every level,” Lyon writes. “If we expect large agencies to be far more answerable for how they handle personal data, we can hardly have lower expectations of ourselves.”

Murtaza Hussain is a journalist and political commentator. His work focuses on human rights, foreign policy and cultural affairs and has appeared in The New York Times, The Guardian, The Globe and Mail, Salon and elsewhere.