They bamboozle us still. Marshall McLuhan started to write to Pierre Trudeau in April 1968, at the height of Trudeaumania. It was a unique period in electoral history: the new prime minister had become a hip sorcerer whose ability to seductively use the media seemed limitless. McLuhan was fascinated to see, right before his very eyes, someone who had instinctively hoodwinked the press and the broadcasters.

“Knowing of your acquaintance with De Tocqueville,” the professor mysteriously wrote in his first letter, “I can understand why you have such an easy understanding of the North American predicament in the new electronic age.” The rest was a mishmash of confusions and inaccuracies. When he received the note, Trudeau underlined a few phrases, including “French Canada never had a 19th century.” At the end, McLuhan observed that Trudeau had created an intimate connection to the “inner” life of the “TV generation.” Days later, McLuhan was even more exuberant, writing about “the video tape of the great debate in Toronto.” Progressive Conservative leader Robert Stanfield’s “image is that of the Yankee horsetrader.” By contrast, Trudeau’s “own image is a corporate mask, inclusive, requiring no private nuance whatever. This is your ‘cool’ TV power. Iconic, sculptural. A mask ‘puts on’ an audience. At a masquerade we are not private persons.”

Even Trudeau, largely unknown until he joined the cabinet in 1967, was dazzled at his success. He trafficked in identities: French, non-French; English, non-English; Catholic, non-Catholic; modern, non-modern; capitalist, non-capitalist; young, not-young; old, not-old; hip, non-hip; male, not-male; progressive, non-progressive. And he needed a good mask. McLuhan’s thinking was likewise enigmatic.

Trudeau finally responded personally seven months later and challenged McLuhan to think about how public policy could be affected by the power the media was increasingly assuming. “The identity process of which you speak so often is one that cannot be ignored by government,” the prime minister wrote. “I am very much aware of the sometimes search and sometimes struggle for new images in which many communities of our society are engaging. What I lack is an intuitive process to forecast for me the likeliest form of a satisfactory nature which these new images will assume. Can you help me?”

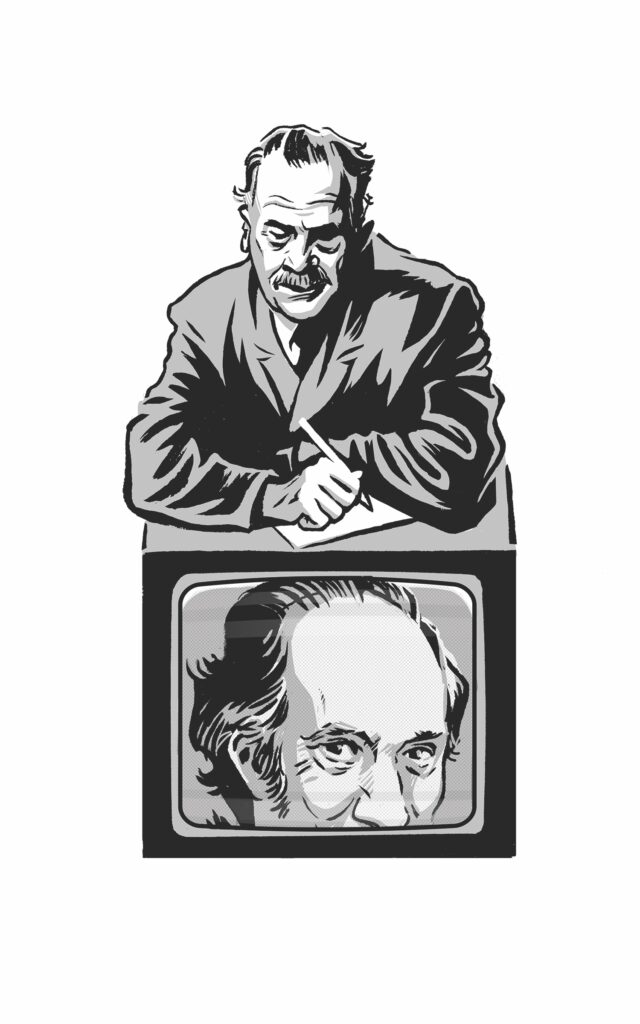

McLuhan and Trudeau, epistolary pals.

Dmitry Bondarenko

McLuhan, no policy expert, was fifty-seven, had just published his fifth book, War and Peace in the Global Village, and was now a celebrity. In many ways, though McLuhan was eight years older than Trudeau, the two rose in lockstep. McLuhan’s first book, The Mechanical Bride, from 1951, did not sell well. Most people could not understand what he was writing about or why it was important. His editors had complained bitterly about his inability to write clearly. They were correct; he felt tormented.

Eleven years later, McLuhan achieved some recognition with The Gutenberg Galaxy. It was a book for the ages: lots of short McLuhanite chapters that presented in a more accessible way how changes in technology had shaped the ideas of Western civilization in four distinct phases. As communications evolved, he observed, people knew more (and more quickly) about what was happening around them. Since television had become affordable in the early 1950s, McLuhan believed, a new intimacy had been created in the “electronic age,” as spectators felt as though they were actually “wearing” the events around them. A revolutionary “global village” had been created, and the impact of that new reality invited all sorts of new theories and speculations.

Two years later, Understanding Media shot McLuhan to superstardom. In it, he explored the idea that a medium’s key characteristics were more important than the messages it carried — almost as if technology could confer legitimacy. Television mattered so much because more people saw it than, say, read a book. McLuhan also distinguished between hot and cool: “cool” media like TV being more intimate and more persuasive, perhaps, than radio’s and cinema’s “hot” and confrontational impact. With The Medium Is the Massage, published in 1967, McLuhan deepened his views further still. And Trudeau, for McLuhan, was the masseur extraordinaire.

The University of Toronto professor urged the prime minister to adopt more conversational forums (fewer speeches, more talk), so that he could “feed forward” his ideas. Today, this may seem bold and original, but it wasn’t. Those forums were called “teach-ins,” and McLuhan thought they should be televised. He also committed himself to sending the prime minister “one-liner” jokes that could tap into the intimacy of TV (he thought “bi-lingual” and “Newfie” ones could do the trick). One-liners were useful, McLuhan insisted, because technology had so reduced the human attention span that longer narrative jokes were useless. Trudeau, not known for his sense of humour, agreed that he could use such help.

Over the course of twelve years, McLuhan sent fifty-nine letters to Trudeau or his staff. Few of them are more than a page long. Trudeau or his office responded thirty-eight times, with mostly perfunctory thanks. A third of the hundred pieces collected in Been Hoping We Might Meet Again were exchanged before the 1970s, and they were exclusively devoted to ideas on how Trudeau could connect to his audience. Issues that might well have been of interest to two corresponding Catholics — such as social justice or capital punishment — are not discussed (though McLuhan does broach abortion in 1971, comparing its “mill” to Buchenwald). There are flashes of wit and insight sprinkled through the letters, making the book useful for collectors of pithy Trudeau and McLuhan sayings. Predictably, McLuhan was told that his ideas could not be understood easily, let alone realized. In 1975, Trudeau thanked McLuhan for his insights but could not help admitting, “I find it hard to follow your thinking all the way through.”

The correspondence ended after McLuhan was cut down by an awful stroke in 1979. Trudeau was now in opposition, and McLuhan’s reputational star had fallen. The University of Toronto did not know what to do with McLuhan and his Centre for Culture and Technology, and the frustrated man dared to hope that Ottawa might intervene on his behalf. Trudeau, surprised by McLuhan’s difficulties and suddenly back in power, sent an appeal to the University of Toronto, but it did not help.

Patrice Dutil is a professor in the Department of Politics and Public Administration at Toronto Metropolitan University. He founded the Literary Review of Canada in 1991 and wrote Sir John A. Macdonald & the Apocalyptic Year 1885.